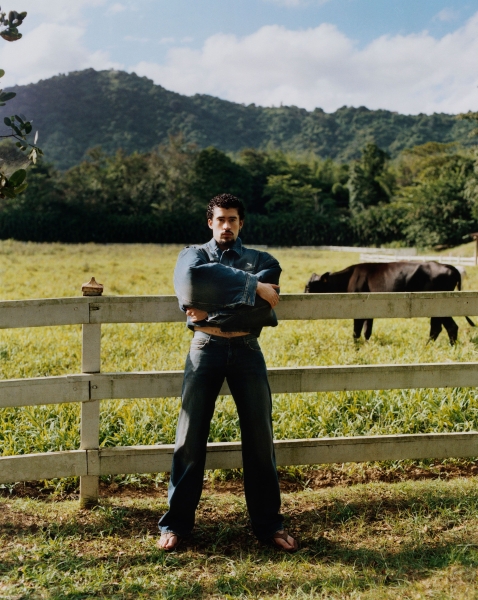

LOEWE Viscose Shirt, Cotton and Wool Draped Trousers, and Shiny Calf Crown Oxford, at loewe.com. CARTIER Santos de Cartier Necklace in 18K white gold and steel and Juste un Clou Earrings in 18K white gold, at cartier.com (worn throughout).

Lea este artículo en español.

Before he was Bad Bunny, when Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio was still only Benito, named after his father, who was named after his father, growing up in a barrio called Almirante Sur in Vega Baja, about a 45-minute drive from San Juan depending on how good you are with potholes, he didn’t know much about Puerto Rico’s history. In school, he was taught that Christopher Columbus “discovered” the island; that Juan Ponce de León was its first governor, appointed by the Spanish Crown 4,000 miles away; and that Luis Muñoz Marín, the namesake of the big airport, became Puerto Rico’s first democratically elected governor in 1948.

“That’s basically 500 years in between of history that they don’t teach us,” he says. We’re sitting inside the claustrophobic back office of the Arthur Murray dance studio in Miramar, a San Juan neighborhood, a few days before Christmas. He’s between takes of his music video for “BAILE INoLVIDABLE,” an unexpectedly straight salsa track off his sixth studio album, which would be released two weeks later. The dark-wood-paneled room, its walls lined with VHS tapes, cassettes, and CDs, looks like it’s stuck in 1994. He’s still in the slightly wrinkled gray sweat suit he wore for filming, a gold chain with a teeny machete-shaped pendant around his neck. “They don’t talk about all the gringo governors that stole us just like Spain did,” he continues. “And all the gringo governors that killed Puerto Ricans, same as Spain fucking killed Taínos.”

In This Issue

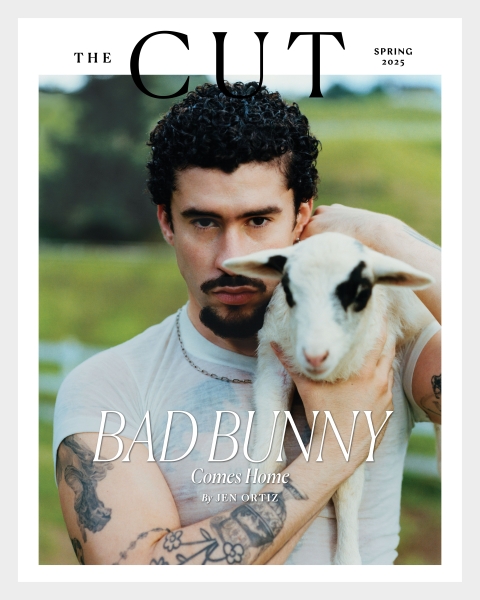

Bad Bunny Comes Home

See All

As Juan González writes in his doorstopper Harvest of Empire: A History of Latinos in America, “Few children in the public schools, including Puerto Rican children, are taught anything about Puerto Rico except for its geological location and the fact that it ‘belongs’ to the United States” — that the island is “como un hijito de Estados Unidos” (like a little child of the United States), Benito says, sitting up in the swivel desk chair and outlining the shape of the mainland in the air with his fingers. We speak in a mix of Spanish and English — he mostly the former, I mostly the latter — after I convince him that “entiendo casí todo, really” (I understand almost everything), having grown up in Spanish Harlem with a dad from the south side of the island and a mom from the Dominican Republic. I want to hear him think, process, reflect without the self-editing of translation. While Benito’s English, as he told Jimmy Fallon on The Tonight Show in January, has gotten better, his words flow faster, fuller, more cabrón in his mother tongue.

