Contents

The fun of Oscar season comes not just from cheering for a favorite movie. For those of us who love to be aggrieved, just as much enjoyment can be found in rooting against a certain film. When a critical mass of people on the internet all select the same nominee to dump on, that concept has a name: The movie has become an Oscar villain.

As long as there have been Oscars, there have been Oscar villains. In 1970, liberal viewers booed their TVs when known racist John Wayne won Best Actor for True Grit. Decades later, Martin Scorsese fans held grudges against “soft” films like Ordinary People and Dances With Wolves for beating Raging Bull and GoodFellas, respectively. Our modern concept of an Oscar villain is a vestige of a specific cultural moment in the late 2010s, when online cinephiles processed their Trump-era anxieties by turning one contender each year into a stand-in for the sitting president. First, it was La La Land, then Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, then Green Book, and finally Joker. This was a troubling time, and the Oscar villains offered a psychological security blanket. On a subconscious level, if those movies could be vanquished, maybe Trump could be too.

This tendency was also a product of a specific media environment, in which Twitter discourse still set the tone for the entire progressive blogosphere. Nearly a decade later, Oscar villainy no longer works the same way. The online conversation has splintered into semi-private silos like Substack, Letterboxd, and TikTok. Now renamed X, Twitter has lost its luster, while Bluesky retains the feel of those London hotels where European exiles gathered to dream of one day returning to power. You won’t find much Oscars talk there. So too have the discursive incentives changed in the second Trump term. When there’s so much explicitly fascist behavior to contend with, the thrill of calling a Best Picture nominee “implicitly fascist” has dimmed. (That’s what we have jeans commercials for.)

This year’s Oscar-villain conversation, then, is far more diffuse than ever. By my count, more than half of the 2026 Best Picture nominees have a plausible case for being the villain to somebody. Here is our annual ranking of the year’s contenders, measured by how much people on the internet are rooting against them.

Oscar Heroes

No one’s going to get annoying in your mentions for praising these ones.

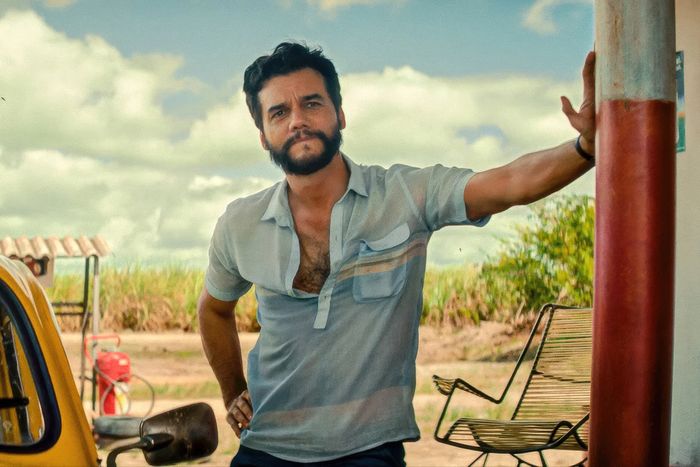

Photo: Neon/Everett Collection

The Secret Agent

Considering how awful things have been on the domestic front recently, it’s hard for a foreign-language film to become the Oscar villain, which makes it even more astounding that Emilia Pérez pulled it off so effortlessly last year. There are no such worries about The Secret Agent, a Brazilian movie that boasts pristine anti-fascist bona fides. Think of it as the South American mirror of One Battle After Another, a thriller-cum-satire about the insanity of authoritarianism and the community ties that enable us to resist it. Plus, The Secret Agent is among the least seen of the ten nominees, so rallying to its cause brings a little more cinephile cachet than the next film on this list.

