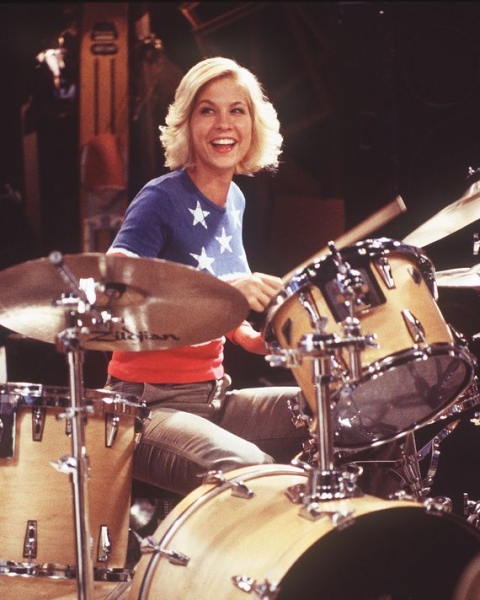

The fourth episode of Dharma & Greg’s third season, “Play Lady Play,” begins by adhering to a standard, Nashville Skyline–free sitcom formula. Dharma (Jenna Elfman) tags along to listen to a high-school friend’s band rehearsal because the drummer is out with mono. Say, she plays the drums, so why doesn’t she fill in for a few days and see if she can become the “funky backbone to this rock-and-roll beast”? The results are, indeed, funky: Snot’s Army has a solid gig debut and can play at least two songs to completion. But a few parents don’t love the idea of an adult jamming out with a bunch of 16-year-olds inside a garage, so Dharma gets kicked out of the band and takes the sticks with her. No matter. As she tells her husband, Greg (Thomas Gibson), soon after, she has the chance to audition for another group in need of a drummer. And their leader is … a man named Bob Dylan.

The ensuing three and a half minutes serve as their own stand-alone vignette, with Elfman, Dylan, T Bone Burnett, and an assembled group of musicians fooling around in a makeshift studio. Most tellingly, Dylan is the opposite of a sourpuss. He’s smiling, laughing, and cracking jokes — feeding off a radiant Elfman on the kit. It’s a confounding cameo, even for someone known to occasionally test his loyal subjects. (It was arranged because Eddie Gorodetsky, a Dharma & Greg writer, was a friend of his. Suck it, Friends.) The scene was edited down significantly from a longer filming day, with Elfman now recalling that Dylan had the final say of the episode’s cut, given the heavy emphasis on improvisation. In fact, the full tapes of Dylan’s unexpected sitcom cameo only exist in two locations: a studio vault and Elfman’s home. “It was one blip in time of a very charmed and delightful two hours of my life,” she recalls. “And it stays there in that little pocket of time as a wonderful memory.”

Dharma & Greg was at the start of its third season when this episode aired. At that point in its run, what was the perception of your show compared to other sitcoms scattered across the networks?

It’s funny, I never viewed it in terms of other sitcoms that were out there, because it was such a unique experience of getting it. The show was created for me. I was getting presented with a lot of ideas in the mid-’90s. The first guys I met with were like, “We’d love to create a show for you, but we’re busy this season. We’d have to wait until next season.” And I said, “I’ve got momentum, I’m going on to the next person. So, no, but thank you.” Then I heard from Chuck Lorre, who had become aware of my work from my first sitcom, Townies. I had lunch with him and Dottie Zicklin. They pitched me the general idea of Dharma & Greg. They had this concept of a character who, when you scratch the surface of her, you don’t get a different beast — you just get more of her. I really understood what they meant, and I shook hands on it. I said, “Let’s do it.” I didn’t go talk to my agents and didn’t go ask for anyone’s opinion. I knew it was going to be a hit.

I was very fresh on the scene, just so grateful and enthusiastic to be there. They wrote to my strengths. I didn’t ever look at the ratings, truly. I was told what the ratings were, but I didn’t care. I didn’t sit there doing an analysis of the competition. I was there every week, having a great time. I know it sounds naïve, but I didn’t put my attention on things that were out of my control. But season three was definitely the peak of its success.

There weren’t any set lines or pages of script. We didn’t have actual dialogue that was ‘written.’ We sat down and they filmed us for two hours.

So it’s fitting that Bob showed up during this successful period. How exactly did he get into the orbit of the show?

I always wanted to play drums. I wasn’t raised with a lot of money, so we didn’t have extra funds for a drum kit. One day I realized, Wait, I can afford a drum kit now. This doesn’t have to be some fantasy tucked away. I can start drumming if I want. So my husband bought me a drum kit for Christmas that year and I started learning. I told the writers, “I’m starting to learn to play drums. If you want to build that in anywhere, feel free.” We had previously done one episode where Dharma plays drums with a high-school kid in his band. Eddie Gorodetsky, one of our writers who had deep music ties and a giant album collection, came in and said, “Bob Dylan is going to appear in the show and we’re going to create a thing where you audition for Bob’s band.” Eddie has so many friendships in the music industry. I was like, “Is that a joke? That’s amazing.” They had a silent electric drum kit in my trailer that I practiced on, and then I had another one I filmed with.