Benito, now 30, has been teaching himself the lessons he never received, “reading, watching things, listening to songs — because you can learn through the songs, too.” He’s not done, just taking it step-by-step, he says: “I want to learn every day more.” Technically, this education began much earlier, when he was a child overhearing the local news on his parents’ television. “Viendo cómo este gobierno acusaban a fulano, fulano y ‘corrupción,’ ‘corrupción’ ” (Seeing how this government accused this one, that one and “corruption,” “corruption”), he says of the headlines that would flash across the screen. Benito is part of what Mayra Vélez Serrano, a professor at the University of Puerto Rico at Río Piedras, has termed “the Crisis Generation”: Born in the ’90s and early aughts, Puerto Ricans Benito’s age and younger have grown up under successive political, fiscal, or climate disasters with little break in between. As he puts it, they have spent their entire lives surviving “otra etapa de lo que es la colonización” (another stage of colonization).

Sometimes distance can make clear what immersion obscures. Last year was the longest he’d spent away from the island. In the first half, he was on the road for a North American tour promoting his most recent album, Nadie Sabe Lo Que Va a Pasar Mañana, a braggadocian return to Latin trap that earned him yet another Latin Grammy and $208 million in ticket sales. In May, he co-chaired the Met Gala, and the following month he flew to Paris to perform in the Place Vendôme for Vogue World. In the fall, he spent time in New York, shooting scenes for Darren Aronofsky’s upcoming film Caught Stealing, and in New Jersey, where he appeared in a cameo alongside Adam Sandler in Happy Gilmore 2.

“Cabrón, este año para mí ha sido largo y ha tenido demasiadas partes” (Bro, this year has been long for me and has had too many parts), he says, staring down at the floor as though trying to recall it all. “Yo tuve una gira, tuve tres novia, tuve tres hijos … No tuve tres hijos” (I had a tour, I had three girlfriends, I had three children … I didn’t have three children), he says jokingly, sending his publicist’s head shooting up from her phone in a mild panic.

The longer he’s been away, the more he has come to understand something any diasporic Boricua knows all too well: There’s always some part of you that’s en la isla even if you’re not. “No importa en qué parte del mundo esté, puertorriqueños que llevan años fuera de Puerto Rico, como tu papá, duermen en ese lugar pero viven en Puerto Rico” (It doesn’t matter where in the world you are, Puerto Ricans who have been away from Puerto Rico for years, like your dad, sleep where they are but live in Puerto Rico).

It’s also why he has spent the past 12 months getting back to the island through his new album, DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS, a triumphant parade across 5,325 square miles and thousands of years of history. And it’s why, for the time being at least, he isn’t going anywhere. As he declares on the album’s outro:

“De aquí nadie me saca, de aquí yo no me muevo / Dile que esta es mi casa donde nació mi abuelo / Yo soy de P fuckin’ R.”

(Nobody’s getting me out of here, I’m not moving from here / Tell him this is my house where my grandfather was born / I’m from P fuckin’ R.)

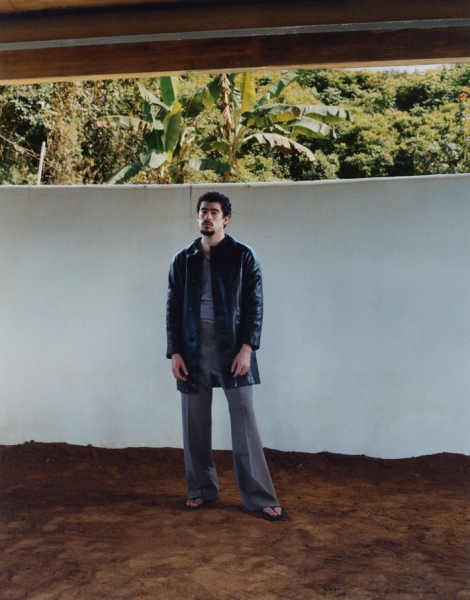

PRADA Coat, Knitwear, and Trousers, at prada.com. CARTIER Necklace and Earrings, at cartier.com. THE SOCIETY ARCHIVE Men’s Brazil-Logo Flip-flop, available upon request.

A few weeks earlier, on a Monday morning, Benito wakes up at home — finally, after three consecutive months away. At the farm where we meet, the low hum of salsa music is coming from some nearby speakers, occasionally interrupted by the nearby click-clack of his friends crashing dominoes on a plastic table, as the savory-sour smell of garlic and red onions in a hot pan emanates from the kitchen. In a pair of blue Adidas chanclas and his inside-the-house clothes — an untied pair of satin Bode gym shorts and a Tito Trinidad T-shirt — he shuffles around, slowly getting ready for the day, still bleary-eyed behind his Celine sunglasses.