Sinners

In the months since Ryan Coogler’s film became a box-office sensation, I’ve heard many people express the vague idea that Hollywood was resistant to making it. To this, I say, the studios so badly didn’t want to make Sinners that the film was the subject of a heated bidding war, which Warner Bros. won only by giving Coogler the Cadillac of director deals: final cut, first-dollar gross, and full ownership after 25 years. We should all be so hated by Hollywood! It’s true that after Sinners’s release the trades seemed to be rooting against it in a way that felt pretty racist. I don’t have any inside info, but the whisper campaign to pooh-pooh the film’s grosses could just as well have been powered by sources from rival studios (who wanted an excuse for not buying it) or within Warners itself (who wanted the people who did buy the film to get fired so they could have their jobs). It’s telling of our highly mediated moment that a handful of anonymous quotes can create a narrative that feels more real than the actual backstory. It also says something about the dynamics of social media, where “I am the only person smart enough to know that Sinners would be a hit” is an irresistible personal brand.

Perversely, Sinners breaking the overall nominations record hurts it only in this regard since it’s hard to feel like an underdog when you’ve got more nominations than Titanic. But a Best Picture showdown with One Battle After Another helps Sinners maintain its populist cred. If Paul Thomas Anderson’s film is the egghead pick, Coogler’s gets to feel like the people’s champ.

The Neutral Zone

No one’s saying much about this one, good or bad.

Photo: Netflix

Train Dreams

My parents recently watched Train Dreams on Netflix. Their review was essentially that they couldn’t imagine anyone not liking it. Now, that’s not entirely true. Earlier in the season, there was a minor controversy over whether the film’s changes to the source material — making its hero less explicitly racist and less complicit in the victimization of a Chinese laborer — sanded down the tale’s rough edges. But for every negative reaction, there were those like my colleague Roxana Hadadi’s, hailing the shift in tone from “resentment and grudge holding to melancholy and remorse.” Still, I think my parents were onto something because Train Dreams is too featherlight and gossamer thin to inspire hard feelings in any direction. The worst thing you can say about it is that it’s shot like an early-2010s Levi’s ad.

Honorable Mentions

These films all received generally favorable reviews, but they’ve also got a surprising amount of detractors, who pop up when you least expect it. Beware when discussing in mixed company.

Photo: Kasper Tuxen

One Battle After Another

The most explicitly political of the year’s major contenders is also the odds-on Best Picture front-runner, which has made OBAA discourse the season’s most inescapable topic. Most notable about the One Battle haters is not their size — they’re a small yet vocal segment — but that they can be found across the political spectrum. From the left come complaints that the film is a counterrevolutionary psyop aimed at discrediting Black activism; from the center, complaints that the film lets those same revolutionaries off the hook for their crimes against uninhabited bank offices; from the right, complaints about the implication that there may be something a little fascist about government goon squads terrorizing immigrants. Getting closer to the realm of good-faith debate are questions about whether PTA’s mock-Pynchonian wackiness is the proper tone with which to handle such incendiary material. Ultimately, most agree that having so much to chew on is what makes One Battle so great — and as scenes from the news increasingly resemble scenes from the film, the case that this is the movie of the year only grows.

Bugonia

You’d think Bugonia would have been the subject of more heated debate since its whole thing is pitting two archetypes of the modern age against each other. In one corner, the heartless girlboss; in the other, the crackpot conspiracy theorist (who just happens to be more sympathetic and charismatic than such types usually are). But as the fourth feature collaboration between Emma Stone and Yorgos Lanthimos, Bugonia has struggled against a “been there, done that” vibe all season long. Although it scored some major nominations, it enters Phase Two still feeling like a placeholder. So while a lot of people really did not like the ending, the vibe I get from them is more muted distaste than actual ire.

Sentimental Value

The king of this year’s crop of bad-dad movies, outlasting Jay Kelly and Ella McKay. I enjoyed it as much as the Oscar voters did, though, as with a lot of Joachim Trier movies, I had to check myself: Did I actually like it, or did I just want to live in the vision of bourgeois European creative life it depicts? Kick around on the cinephile internet a bit and you’ll find the sentiment plentiful. To its haters, this is the Ikea couch of Oscar movies — so tastefully Scandinavian that it puts you to sleep. (The comparison to the more lively Secret Agent, against which it’s vying for the International Film trophy, does Trier’s film no favors.) A buddy of mine noted its appeal to the industry’s divorced dads: “What if you wrote a script so good your estranged daughter had to talk to you again?”

