I met Susan Brownmiller in the final minutes of the 20th century. New York had sent out its younger reporters to cover an array of parties on Millennium Eve, and I had been dispatched to hers. “It’s at her apartment — all old feminists, Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem,” a senior editor had told me. Of course, I said, I’d be game to cover it, especially because I knew that Friedan and Steinem didn’t get along. I had learned about Brownmiller, who died on May 24 at 90, through her writing — principally Against Our Will, her titanic 1975 book about the history of rape — but I knew nothing of her as a person.

When I showed up on the evening of December 31, I very soon learned that the assigning editor who’d sent me had simply made up that guest list. Neither Steinem nor Friedan was there, and I doubt either had even been invited. But Susan Brownmiller was indeed hosting, along with her friend Vivian Gornick and a couple of other second-wave elders. Susan wore a flapper dress she’d found in a vintage shop that, dripping in bugle beads and shimmer, was slightly too long — she was small, maybe five-two — because she hadn’t gotten around to having it altered. Her apartment was just the home you’d imagine for a successful writer of the 1970s: low upholstered built-in sofas, walls painted peach with sun-faded framed posters and artwork, lots of bookshelves, well-lived-in. It was a generous apartment for one person, a penthouse with a terrace wrapping around three sides; she had lived there since 1978, back when the area’s meatpackers were still active and there was a frankfurter factory down the block. The crowd was late-middle-aged, mostly academics and writers of her generation. The air was all blue cigarette haze. Susan favored Carlton, that ultra-low-tar brand that is theoretically a little less toxic than most.

Somehow, as we chatted, the subject of poker came up. Susan mentioned that she hosted a game herself. When she told this story later, she always said that I lit up (“Did you say you have a poker game?”) and all but invited myself; I remember being a lot less aggressive about it, but never mind. She was a buoyant host, and it was a good party. I talked to a few guests, took some notes, left a few minutes before midnight to hit another event, then went back to the office and filed my one-paragraph story.

As it turned out, Susan ran two poker games. One, about which the New York Times ran a feature some time later, was entirely stocked with older second-wave feminists. The other game, though, drew a much more eclectic crowd. It was composed mostly of members of EchoNYC, an early internet community that, by 2000, was a wizened elder at 10 years old. (Improbably, it still exists, though it’s smaller than it was.) That was the game Susan invited me to, and I soon fell in with its players, a unique mix of people. An IT guy might end up next to a sex-positive activist next to a corporate lawyer next to a debutante next to a curator. I was the only player who wasn’t an Echo member; access to the message boards required a non-browser arrangement that I never got around to figuring out. (Much later and through a different IRL friendship, I met and married an EchoNYC member. She doesn’t play poker.)

Susan was its ringmaster, and she clearly loved sharing her space with a lot of people. Her dining table was big enough to seat eight or so, and often the game spilled over to a second card table set up in front of the sofa. The stakes were essentially zero — nickel ante, with the pot occasionally getting up to five bucks — though you wouldn’t know it from the level of competitiveness. There was a solid amount of shit-talking, but Susan was slightly more decorous and deadpan, and therefore craftier, than most. People called for overcomplicated wild-card games, of the types that real poker nerds consider bizarre and crappy, all the time. Susan favored high-low games, where the pot was split between the holders of the highest and lowest hands, and favored the low side: She loved a hand with a nine high and I think enjoyed the perversity of throwing away a pair of aces in pursuit of a handful of nothing (which she would then bet up). She was known as Queen of the Lows, and I began to think of that strategy as a metaphor for her feminism: If the usual rules make it too hard to succeed through the conventional pipeline, maybe there’s a route in from the other end.