The air is thick with humidity, the scent of damp grass, and the croaks of coquis, Puerto Rico’s native frogs. The sprawling property is surrounded by transcendent mountain views. It’s mountains like these that Benito had in mind when he began DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS. He had been thinking about the ongoing gentrification and privatization of the island’s beaches — beaches that look, Benito tells me in scare quotes, “totalmente conquistadas” (totally conquered). Though the beaches — as in all the land that the water touches at the highest tide — are legally required to be accessible to the public, luxury development often encroaches on the shoreline, either with new construction or by erecting obstacles like gates. “¿Y qué tal si un día ya tienen todas las playas?” (And what if one day they have all the beaches?), he says. “Lo único que va a quedar es el monte y van a querer también coger el monte y la montaña” (The only thing that will be left is the forest, and they’ll want to take the forest and the mountain too).

He pictures his fellow Boricuas retreating farther toward the center of the island as more and more land is bought out from under them. Until we’re all like this, he says, wrapping his arms around himself and shrinking back in his seat. That’s where he wants to take us on this album, he says: “para el centro, para el monte” (inside, to the mountain).

That image, of his Puerto Ricans both stranded and trapped, has kept him up at night. “Esto fue un sueño que yo tuve” (This was a dream I had), he says at the top of his haunting bolero “LO QUE LE PASÓ A HAWAii,” the 14th track on DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS. The song is an elegiac plea that the cultural erasure that happened in Hawaii doesn’t happen to his home. Against a synth bass, the sparse strings of música jíbara, and the background calls of coquis and a crowing rooster, his voice is as heavy and languorous as the island’s weather: “Quieren quitarme el río y también la playa / Quieren al barrio mío y que abuelita se vaya” (They want to take away my river and also my beach / They want my neighborhood and for Grandma to leave).

“When he expressed the concept,” MAG, the producer of Un Verano Sin Ti and much of DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS, tells me, “it felt daunting because it’s like we’re trying to execute this very deep song that he already had written but didn’t have music to. I remember we brought in all these musicians and he told the guy that was playing the güiro, ‘I want you to play like you’re the last Puerto Rican standing on the island.’ And if you hear the very end of the song, he expressed that in his playing, because the last thing you hear is the güiro and it kind of dies down. If I listen to it now, it still makes my eyes watery.”

The album, Benito says, has reconnected him with who he really is, his interior self, including the parts of him shaped by the island’s political turmoil. Benito was born a year into Governor Pedro Rosselló’s scandal-plagued administration, the same year Rosselló began privatizing Puerto Rico’s health system and public hospitals, burdening Boricuas who couldn’t afford private insurance. Years of economic uncertainty, austerity, recession, and more privatization followed. Puerto Rico’s debts piled up as successive governors failed to find stability. Then came the “vulture funds,” which purchased those debts at a discount, knowing that because of a 1984 bankruptcy law passed by U.S. Congress and the island’s Constitution, Puerto Rico would be forced to pay them back. Every U.S. president seemed to further tighten the screws. President Obama, for his part, signed the PROMESA bill, creating a financial-oversight board, known to many Puerto Ricans as La Junta, to deal with those debts, leading to more austerity measures, including the closure of more than 400 schools.

Benito was then in college at the University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo, working as a bagger at an Econo supermarket on the side when he wasn’t uploading songs to SoundCloud. The year after his Latin-trap track “Diles” earned him a record deal and his first taste of celebrity, La Junta proposed cutting the entire university system’s budget by a third. That same year, Hurricane Maria made landfall, killing thousands and causing $90 billion in damage. People went without power, potable water, and cell service for months while President Trump tossed out paper towels in a crowd. Benito’s parents, he told the New York Times in 2020, didn’t have power for months. By the time members of the administration of Governor Ricardo Rosselló, Pedro’s son, were arrested on corruption charges in 2019 — a scandal eclipsed by another when homophobic and sexist group-chat messages by Ricardo and members of his administration were leaked — the people had had enough. For days, thousands poured into the streets of San Juan until the governor finally resigned.

By that point, Benito was already collaborating with people like Cardi B and Drake. His debut studio album, X 100PRE, was released seven months before the protests and landed him on Billboard’s “Top Latin Albums” list. When the scandals broke, he was headlining a tour that would take him across North America, Europe, and Latin America. He was in Ibiza when he postponed his European tour dates to fly back and join the protests. After Ricardo’s resignation, Benito, in a flamingo-pink sweat suit, addressed the crowds while waving over his head the Puerto Rican flag — the one with the azul clarito (light-blue) triangle, originally designed by pro-independence Puerto Rican exiles in 1895 in New York City and still associated with the pro-independence movement. “Puerto Rico no se va dejar” (Puerto Rico won’t let itself be fucked with), he said into the mic, closing his eyes. “Bienvenido a la generación de Yo No Me Dejo. Los quiero, Puerto Rico” (To the “You Can’t Fuck With Us” generation, welcome. Puerto Rico, I love you).

Participating in those demonstrations seemed to be a political awakening for Benito — he later told Rolling Stone that he thought, Why hadn’t I done this before? — but eventually, the albums and tours and extracurriculars, including a stint in the professional-wrestling ring and a cameo in a Brad Pitt movie, grew more demanding, and he found himself farther and farther from the island.

