Mandy Patinkin and Kathryn Grody have been married for 45 years, and they have lived in the same Morningside Heights apartment building for nearly half that time. When I meet them down the street at one of their favorite diners on a rainy Monday afternoon in November, the two are squished next to each other in a booth, with Patinkin, 72, raving about how living in the Columbia University neighborhood makes him feel youthful. “You have all of these young people, and if you don’t look in the mirror, you’re their age,” he says. Grody, 78, disagrees. They proceed to squabble, agree to disagree, and then digress impressively — this time, into a conversation about Norman Lear and Zohran Mamdani and the failure of the Democratic Party to recognize or support the moment. About 20 extremely charming minutes later, after the two have argued over who has been speaking for longer and asked me to tally the exact time from my recording later, we get into the actual topic at hand, which is, appropriately, Patinkin and Grody’s podcast, where they do this sort of thing for roughly 45 minutes a week alongside their 38-year-old son, Gideon, who referees.

Patinkin and Grody behave at the diner the same as they do on their wildly popular TikTok and Instagram accounts; the same as they do on Seasoned, a pilot about their lives they made with Gideon and his friend Ewen Wright a few years ago that was picked up by Showtime, then dropped during the strikes, and then screened at Tribeca this year; and the same as they do on “Don’t Listen to Us.” It’s, nominally, an advice podcast for “advice skeptics and wisdom-lovers,” where listeners call or write in with questions ranging from vulnerable relationship queries to “Which animal is the rudest?” to asking Patinkin how to fix a kinked garden hose (this may have inspired his most audibly delighted answer). Patinkin and Grody describe it in an early episode as “Elder Seinfeld” — a “podcast about nothing” — and in some ways, that’s true. The structure mostly feels like a delicious excuse to allow Patinkin and Grody to be themselves, which is to say, strange and theatrical and earnest, open-hearted and funny, and unbelievably distinct, as both individuals and a couple. In an industry that sands off its participants’ edges as a matter of course, Patinkin and Grody are proudly rough and, as they put it, “unfinished.” On the show, they argue and make up, they weep, they laugh at each other and themselves, they break into improvised family songs, they tell stories both flattering and not, they allow their son to call them out. Even their ads are eccentric, with Patinkin singing joyfully about headphones for dogs and Grody getting audibly worked up as she bemoans the stigma of menopause. As they put it on the podcast, “We’ve been through some horseshit but we make each other laugh.”

You guys have spoken up about Gaza and supported Zohran Mamdani, and I’m in awe because I’ve seen some of the blowback you’ve gotten online.

Mandy Patinkin: It’s polarized in the Jewish community. We have relatives, friends, dear friends … It’s a very, very complicated time, and it’s going to be that way for a long time.

Kathryn Grody: I found this conversation very helpful, one that Hannah Einbinder does with Simone Zimmerman, a young woman who was in the documentary Israelism, about how she went from Birthright to examining her Zionism. Hannah was also raised as a serious young Zionist in L.A. That conversation is so thoughtful because she explains where she was, what she believed, and how difficult and painful it was for her to come to another conclusion.

I’ve been talking to so many people that are shocked that I supported Mamdani. Rachel, I’ve heard this for 50 years. When I was in college, wanting a two-state solution, people were calling me a self-loathing Jew. And now that there’s no room for two states —

M.P.: But there is room. I’ve been part of Peace Now forever. And now it’s called the New Jewish Narrative. And they are absolutely full speed ahead on peace. Did you see Coexistence, My Ass? See it. One story that got me in the gut was this woman from Neve Shalom, which is a community of Palestinian-Israeli people living together for years.

K.G.: For 50 years in Jerusalem.

You know, Rachel, you grow up and you always wonder, what would I have done? Would we have been part of the resistance? Would we have had the courage? To join the civil-rights movement? I went to college in ‘65, so I was too young to go to the Freedom Rides. Then you have an opportunity to really stand up.