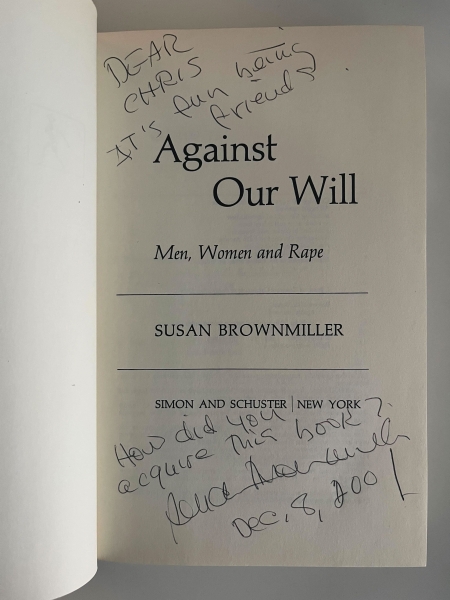

Susan was the game’s one constant; it had run for years before I joined and continued into the mid-2000s. When we learned about tournament-style poker, we tried to incorporate it into the evenings, but it somehow seemed more aggressive than the vicious, betting-for-nickels style we’d all settled into and put just enough people off that the attendance dropped. Still, I kept up with Susan. At one point during the poker years, she came to a party at my apartment, where she was the oldest guest by a couple of decades at least, and seamlessly blended with the rest of my friends. I’d told her she could smoke, but she didn’t believe me, and to suppress the urge to light up she instead had an extra glass of wine. Late in the evening, she spotted my copy of Against Our Will on the bookshelf and, when I had my back turned, added a slightly tipsy inscription.

Click here to preview your posts with PRO themes ››

It’s one of the more delightful objects I’ll ever own, mostly because the subject matter and the inscription are so very much at odds.

Years later, she spoke to me for a book project, and she told me how Against Our Will had come to be. She’d been in an encounter group with a couple of women who had been sexually assaulted. One, Sara Pines, had been raped while hitchhiking. Susan, a streetwise child of Flatbush who had occasionally hitchhiked herself, had incredulously said to her, “You were alone, and you got into a car with two guys?” (“Victim-blaming” was not yet in anyone’s vocabulary, or indeed in a lot of minds.) And then, as Susan heard other women’s stories, she recalled, “I soon figured out that Sara was a much more trusting person than I was, and that that was a big difference, and that more women were like Sara than like me.” It is easy to think of a book like hers as a product of righteousness and rage, and some of it may have been. She was not a person to filter her opinions, and even later in life, she caught a lot of flak for them. But it was also a product of empathy, a quality Susan had in generous quantities.

There’s a similar element of the unexpected to her very last book, a slim one published in 2017. It is, of all things, about growing plants, because Susan was a champion gardener on that big terrace of hers. (At one point, some building repairs required that it be covered up by scaffolding, and, true to her activist nature, she asserted her rights to a rebate for “diminished services,” applied to her ancient and already vastly below-market lease.) My High-Rise Garden is, in its way, a mini-memoir, an adjunct to her full-length one, In Our Time, a book that’s completely clear-eyed about both the successes and the misfires of her generation’s activism. The biggest of the latter was probably the anti-pornography movement, which crested around 1980, then ran out of steam. The subject came up once across the poker table, and she ruefully said that she and her fellow protesters had discovered that you simply couldn’t govern people’s psychosexual desires past a certain point. She was a realist, and she didn’t delude herself. I do wish she’d gotten to write a book she was trying to sell (and never carried off) about male promiscuity, a subject that is weirdly underexplored from a feminist perspective.

In the early 1970s, she had worked on Against Our Will at a desk in the New York Public Library’s dedicated space for authors, the Allen Room. One carrel over, Robert Caro was writing The Power Broker. He’s fond of recalling that she often took her shoes off, and that he could see her brightly colored socks poking under their shared divider. (I asked her about that period of her life once, and she said, “Oh God, he keeps telling that story about the socks!”) In the New York Historical’s exhibit right now devoted to Caro and his work, there’s a note that Susan sent him upon his big book’s publication, after Robert Moses denounced it as “venomous and vindictive.” She wrote Caro:

Dear “Venemous” [sic]:

I hereby hang up my golden gloves for attracting publicity without really trying and pass the honor on to you. And he even managed to report that the book had sex and alcohol too!

Signed,

“Impressed”

I mentioned the age difference between us before, and a big thing I noticed about the poker games — and still think about this as I get deeper into middle age — is that Susan had managed to keep together a friend group full of people so many years younger than she, one that was regularly replenished and vital. The structure of the poker nights helped, but I also put this down to a few other things. She talked to people (online and on the phone; she was a champion phoner, probably one reason she was a good reporter). And despite her tough activist spikiness — and she could be spiky; there were certainly things she could not and did not forgive — she did not hold grudges over small stuff. In Our Time stuck with me because it gets into the messy, riven, striated, conflict-saturated nature of any social movement. It’s a real antidote to the “Dems in Disarray” doomsaying we so often hear, because you realize, reading it, that every group advocating for social reform that gets anywhere is always in disarray, even when it’s in its prime. I think about it often when trying to write about history, as a reminder not to polish a narrative too smooth in search of a good story line. Signed, “Impressed.”