In 2023, a year after releasing and touring Un Verano Sin Ti, which earned him both a Grammy and a gig headlining Coachella, a first for a Latino solo artist, he temporarily relocated to Los Angeles. His life was an escapist L.A. fantasy: He had a house in the Hollywood Hills; he sat courtside at Lakers games; he was rumored to be double-dating with Hailey and Justin Bieber with his on-again, off-again girlfriend, Kendall Jenner, a supermodel and a Kardashian. When Benito and Jenner debuted a Gucci campaign together that September — paparazzi-style photos of them moving through an airport with their matching logomania carry-ons — the internet worried this was less of a break and more of a permanent relocation. As one viral tweet put it, “He’s not Benito anymore that’s Ben 💔.” The following month, he dropped Nadie Sabe Lo Que Va a Pasar Mañana, filled with tracks about partying with Leonardo DiCaprio in Monaco, not settling down, and fucking inside, yes, the Gucci store.

In reality, he swears he’d never missed Puerto Rico more. “Me hacía demasiada falta” (I missed it too much), he says. “Y yo pensaba, Bro, esto fue decisión mía, porque necesitaba un tiempo para mí mismo. Ahí comencé a empatizar un poquito más con las personas que se van sin querer. Como que las personas que tienen que tomar la decisión difícil por su familia, el futuro de sus hijos, de ellos mismos. Y ese aspecto me dolía” (And I thought, Bro, this was my decision, because I needed some time for myself. That’s when I began empathizing more with people who leave without wanting to. Like, people who have to make that difficult decision for their family, for their children’s future, for themselves. And that thought hurt).

He returned to Puerto Rico at the start of last year, and while partying in disguise at La SanSe, a mid-January festival in Old San Juan that caps off the island’s extra-long holiday season, he started working in earnest on what would become DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS.

It’s his first album of his 30s, and with a new decade comes new preoccupations. He’s an uncle now; his friends and family are having kids; he’s thinking seriously about the future — his and Puerto Rico’s and how to keep the two intertwined. Holding on to Puerto Rico, his Puerto Rico, is a running refrain throughout DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS, including in a surprise 13-minute film Benito dropped on YouTube two days before the album’s release, starring Jacobo Morales, the influential 90-year-old Puerto Rican director, actor, and poet whose 1989 Lo Que le Pasó a Santiago remains the only Puerto Rican film to be nominated for an Oscar. The video, which Benito co-directed and co-wrote, follows Morales, who, after reminiscing over photos at home, heads out to the local panadería. The walk is lined with English-speaking neighbors either eyeing him suspiciously or ignoring him entirely, and the bakery has undergone a glossy venture-capital makeover: the Blank Street Coffee treatment. Even worse, the gringa at the counter doesn’t know what queso de papa (cheddar cheese) is and offers up “vegan quesitos” before realizing they’re sold out.

As the 25,000 or so comments will tell you, the gut-punch comes around the seven-minute mark, when, after trying to pay the overpriced bill in cash, Morales is informed the business is newly cashless per “corporate policy.” He asks if he can just pay later; when the cashier says “no,” he tries again: “But please. I knew the original owner.” A dejected Morales shakily readies himself to leave when a Puerto Rican guy at the nearby counter stands up and taps his card to pay for him. “Seguimos aquí” (We’re still here), he tells Morales.

That specter of displacement has been terrorizing Puerto Rico for way longer than Benito has been around. In 1915, Arthur Yager, President Wilson’s appointed governor of Puerto Rico, wrote of the “wretchedness and poverty among the masses” and reasoned that “the only really effective remedy is the transfer of large numbers of Porto Ricans [sic] to some other region.” In 1931, Dr. Cornelius P. Rhoads, an oncologist working in San Juan, wrote that Puerto Ricans were “beyond doubt the dirtiest, laziest, most degenerate, and thievish race of men … What the island needs is not public-health work but a tidal wave or something to totally exterminate the population.” He went on to boast of killing eight patients and “transplanting cancer into several more.” Eighty-eight years later, in those leaked group-chat messages between Governor Rosselló and his cronies, Edwin Miranda, a publicist working for the administration, wrote, “I saw the future … is so wonderful … there are no Puerto Ricans.”

On a drive from Isla Verde to Santurce during one trip to Puerto Rico, I noticed black-and-white graffiti on a stretch of highway spelling out in big block letters WE SEE OUR FUTURE: IT’S FREE OF COLONIZERS.