The Times of Israel, among others, is pissed at you. Does that bother you? Embolden you?

M.P.: It clarifies my feelings. It clarifies that I believe in what I say and that I’m not intimidated by it. I know that half of the Jewish population, both in Israel and New York, agree with us and half don’t. Some of them are my family on both sides. I’m not frightened by it at all. I welcome the criticism. I feel very privileged to have the position I have, to have my speech be heard and to hear diverse opinions about what I say. I’m all for compromise, and I’m all for listening to each other and working together. I’m not for this polarized world, both in Israel and here in this country. It’s the breakdown of civility.

K.G.: I mean, that’s what social media has taught us, right? To be reactive.

Do you read the angry comments on your Instagram?

K.G.: I don’t read them. No, no. There’s some weird guy that’s got my personal email that keeps writing me criticism of my husband and I just block him. I said, “I’m sorry, you’re sadly misinformed.” Mandy gets it much more than I do. I’m very proud of him.

Let’s talk about the podcast, because that’s why we’re here. I don’t really listen to podcasts very much, but I’m loving this one genuinely.

M.P. and K.G.: Why?

M.P.: Because we don’t understand it.

[Our food arrives.]

K.G.: I’m sorry. I thought I ordered something else. I thought I was ordering the baguette with cheddar cheese. Never mind.

M.P.: So we’ll get the cheddar cheese on the side.

K.G.: No, no, it’s fine. I just thought I was ordering something else. It’s totally fine. I did this. Go ahead.

M.P.: I’m sure they would bring you a baguette.

K.G.: I’m really curious why you like the podcast.

Well, what do you think the appeal is?

K.G.: I think in this culture, you have had not one positive image of how to be older.

[The server returns.]

M.P.: She thought she was ordering —

K.G.: I thought I was ordering the baguette.

M.P.: Could she get the baguette with the cheddar cheese on the side? Thanks so much.

K.G.: It’s always pissed me off. Even since I was 50, it pissed me off. When I stopped coloring my hair — thanks to my husband, which I always give you credit, honey — I wanted to wear a brown wig and show how I was treated and then go to this hair. Because you disappear. I think during COVID, our videos were comforting and reassuring.

Did you want to do the podcast, or did you have to be convinced?

M.P.: Both of us individually and collectively have a lot of skepticism about this idea of the podcast. It wasn’t us. This isn’t our world. It’s different than our social media, it’s a mistake. And Gideon said, “Just please trust me. Just do it.” I said, “We don’t have anything to say.” He said, “You don’t ever not have anything to say.”

What I’m trying to get to is we certainly enjoy helping people in any way we can be helpful, any way imaginable. And this podcast, for whatever is happening with it, seems that it’s not harming anything. And some people like it. And so my only advice that I’ve learned so far is listen to your children. I mean, really listen to them. They know you probably better than you know each other because they have a little distance.

Are you less skeptical now? Are you glad you’ve done it?

M.P.: I’ve started to enjoy it and I am less skeptical now. And I believe Gideon. I mean, I think there’s plenty of things that we’re talking about that are boring. But it’s a nice way to spend a few hours for us. It’s a nice way to meet people who call in or say something. That’s a big deal to me, that I don’t waste the precious time of whatever life I have left. It’s a gift to do my favorite word, which James Lapine wrote in Sunday in the Park With George over and over again for my character Georges Seurat to say, which is, “Connect. Connect, George. Connect.” And if there’s anything I hope would be on my tombstone, it would be those four words.

M.P. and K.G.: “He tried to connect.”

[An elderly man approaches the table.]

Elderly Man: Mandy Patinkin. I enjoy your work.

M.P.: Thank you very much.

E.M.: You’re not retiring, are you?

M.P.: Retiring? Am I dead?

E.M.: I’m worried that we’re getting old here.

M.P.: You’re as old as you feel. How do you feel?