Prior to his cameo, if someone said the name “Bob Dylan” to you, what response would that have elicited?

I was a huge fan of his music. There’s this one song of his from a more obscure album, Planet Waves, called “Wedding Song,” and it’s one of my all-time favorites. There are bigger Bob Dylan fans, obviously, who know every song from every album and all of his history. But I was a solid Bob fan when I met him. I was very struck when we met, because I know everything he has been through. I think I was expecting a tired fellow, because I knew this guy had experienced a lot of a loss, trauma, and challenges. I thought he was going to be rough around the edges. But what really struck me in the hair and makeup room beforehand was this childlike glow and sparkle in his eyes and curiosity about life and others.

Click here to preview your posts with PRO themes ››

That’s such a lovely surprise. What was your opening line to him to break the ice?

I was very shy. They set up the entire stage before Bob arrived to ensure we were economical time-wise. I wanted to be respectful. I just didn’t know what to expect. I think I assumed the worst so I wouldn’t be let down or surprised if I met someone who was shut down. So he came over and said, “Hi, I’m Bob.” And I said, “Well, I know, and I’m very glad you’re here. Thank you so much for doing this.” He proceeded to be complimentary. He asked me some questions about myself and was curious about how I got good at comedy. He was very interested and sparkly-eyed, like a curious young boy. People who’ve been through a lot of trauma tend to lose that outlook, and he hadn’t lost it. That startled me. I thought it was beautiful.

What were the creative parameters set up for his scene? Was it always visualized as this extended jam?

If this scene happened nowadays, I would have a little bit more ownership over myself because I’m not fearful of anything anymore. But at the time, I was more intimidated by things and didn’t feel a full ownership of myself in many spaces that I went into. So they said, “We’re all set up. We’re just going to film. Do your thing!” It was just improv, really. There weren’t any set lines or pages of script. We didn’t have actual dialogue that was “written.” We sat down and they filmed us for two hours. I improvised with him and they pieced it together afterwards.

I had never played drums outside of my own house or played with another musician before. I didn’t know anything, and it’s probably good that I didn’t, because I did enter it with a very unserious and playful attitude. I didn’t take myself seriously as any musician with big goals. So I wasn’t intimidated by playing with these wonderful musicians. Still, it was a heightened experience. We were all dumbfounded that we actually had Bob Dylan on the stage. What seemed expressed was, “I’m coming in, I’m sitting down, I’m playing, I’m leaving.” Not hostile, just efficient.

You got a full-teeth smile from him. You had the magic touch that day.

I made him giggle on-camera! He knew that he wasn’t in a musician’s turf, but in a sitcom turf. He knew he was in my home and I knew, musically, I was in his home. We both had respect for the mastery of the other person. So we were amused at the situation. He granted me the right to drive the scene comedically. He was very kind and gentle in making me sound a bajillion times better than I was with how he played his guitar. I’m a huge Traveling Wilburys fan, and if you listen to the music that’s coming out of us, some of those are Traveling Wilburys–ish.

“We were all dumbfounded that we actually had Bob Dylan on the stage.” Photo: ABC Photo Archives/ABC

You’ve now got me thinking about what was in that additional one hour and 57 minutes of footage.

I’ll tell you a little gem. Bob’s contract, apparently, stipulated that all the footage had to stay in the vaults of 20th Century Fox Studios, which produced the show for ABC. He approved the final cut. The rest of the tapes couldn’t be used, shown, or go anywhere. Eddie asked Bob — because they’re friends — a few weeks after we filmed the episode, “For Jenna’s birthday, can she have all the footage?” And Bob said, “Yes.” So I have a copy of all two hours. I haven’t watched it recently. I have to have it transferred onto something that’s not an eight-track VHS tape.

Do you feel this cameo helped the show in any way, either in terms of exposure or giving it a boost amid the crowded television landscape?

I have no idea what the chatter was afterwards. But I do have to say, I don’t think there are many sitcoms that have moments where a legend comes on and actually plays music with the actor. That’s very rare. To me, it fits perfectly with everything that was unique about Dharma & Greg that hadn’t been seen on television in a long time — the energy of Dharma as a joyful, funny, energetic, and positive female character. So having Bob Dylan come on, and actually play music, fit into all of the unique specialness that was our show. Listen, I love Frasier. I love Friends. I love Seinfeld. But what I loved about Dharma & Greg was it was wrapped in a big bow of joy. We didn’t lean into neuroses. It wasn’t about being neurotic from what’s happening in your life. It was about the joy and humor of different people trying to get along, all anchored by someone who’s a positive force. Having Bob Dylan come on is exactly the sense of awe and wonder in how Dharma lived.