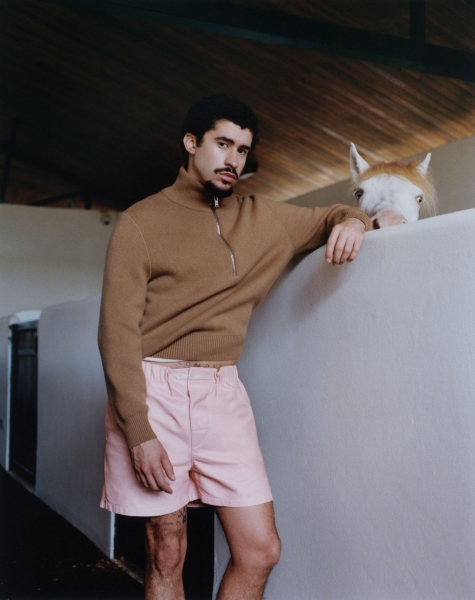

BOTTEGA VENETA Sweater and Shorts, at bottegaveneta.com. CARTIER Necklace and Earrings, at cartier.com.

In interviews, Benito has often said, as one way of explaining his sound and his refusal to “cross over” by rapping or singing in English, that he makes music for Puerto Ricans, but “this project especially is the most.” The majority of the album’s 17 tracks were recorded at home and around the island, in Río Piedras and in San Juan, and incorporate, as he puts it, “música puertorriqueña — la música y la cultura de Puerto Rico de los últimos 50 años” (Puerto Rican music — the music and culture of Puerto Rico of the past 50 years). It’s music born out of the instrument collection I’d seen strewn around the oversize couches in his living room during a visit: bombas, timbales, maracas, a keyboard, a cuatro guitar.

The result is both an homage and a proclamation, a planting of a flag. Bomba, plena, salsa, música jíbara, house, and reggaeton — the music, he says, he’s been listening to since he was a kid — all blend together with his languid, low-pitched delivery. The older, traditional genres of Puerto Rican music are rooted in storytelling, their rhythms and lyrical styles a way of documenting history and passing it along. The percussion of bomba dates back to the 1500s, developed by enslaved Africans who had been forced to the island by Spaniards to work the sugar plantations; the drumming was used to communicate and commune with one another. From bomba came plena, “the newspaper of the people,” around the early 1900s, which filled out the sound with more instrumentation and lyrics addressing current events. Finally, música jíbara came from the Puerto Rican countryside, soundtracking, like American country music, the everyday experiences of everyday people.

Click here to preview your posts with PRO themes ››

“I feel like Benito found his purpose as an artist through this album, and I think you can hear that,” MAG tells me. “And Benito put all eyes on Puerto Rico through an album.”

In “NUEVAYoL,” he speeds up “Un Verano en Nueva York,” by El Gran Combo de Puerto Rico, against the deep bass and fast percussion of dembow, rapping over it to transform the leisurely 1975 salsa classic into a bop. There’s reggaeton throughout, like “KETU TeCRÉ,” a salty breakup track made for the club, and “EoO,” a dance-infused throwback that will have you wondering if your knees can perrear (Google it, coño) like they used to. “CAFé CON RON,” an ode to getting drunk and waking up hung-over, featuring the band Los Pleneros de la Cresta, combines bomba’s drumming with plena’s scraping güiro and call-and-response. And in “BAILE INoLVIDABLE,” Benito pushes his voice to hold court with the salseros he grew up listening to. In every detail, Benito made the album a tribute to his home: The live instrumentation, for instance, was provided by students of Escuela Libre de Música de San Juan Ernesto Ramos Antonini and Escuela Pablo Casals in Bayamón, two public music schools, with features from RaiNao and the band Chuwi — all young Puerto Rican artists.

“Se siente de momento como que protegiendo mi música, la esencia de lo que es todo” (It feels like I’m protecting my music, the essence of what everything is), Benito says. “Es algo que es parte de mí — no porque soy Bad Bunny sino porque soy Benito” (It’s something that’s part of me — not because I’m Bad Bunny but because I’m Benito).

It was the same impulse that led him to get involved in this past fall’s gubernatorial election in Puerto Rico. In September, Benito purchased billboards across San Juan that described a vote for PNP — the incumbent party whose candidate, Jenniffer González-Colón, is a pro-Trump Republican and a former running mate of Ricardo Rosselló’s — as a vote for corruption and a vote against Puerto Rico. Over Labor Day, he sat down for an emotional 90-minute interview with a popular local YouTuber, El Tony, to encourage new-voter registration, especially among young people, and stressed that he wasn’t there as a celebrity but as someone who wants to be able to live forever — and to one day raise his kids — in Puerto Rico.