E.M.: Good.

M.P.: Good. That’s it.

K.G.: I think my only way of understanding this podcast thing is, it’s not predictable. It’s messy. We’re not selling anything. I mean, we are. Now we’re doing these ads. But we vetted them.

They’re so funny and weird.

M.P.: Well, I want more of them. Because that’s the thing I look forward to most.

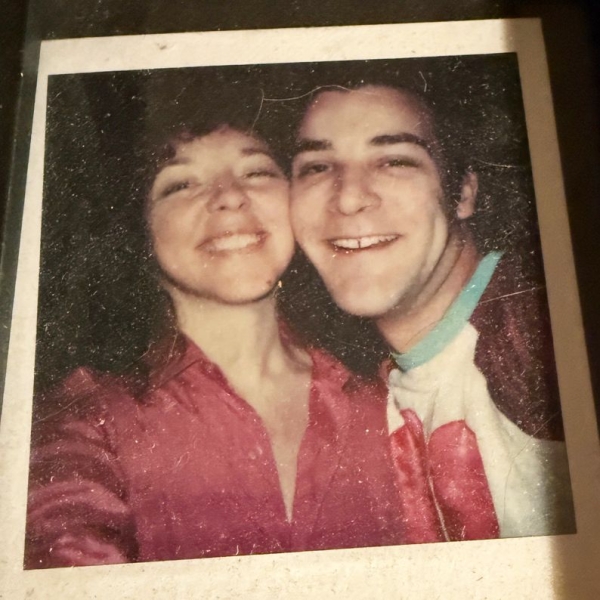

A photograph of Mandy Patinkin and Kathryn Grody in 1978, the year they met. Photo: Courtesy of Mandy Patinkin and Kathryn Grody

You look forward to recording the ads the most?

M.P.: When I’m driving, I listen to classic radio: Jack Benny, Fibber McGee, all those old shows that you never heard of. Radio was over when I grew up, but I knew Jack Benny from television, Bob Hope, all these guys who showed up in television shows. There were tons of murder mysteries on the classic radio, but there’s also all these comedy shows. And then they do the commercials. And many of them are sponsored by Jell-O. [Sings] “J-E-L-L-O!” And they’re just hilarious, the way they work it in. I’m constantly advertising Jell-O on the podcast. I’m dying for them to sponsor.

K.G.: I won’t participate in Jell-O. It’s horrible for you.

M.P.: Well, don’t say that. Now you’ve said it here. Now you’ve fucked me up.

K.G.: Sorry about it. I read an article once about how it’s made. I’ve never had it since. Anyway, I listen to way too many podcasts. And I don’t know if I’d listen to this one.

Your own? Why not?

M.P.: Well, be loyal to the title. Don’t Listen to Us. Right there for you.

K.G.: I really like finding information I don’t know about. Sean Illing has a podcast called The Gray Area. He has the most diverse array of authors and people and ideas. And he helps me. He has brilliant AI experts that are not just terrified like I am or loving it without question. He has somebody that really knows it from the beginning and that helps me be less afraid.

M.P.: And we really know nothing.

Well, that’s not true. People are asking you real questions and you guys always have great answers.

M.P.: You ask me something, I’ll have an answer. But what fascinates me is there are a lot of people in our age category and many of them have had public lives. Newscasters or writers or public people, people in business, politicians, clergy, writers. So why us? It just makes no sense to me. I just think the world has a screw loose and we’re part of the loose screw.

K.G.: I think everything’s so fast in most podcasts. You have fast reactions to what you hear from news bits. Dick Cavett used to ask a really thoughtful question and there’d be a big, huge pause while James Baldwin, of blessed frigging memory, thought about an answer. The audience wasn’t going, “Woooo!”

[Patinkin interrupts to discuss a person named Vivian and Grody looks noticeably irked.]

M.P.: Sorry, I didn’t hear you talking. You’ve been talking the whole time. I didn’t interrupt you except once.