Frankenstein

This year’s big Netflix player has me feeling like Pauline Kael: I know only one person who voted for Frankenstein. Where all the others are, I don’t know. Despite this, Guillermo del Toro’s film somehow came away with nine nominations, more than No Country for Old Men or There Will Be Blood ever got. That has made Frankenstein emblematic of what Walt Hickey calls the “Oscar chum era,” in which well-funded Best Picture contenders rack up nominations as if by default, crowding out more interesting ones up and down the ballot. However, despite del Toro’s immense personal magnetism, he missed out on the Best Director nom he once seemed likely for. That was the nomination Oscar obsessives were dreading, and without it, Frankenstein’s villain potential was diminished. And you know what? It’s pretty cool that Jacob Elordi got into Supporting Actor.

Click here to preview your posts with PRO themes ››

The Medal Places

Now we’re talking Oscar villains.

Photo: Scott Garfield/Warner Bros./Everett Collection

F1

For about 15 minutes after the Oscar nominations were announced, F1 seemed on track to become this year’s villain. How did this movie sneak into the Best Picture lineup despite clearly being not up to the same artistic standard as the others? (“The whole film’s about tires,” one member of the writing branch joked to me.) However, its defenders quickly beat back those charges. F1 didn’t knock out art-house faves like It Was Just an Accident, they argued; it beat out the other films in the blockbuster lane, movies like Avatar: Fire and Ash and Wicked: For Good. And why shouldn’t the meat-and-potatoes Academy voters enjoy a little old-fashioned star vehicle as a treat? So while it’s fun to clown on F1 as a classic boomer fantasy — a bunch of young people try to teach you something new, only to discover they need to learn from you — its lack of pomposity prevents the film from reaching the lofty heights of villainhood. I’d argue F1 isn’t the Oscar villain; it’s the Oscar punch line, which is a different thing.

Hamnet

Months ago, my colleague Joe Reid planted a flag and declared Hamnet the early favorite for this year’s Oscar villain. Its potential was of the old-school mode: It was the sensitive, handsomely mounted period piece standing between Sinners and OBAA and the Best Picture podium. It was Shakespeare in Love beating Saving Private Ryan all over again — the kind of 1999 nostalgia nobody asked for. Once it premiered, Hamnet proved one of the most polarizing contenders. Was it a devastating portrait of grief, or manipulative pablum? Soon enough, it became clear that Chloé Zhao’s film wouldn’t stand in the way of either OBAA or Sinners. Having paid its pound of flesh in the form of Paul Mescal’s Supporting Actor snub, Hamnet now looks a lot less threatening. In all likelihood, the only trophy it will win is Best Actress, and, well, if we can give that trophy to The Eyes of Tammy Faye, few will complain about giving it to Hamnet.

Marty Supreme

You know the season’s heating up when the first piece of targeted opposition research drops. Days after Marty Supreme director Josh Safdie became the most nominated individual at this year’s Oscars, “Page Six” published an article about an incident that occurred on the set of the Safdie brothers’ 2017 film Good Time, in which actor Buddy Duress exposed himself and sexually harassed a 17-year-old actress while filming a sex scene. (Duress was reportedly on drugs at the time, and the scene was not included in the finished film.) Both Safdie brothers allegedly witnessed the abuse but did not intervene. The incident was previously reported a few years ago; what is fresh about the “Page Six” post, besides the detail that Duress exposed himself, is a new framing that generally holds Josh Safdie responsible while absolving his brother, Benny, director of the far less successful The Smashing Machine. Further complicating matters: According to THR’s David Canfield, earlier this season several journalists received a mass email aggregating an unflattering Daily Mail story about Marty Supreme, leading to theories someone was mounting a Harvey Weinstein–style smear campaign against the film.