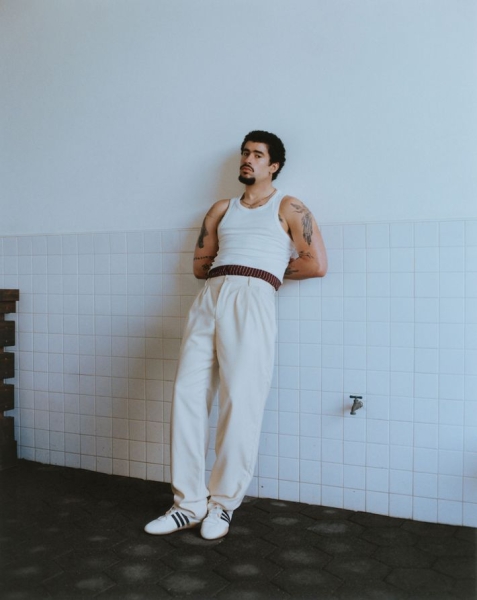

SAINT LAURENT by Anthony Vaccarello Boxers and Pants, at ysl.com. CALVIN KLEIN Cotton Classic Tank Top, at calvinklein.com. CARTIER Necklace and Earrings, at cartier.com. ADIDAS ORIGINALS Bad Bunny Ballerina, at adidas.com/badbunny.com.

Then in November, pushing down the nerves he feels when he’s not performing as Bad Bunny, Benito gave a 20-minute speech at a rally in San Juan for La Alianza, the progressive reform-seeking third party. Benito told the massive crowd about his dreams for a Puerto Rico free of corruption, free of structural abuses, and free of lying politicians who have lost respect for their people: “¿Y ustedes ya saben qué? Yo soy Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, soy puertorriqueño y siempre cumplo mis sueños” (And you know what? I’m Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, I’m Puerto Rican, and I always make my dreams come true). Not this time, though. González-Colón won, but it wasn’t a total loss: La Alianza’s candidate, Juan Dalmau, came in second with more than 390,000 votes — something a third party in Puerto Rico, let alone a pro-independence candidate, has never done.

By then, Benito was far into the album. When it came time to start releasing his new music, he decided to turn the YouTube visualizations for the album’s tracks into mini history lessons styled to look like classroom PowerPoint slides and written by Jorell Meléndez-Badillo, a historian at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and the author of Puerto Rico: A National History. Benito says he knew from the beginning that he wanted to find a way to incorporate “the basic history of Puerto Rico,” which “se desconoce mucho a pesar de que es básica” (is very unknown even though it’s basic).

The Instagram DM came from a member of Benito’s team while Meléndez-Badillo was on vacation in Portugal with his family. “I am sort of a workaholic,” the professor tells me, “so I had promised my wife, my kid, my therapist, and everyone else that I was leaving my computer behind.” Luckily, his wife and child, like Meléndez-Badillo, are Bad Bunny fans and understood, as he says, “what was at stake. I was like, ‘I have to say yes.’ ” He spent the next week trading messages with Benito’s team and drafting by hand a 74-page crash course in Puerto Rican history. Without knowing much more about the record than the rest of us, he played the two available singles, “EL CLúB” and “PIToRRO DE COCO,” on loop as he wrote. Benito even passed along homework. “They asked for an entry on the animals in danger of extinction in Puerto Rico,” Meléndez-Badillo says. “So I had to do some research, read some scientific journals.” Concho, the stop-motion anthropomorphic Puerto Rican crested toad that co-stars with Morales in the short film and is featured on the album art, is an island native at risk of extinction.

When Meléndez-Badillo and I talk, the University of Puerto Rico has just been threatened with yet another round of budget cuts, imperiling mostly humanities programs, including history and Hispanic studies. It puts the album and the videos into perspective. Yeah, it’s a Bad Bunny record, but it’s also a textbook.

“I’ve gotten messages from teachers that are now implementing these visualizers in the classroom,” Meléndez-Badillo tells me, “and so many messages of people sending me pictures of themselves reading the slides, of their grandparents reading the slides, of their classrooms with the visualizers on. And comments from older Puerto Ricans, diasporic Puerto Ricans, thanking me for teaching them this history that they did not know.”

Benito has previously prickled at having to speak out about the state of Puerto Rican politics. “I feel like I’m an athlete representing Puerto Rico in the Olympics,” he told the New York Times in 2020. “It’s … diablo.” In 2023, he told Time, “That question could be a bit unfair because I simply do a song and then a responsibility so big falls on you — they’re not going to ask Daddy Yankee something like that.” But with this album especially, he seems to have settled into the role of un lector more comfortably.

“Benito, in this record, is very well aware of his agency as a Puerto Rican colonial subject,” Meléndez-Badillo says. “These things are not innate. We learn how to be political. We learn political ideologies.”

BALENCIAGA Round Jacket and Fitted Low-Waist Pants, at balenciaga.com. CARTIER Necklace and Earrings, at cartier.com. RAINBOW SANDALS Sandals, at rainbowsandals.com. BALENCIAGA Round Jacket and Fitted Low-Waist Pants, at balenciaga.com. CARTIER Necklace and Earrings, at cartier.com. RAINBOW SANDALS Sandals, at rain… more BALENCIAGA Round Jacket and Fitted Low-Waist Pants, at balenciaga.com. CARTIER Necklace and Earrings, at cartier.com. RAINBOW SANDALS Sandals, at rainbowsandals.com.