K.G.: I have not been talking the whole time. That is absolutely untrue.

M.P.: You have, too!

K.G.: Oh my God. Rachel.

M.P.: Go play the fucking thing back.

K.G.: Rachel.

M.P.: Make the transcript and print the whole goddamn thing. You’ll see.

[The server brings Kathryn’s baguette with cheese.]

K.G.: Thank you so much.

I think there is something about the time it takes to have an actual conversation with people back and forth. It’s time. It’s not a sound bite. And it’s not predictable.

M.P.: I love you in spite of you talking the whole time.

K.G.: So delusional, honey.

I think people are desperate for community, and I think they’re desperate for comedy — is that the right word? People are hungry for human-to-human, messy contact and conversation where you’re not annihilating each other because you feel differently about a soft-boiled egg or a scrambled egg.

M.P.: And we’re no different talking to you than we are talking to each other or talking to our kids. But I will add that we are performers. So when Gideon holds up the cell phone to take a family video — originally it was for a family archive — we certainly kick into being nicer to each other. I always feel like, Let’s keep a camera on there the whole time because I get treated nicer. It’s like when I’m rehearsing a concert and I’m going over it with my piano player in my studio with just the walls and the dog asleep on the couch. We rehearse, we rehearse. But if one person comes to sit down, we perform. And it’s a whole different rehearsal and our body uses oxygen differently … I don’t remember what the question was.

Click here to preview your posts with PRO themes ››

Do you guys have things you won’t talk about?

K.G.: Well, it seems like we have no boundaries in these things, but of course we do. We probably have less boundaries about some things than other people, but we also have our own boundaries. There’s some things that are private.

Where do you draw the line on the podcast?

M.P.: We try to keep politics so far to a minimum. And I do that in my concerts as well. I need a break from it. My audience needs a break from it. I think it’s a place where people come to relax a little bit and not have to engage with constant bombardment of the profound, painful questions we’re all living with globally.

K.G.: I can talk generally about being a grandparent, but I’m not talking specifically. Not naming names. I’m protecting the privacy of my family.

Has there ever been a moment where one of you said something and the other said, “I actually don’t want that out there”?

M.P.: Yes. And we cut it. We felt safe to do and say anything on our social-media videos because Gideon was the editor and he would come in and he would be very judicious. And he has very strong opinions himself. Nothing ever went out on social media without our okay. And it’s the same with the podcast.

How has performing your dynamic over the last few years changed your actual dynamic?

K.G.: My husband likes making these videos because I’m evidently more overtly kinder in front of a camera. Everybody howls at the truth of that. I don’t particularly feel that, but it must be true.

M.P.: You didn’t think you were talking more now either.

K.G.: Rachel’s going to count the lines.

M.P.: No, she’s not, because she likes you.

K.G.: Honestly, Rachel, maybe that’s it. We’re authentic. What else can we be? We’re just who we are. And for some reason, it’s the age. It’s seeing older people that aren’t terrifying to become. You can be eccentric, you can be hideous, idiosyncratic, you can be ridiculous and still be your unique self.

M.P.: I think our behavior is asking people to not be so careful. To say what they feel and think. I think it’s the hardest thing to do: to know what you feel and think in the midst of all this noise. You really have to take a walk somewhere alone and find it in yourself. The way we behave, including Gideon, is we say what we think. We’re free.

Photo: Lemonada Media

What have been the most life-changing calls or questions for you?

M.P.: We had one call, one response that’s coming, and it was just, I was like transported to another universe. It was from Gene Kelly’s widow. It was like being with him. It was incredible. That’s all I want to say about it. The reason I bring it up partly is because we’re not interviewing famous people. We’re not interviewing great expert scientists. I think everybody’s interesting, not just famous people.

K.G.: One thing we ask is we don’t want to give medical advice. We’re not doctors.