Obviously, the issue of toxic behavior on movie sets deserves to be talked about regardless of its impact on the awards race. Yet it’s clear the timing of the “Page Six” piece is one reason this story has gained more traction than earlier reports did. Just like last year’s scandal around The Brutalist’s use of generative AI, the controversy happens to turn Marty Supreme’s biggest strength into a weakness. Yes, the incident took place years earlier on the set of a completely different film. But if you’re a fan of Marty Supreme, it’s because you’re a fan of the Safdie aesthetic — the sense that the grit and chaos of New York City have been transmuted into celluloid unadulterated. The “Page Six” story shows the dark side of the Safdie magic. What used to look like freedom now looks like a noxious lack of boundaries. And it throws into new light some of the old critiques of Marty Supreme, that the movie is a little too enamored with its scumbag hero. You can put the casting of Duress, who came to Good Time fresh out of prison, right alongside Marty Supreme handing a plum role to Trump ally Kevin O’Leary.

Whether any of this affects Marty’s Oscar future is unknown. One would think Best Actor nominee Timothée Chalamet, who represents the film’s best shot at a major trophy, would be insulated from any backlash since he had nothing to do with Good Time. It brings me no joy to say this as a Marty Supreme fan, but when people spend the week after the nominations discussing your director’s possible complicity with sex crimes, you have become the season’s Oscar villain*.

*This post previously stated that Josh Safdie was removed from a Q&A session with Timothée Chalamet. He attended the event.

Three Notes on Sinners’ Record-Breaking Nomination Total

Photo: Warner Bros.

1. In the wake of Sinners breaking the nominations record, many observers noted the film’s total of 16 was made possible only by the introduction of a new Oscar for Achievement in Casting. However, I push back on the notion that Sinners benefited from an “extra” category. There are 21 feature-film categories at this year’s Oscars, just as there were from 1983 to 2020 when the Academy gave out two different Sound trophies. And indeed, two of the three films that previously held the record for most nominations in a single year, Titanic and La La Land, were able to run up their own numbers by getting nominated in both Sound categories. (Titanic won both awards; La La Land lost Sound Mixing to Hacksaw Ridge and Sound Editing to Arrival.)

2. What about the other one, All About Eve? There were actually 22 feature-film trophies up for grabs at the 1951 ceremony, but that number is a bit deceptive. Best Score was divided between musicals and dramas, and some craft categories between black-and-white and color, so there was no way a film could have been nominated for everything. I fell down a rabbit hole this week trying to figure out whether All About Eve joins Sinners in showing up in every category it was eligible for. The film doesn’t contain an original song, and it doesn’t have a story-by credit, meaning it couldn’t have been nominated in the soon-to-disappear third Screenplay category, Best Story. It does contain a credit for “special photographic effects,” but neither I nor anyone in the Academy could determine whether that meant it was technically eligible for a Best Visual Effects nom. And whether All About Eve missed in Best Actor is a complicated ontological question: George Sanders is the second-billed name in the cast and could theoretically have been nominated as a lead, but voters nominated him in Supporting instead. So I’m just going to say that, yes, Eve did get in everywhere it could have. What a feat — congratulations again to All About Eve!

3. Still, if we’re making cross-era comparisons, Sinners undoubtedly benefited from competing at a time when top-tier Best Picture contenders routinely put up numbers that would have been unthinkable a generation ago. The nomination totals were particularly juiced this year, when six different films earned eight-plus nominations. In part, that’s downstream of this being a particularly friendly season for blockbusters. But as Mark Harris noted over a decade ago, this trend really dates back to the expansion of the Best Picture category — the Academy widened the aperture of what it considered Best Picture–worthy, at the cost of shrinking the overall Oscars field. This year, a mere 15 films were nominated across the eight above-the-line categories (Picture, Director, acting, and screenplay), a number that has held steady over the past three seasons. In other words, with 35 spots available in the directing, acting, and writing categories, only five non–Best Picture nominees — Blue Moon, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, It Was Just an Accident, Song Sung Blue, and Weapons — managed to sneak through.

That’s actually an improvement from 2014, the year Harris was writing, when a mere three non-BP movies made it in (though remember, we’ve got one more Best Picture nominee than we did back then). In two ways, then, Sinners is an exemplar of our current Oscar era: It’s the kind of film the Best Picture field, and the Academy’s own membership, was expanded to let into the awards conversation. And once it was in, it did better than anyone could have imagined.

Sign up for Gold Rush

A newsletter about the perpetual Hollywood awards race.