It’s impossible not to come off as sycophantic when making the case to take seriously what a Big Rich Celebrity has to say about politics. Their little Instagram posts or stump speeches or, God forbid, cringey sing-alongs are often too obvious or too rehearsed or too late and covered in icing. It’s almost always unself-aware. But how could you not believe Benito?

For one, money and fame can shield you from only so much when it comes to American imperialism. They can’t even get you — as in Benito’s case, when he cast his ballot in San Juan in November — the right to vote for president. It helps that he had been rapping and talking about what puertorriqueños call la brega (the struggle) long before some bigoted comedian went viral at a MAGA rally. And while, yes, he has the assurance that comes with wealth, Benito readily admits he still knows what it feels like when “acabas de ponerle las gomas nuevas que se te explotaron para que se te exploten otra vez” (you just installed new tires because the old ones blew, just to blow again) on the island’s perpetually underrepaired roads. Or how “tener una planta eléctrica se ha vuelto como tener una nevera, una estufa, sistema de agua potable” (having a generator at home has become like owning a fridge or a stove or a drinking-water system) because it’s not a matter of if but when the electrical grid will fail yet again. At one point during his time in L.A., the power in his house went out during a rare rainstorm, and he ran out in an instinctual panic to buy generators. His Puerto Rico now has more amenities, but it’s the same Puerto Rico that his family and friends, the same friends he’s had since he was a child, all live in. And it’s that Puerto Rico that he still craves.

The Monday morning we first met came after a long weekend for Benito that started with a parranda — a roving door-to-door house party, complete with live music, food, and drink, that’s a holiday-season tradition, like Christmas caroling but with seasoning — through Manatí on Friday night. Videos uploaded to TikTok show Benito, red Solo cup in hand, smiling and singing at strangers’ front doors, sometimes stepping inside as the crowd behind him grows. On Saturday, at rapper Residente’s concert, he was nearly swallowed by the floor pit in front of the stage at the Distrito del Centro de Convenciones in San Juan. Cameras captured him dancing, jumping, and smashing a beer can against his forehead. “Yo no tenía intención alguna de meterme para el público” (I had no intention at all of getting in the crowd), he says, but between the two Residente-branded beers he’d had — “Dos son suficientes para volverte loco” (two are enough to make you go wild) — and a medley of some tracks by Calle 13, the rap group Residente co-founded in the early aughts, he had no choice.

The weekend was like time-traveling for Benito. During the parranda, he bumped into a former co-worker from the Econo supermarket. “Él se me ve y me dice, ‘¿Mira, te acuerdas de mí?’ ” (He looks at me and says, “Hey, do you remember me?”), he recalls, smiling. “Nos reímos. Como que dije qué bueno estar aquí. Me di cuenta que estaba en el lugar correcto” (We laughed. It was like, It’s so good to be here right now. I’m in the right place). Even the concert, he says, was the past crashing into his present. He’d never actually seen Residente live because the last time he had tickets, ten years ago, he sold them to an acquaintance who became a best friend and ended up there with him that Saturday. “Entonces como que todo eso se mezcló y de momento en mi mente yo estaba en el 2014” (So it all kind of mixed together, and suddenly in my mind I was in 2014).

CRAIG GREEN Craig Green x Fred Perry Polo, Leather Lifting Belt, and Double-Pleat Canvas Trouser, at craig-green.com. CARTIER Necklace and Earrings, at cartier.com.

Eleven years and 1,606 miles later, I meet Benito again inside a different wood-paneled room: his suite at the Greenwich Hotel in Tribeca. It’s early January, the day after his Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon co-hosting gig and the afternoon following a stint on La Mega 97.9 FM. After our conversation, he’s scheduled to film an episode of Hot Ones. If the press run for the album is exhausting, I can’t tell through his pair of Héctor Lavoe–looking gold aviator sunglasses, though a five-o’clock shadow is starting to creep out around his goatee about four hours too early.

The room, like the rest of the city, is freezing. The shearling trapper that sits on his helmet of curls doesn’t do much to protect against the chill, so he mostly sits on his hands while perched on a velvet ottoman, rocking back and forth to get warm. The hat, he’d explained to me, is a sort of tribute to New York, the city that historically had the largest population of Puerto Ricans outside the island. “Yo de chiquito, alguien se iba para allá afuera, yo decía ‘para Nueva York’ ” (When I was a little kid, anyone who left Puerto Rico, I’d say they went to New York), he says. “Para mí todo Nueva York era Estados Unidos” (To me, New York was all of the United States). For the Puerto Ricans who came to New York, the cold was often their biggest worry, he explains, so he wears the hat for them — and to keep his head warm so his thoughts don’t freeze.