M.P.: I played a TV doctor. I do have some advice.

K.G.: I think a lot of it is about people wanting community. I had a friend who’s a very interesting journalist. Twelve or 13 years ago, she invited ten people to come to her house in Bushwick for dinner. None of us knew each other. You couldn’t Google anybody, Rachel. You couldn’t find out shit about them. I was of course the oldest by far. There was a young guy who I became friends with. I ended up being instrumental in reconnecting him with a woman that he had asked to marry him in his 20s, broken up with twice, and ten years later felt it was the worst mistake ever. And I just saw them. They have two kids.

M.P.: They came to her play recently.

K.G.: I really hoped that the theater would have this resurgence after COVID, that people would want to gather in three dimensions. It hasn’t quite, because it’s so frigging expensive. And I think people have gotten used to being siloed in their own homes with their computer and they could tap on their screens and nobody’s seeing what their reaction is. They don’t have to be responsible to each other. And that’s a scary thing to me. We’re being trained to be AI. We gave away our signatures, being totally mesmerized by the magic, and we didn’t even realize what they were doing. We’re trying to take back agency to be human, to be odd, to be not in lockstep.

What amazes me is how good human beings can be in a crisis. There’s a hurricane, everybody works together, right? There’s a flood. There’s a disaster. Why can’t we be like that every single day, Rachel?

M.P.: Why does it take cancer to wake up and enjoy the day and see a rainbow?

K.G.: People feel better being good than hating.

M.P.: That’s what kills me — the amount of hate in this world right now. Just exhaustingly confusing. These babies that are all born, and then they grow up in a world that teaches them such pain and agony and then they go through wars that just make for generations of conflict afterwards. What do you call that when it’s in your DNA?

K.G.: Epigenetic trauma?

M.P.: Epigenetic trauma that lives on. What does it take to wake up? I don’t have the answer. What’s going on right now is so damn confusing. And honest to God, the only answer I know right now is to hold each other at night.

K.G.: The Buddhist thing about being in the present is so hard to practice. But we don’t know. I can make a plan for this afternoon. I can get hit by a car, God forbid, you know? I just believe in John Lewis’s “Practice good trouble.” Do not live in despair, and work for the better time, even though you may not see it.

Is that how you feel? You’re working for a world you won’t see?

K.G. The kind of world I want is what Joan Baez said about getting rid of flags, and we’re all one world. We do not have trillionaires or billionaires and we have nobody living in poverty. And where we’re at one with nature and we respect the Indigenous populations. That world, Rachel, I don’t think I’m going to live to see that. But I think I’m going to live to see moments that get us closer to that.

You guys had an amazing conversation on the podcast about death and dying and your differing feelings about it. Mandy, you said you weren’t afraid to die. Why not?

M.P.: I don’t remember what I said on the podcast. I have no memory of it. That’s another great thing about getting older.

K.G.: That was always true, honey, even when you were young.

You mentioned wanting to be awake and alert as your plane goes down.

M.P.: Oh, that’s right. I want my eyes open. I’ve been on a plane like that. We were in Australia. It was a killer flight, and she’s putting her nails into my thigh. She’s terrified, she’s stiff as a board. And I’m like this. [Looks both Zen and alert.] Because if this is it, I want to see that last moment. I’m praying before the oxygen’s gone or whatever. I want to see all of it.

We’ve lost too many close friends. And so we’re aware, deeply aware of time like never before. I also do another thing, which I learned from Oscar Hammerstein’s libretto of Carousel, and which is part of many different cultures. As long as there’s one person on Earth who remembers you, it isn’t over. So I say the names of everyone that my life was connected to — people that I had strong connections with, blood connections, family, and people that I barely knew, and some conflicted people in my life.

What do you think happens when we die?

M.P.: My belief in God is Einstein’s theory of relativity: that energy never dies. All of these protons and neurons, something else happens with them. They go into the ether, in the universe, and they’re there, just like light never dies. My Evangelical friends believe that everybody will be with everybody when you get there — I envy that. I don’t have that kind of belief, but I’ve created my own.

K.G.: One of the tenets of Buddhism is that all suffering comes from grasping onto that which is impermanent. I think that unconsciously speaks to a lot of people’s terror: The idea that we are the only species that are conscious about death. It makes us nuts. We cannot stand it. People like Musk think that his billions will somehow make that difference. Or these humans that are spending their entire lifetime taking supplements and getting replaced parts.

M.P.: You got a new part.

K.G.: Yeah, I did, I got a new hip I’m very proud of. It works very well.

What does being JewBu mean for you specifically?

M.P.: Yes, I am. I pray when I feed my dog twice a day. I do the healing prayer, the Mi Shebeirach, and then I do several other prayers, and she doesn’t eat until the prayer is finished and I say, “Okay.”

K.G. That’s what I think makes the most sense. Cultural stuff for Judaism, but Buddhist philosophy. You are present with somebody. This is the moment that’s fully alive.

M.P.: I remember a family bar mitzvah where one family member got up and made a speech that I never forgot. He looked at this boy and he said, “I wish for you a life of service.” And that was his definition of his existence. And he recently passed on.

[Mandy starts to cry and Kathryn holds his hand.]

I didn’t remember his speech until later, years later. I remembered. I want people to be of service to vulnerable people that are suffering, and to listen, to practice deep, deep listening, and to improve this world for the unborn.

Sorry, I lost it.

K.G.: That’s probably why I married him.

This tendency toward crying in your household is addressed in your TV pilot, as well. What’s going on with the show?

K.G.: I’m not a TV person or a movie, I’m a live-theater person. But I love working with Gideon and his creative partner, Ewen Wright, and Showtime bought it and they dropped us during the strike, but we own it all. We own the five episodes.

M.P.: The pilot plus five.

K.G.: I just want to live long enough to do those five. That’s all I want creatively, Rachel, because they are so inventive. They’re so unusual. They show people our age in situations you would not imagine, including us going to some sex club, a Plato’s Retreat–type thing. They show a whole life of a couple from beginning to end. We have it out to more people. And it was in the Tribeca Festival, it got a lot of play. I think people are wary of being creative or doing something that’s not a Marvel comic, even though I think there’s an enormous audience.

Has either of you learned something new or surprising about the other while making these projects?

K.G.: I think what’s really different and new is he has a new ability, when he loses his shit, to recover from it —

M.P.: You mean when I’m angry or emotional?

K.G.: When you’re angry, it used to take quite a long time to recover.

How long are we talking?

K.G.: Oh, a while. We have a joke in our family — “Is this a New Orleans moment?” One year —

M.P.: I just got upset, so I got in the car and I went to La Guardia and I got on the plane to go to New Orleans because I’d never been there and I don’t know what the hell was going on there. And then I get on the plane, I’m sitting in the front row, and there’s a problem on the plane. So I had a minute to calm down. They closed the door and then they opened the door. And at that moment I was like, “I think I’m okay now.” And so I said, “I have to get off the plane! I got my bag right here. I gotta get off the plane.” They said, “Sir, we had to fix something.” I said, “It’s okay. I gotta get off the plane.” And I didn’t listen to them. I just took my bag and I got off the plane. I got in a cab and I drove back to our country house.

What were you doing that whole time, Kathryn?

K.G.: We were chatting. “Dad’s in a state. He’s gone off to New Orleans.”

M.P.: So we always say now, the joke is, “Dad’s going to New Orleans.”

K.G.: He has the ability to recover much faster now and to also take responsibility for it, “Sorry, I just was volcanic in that moment.” And I’d never heard him say that in 47 years. But I’d never thought of you as volcanic. More of a hurricane blowing through, then sunshine.

M.P.: I still haven’t been to New Orleans.