The cold was devastating to my father when he moved here with his family, hoping to escape poverty and become part of the more than 600,000 Puerto Ricans who migrated to the mainland between 1946 and 1964. When my 85-year-old father talks about it today, I can hear the little boy fresh off the plane. How much he missed feeling free, overwhelmed here by the traffic, the size of the buildings, the incomprehensible way everyone around him spoke, “like marbles in their mouth.” How his father, unable to handle the cold and harshness, soon returned to the island without looking back. How, decades later, as an adult, when we would visit Puerto Rico on vacations, my father would make sure to sit in the window seat of the airplane on the return flight. “I would look back and I would see the island,” he says, “and I felt so bad — like I’m leaving home.”

This is partly why Benito’s new album opens with a song called “NUEVAYoL.” At first, he admits, he couldn’t get past the idea that this record for Puerto Rico started in New York. But he figured there’s such a massive community of Puerto Ricans in the city, and for them to be here, at some point they had to leave there. “Entonces son puertorriqueños que una vez estuvieron aquí y tienen una conexión cabrona” (So these are Puerto Ricans who were once here and have an awesome connection).

As the album’s back cover reads, DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS is dedicated to all puertorriqueños on the island and everywhere else. “Porque creo que, al final del día, eso es lo que nos conecta: la cultura, nuestra historia, nuestras raíces” (Because I think that, at the end of the day, that’s what connects us: the culture, our history, our roots), he says. That inclusive call to the diaspora — to invite us back, to spur us to ask, maybe for the first time, “So what was it like to move here?” — is, in large part, what has made this record a global success. The album is a portal to Puerto Rico, not just for Benito but for the rest of us who can never know it the way he does. Through him, we can maybe get close.

Whether it would do all that wasn’t guaranteed. “La noche anterior a que salga el disco me levanté así a medianoche, como que ansioso” (The night before the album dropped, I woke up in the middle of the night anxious), he says. The loss of sleep, it turns out, wasn’t necessary. It debuted at No. 2 on “The Billboard 200,” earning the top spot by the following week and keeping it for weeks after that. It now holds Spotify’s record for the fastest album by a male artist to surpass 1 billion streams — beating out Un Verano Sin Ti. The title track topped both the Apple Music and Spotify global charts, and TikTok users made it the soundtrack to their own collages of family albums. On the day DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS dropped, Benito’s mother, Lysaurie, he tells me, had to take off her Apple Watch. So many friends and family members were messaging her, and she didn’t want them to spoil anything until she heard it herself.

In January, Benito announced a 30-show residency — No Me Quiero Ir de Aqui (I Don’t Want to Leave Here) — to begin later this year. This time, he has learned his lesson: All the shows will be at the Coliseo de Puerto Rico in San Juan. “Estoy bien excited de irme de gira pero en casa” (I’m really excited to go on tour but at home), he says with a smile, clasping his hands together. “Por la mañana, puedo estar allí jugando dominoes con mi abuelo, y por la noche puedo estar en la tarima” (In the morning, I can be there playing dominoes with my grandfather, and at night I can be onstage). To be able to have a routine, and a reason to stay, in Puerto Rico while still fulfilling his pop-star duties? The best of both worlds. Tickets sold out in under four hours.

Taking his hands out from under his baggy, light-wash jeans and spreading his arms in the air, he tries explaining to me how both the making of and the response to the album were like when Goku invokes his signature move, Genki Dama, on Dragon Ball Z. “Todo el universo, todas las personas brindándole su energía” (The entire universe, all the people give him their energy), he says. “Y él saca toda la fuerza de la gente. Es la gente dándole la fuerza” (And he takes all that strength from the people. It’s the people giving him his strength).

THE SOCIETY ARCHIVE Vintage White T 1950s and Vintage Leather Braided Belt, available upon request. ERL Unisex Distressed Chino Shorts Woven, at erl.store. CARTIER Necklace and Earrings, at cartier.com.

Production Credits

- Photographs by Emmanuel Sanchez-Monsalve

- Styling by Jessica Willis

- Photo Assistant: Zack Forsyth

- Digital Tech: Andres Vila

- Barber: Christopher Vargas

- Grooming: Ybelka Hurtado

- Manicure: Tairi Rosa

- Tailor: Rebekah Carrucini

- Production: A1 Productions

- Producers: Sigfredo Bellaflores and Guri Bellaflores

- Production Assistant: Jeremy Villanueva

- The Cut, Editor-in-Chief Lindsay Peoples

- The Cut, Photo Director Noelle Lacombe

- The Cut, Photo Editor Maridelis Morales Rosado

- The Cut, Fashion Market Editor Emma Oleck

Thank you for subscribing and supporting our journalism. If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the February 17, 2025, issue of New York Magazine.

Want more stories like this one? Subscribe now to support our journalism and get unlimited access to our coverage. If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the February 17, 2025, issue of New York Magazine.