This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Ron Howard began his Hollywood career in 1959, appearing in Anatole Litvak’s Cold War drama The Journey, his first credited role, when he was 4 years old. In the 1960s, he became a TV star as Opie Taylor, the young son of Sheriff Andy Taylor on The Andy Griffith Show. As the old studio system was dying, the New Hollywood era was emerging; Howard found himself in the middle of it with a starring role in George Lucas’s 1973 sleeper hit American Graffiti. By that point, Howard had already set his sights on directing and helmed his first feature, 1977’s Grand Theft Auto for producer Roger Corman, while acting as Richie Cunningham on TV’s Happy Days.

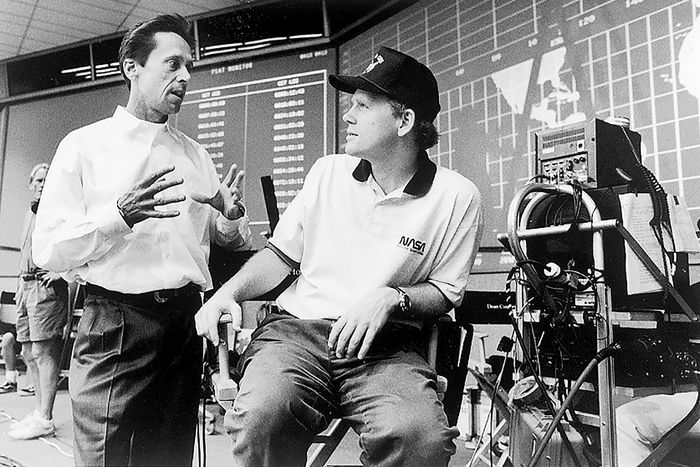

Since then, he has made many enduring movies, among them comedies Splash and Parenthood; blockbusters Cocoon, Backdraft, How the Grinch Stole Christmas, and The Da Vinci Code; and award-winning hits Apollo 13, A Beautiful Mind, Frost/Nixon, and Cinderella Man. His new film, Eden, an intense epic set in the 1930s about a group of people trapped on an inhospitable island in the Galápagos, tells a crazy story full of terror, bloodlust, and sexual abandon. You’ll find all the things Howard excels at as a director: an immersive sense of place, a fascination with extreme real-life personalities, and a nose for tales about families struggling under unimaginable pressure. As a director, a producer, and an actor, he probably understands the film business as well as anyone. “I do have commercial instincts and tastes,” he says, “but I’ve never really been driven by that.”

I’m sure everyone says this to you, but it is funny meeting you because I feel like I grew up with you.

Sometimes parents will want to introduce me to their kids and are kind of perplexed because they can’t really put it together.

Because the kids don’t necessarily —

“Oh, he was Opie when he was your age.” Well, that doesn’t mean anything to them. “He directed The Grinch.” “Oh, okay. The Grinch.” They keep fishing for some degree of connection.

My family came to the U.S. in 1980 from Turkey, and by that point, you had left Happy Days or were about to. But both that and The Andy Griffith Show were in heavy syndication. The early ’80s is also when the films you were directing were starting to come out. I was like 10 or 11, making the connection between somebody who was a little kid on a show, who was a teenager, and is now a director.

As a little kid, it didn’t take me long to realize that the director was the one who was hanging out with everybody. And a lot of our directors on The Andy Griffith Show had been actors, and I think Andy liked that. In fact, Howard Morris was the first one who said to me, “I think you’re going to wind up being a director because I see the way you’re curious about it all.” But I was 10, and I didn’t think much about it. It was really falling in love with movies that made me excited about being a director — The Graduate, Bonnie and Clyde, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, In the Heat of the Night, Romeo & Juliet — those movies just captivated me.

In fact, when my co-star Charlie Martin Smith and I were doing American Graffiti, one night we found out that The Graduate was on the second bill of the local drive-in. We went to get our Graduate fix and imitate Dustin Hoffman and look at all the shots. It felt accessible.

You’ve worked with so many different actors and gotten so many great performances out of them. And you obviously were an actor yourself for a long time.

Currently Emmy nominated!

Each actor has a different process. So how do you find the triggers to get the performances you need?

I can read them pretty quickly. Some actors want to be analytical; some don’t want to overthink it. Some love rehearsal; some don’t. The most extreme version of this I learned very early on Cocoon because I had seven veterans. Among the men, four different working styles. Wilford Brimley was totally improvisational. He was a younger guy and much more independent in his spirit and tone and sensibilities. He was more like Duvall or De Niro and wanted to be in the moment. And Don Ameche was an old-school Hollywood guy: “Tell me my lines, show me my mark, and I will deliver what the script suggests should be delivered and do what the director wants.” The other two guys were in between. Jack Gilford was a comedian. Hume Cronyn was a playwright as well as an actor. They could riff with Wilford a little bit. And it elevated the tone of this genre movie. There was an honesty to these guys that I really liked. But Don could not keep up with Wilford’s improvisational vibe. In rehearsal, he tightened up because he didn’t understand how to do that. And the writer and I started slipping him jokes and lines, things he could pretend were ad-libs. He started to feel so much better, and he wound up winning an Oscar as supporting actor.

When I had the script for A Beautiful Mind, I knew how strong it was, but I hadn’t yet done a full-on drama. We were getting ready to rehearse. And this is really name-dropping, but it was an act of giving and support I will never forget: I was in the production offices in New Jersey and got on the phone, and in one day I got through to Martin Scorsese, Mike Nichols, and Sidney Lumet and asked what they do in rehearsal periods. I said, “This is my first full-on drama, and I like to rehearse, but how do you use the time?” Mike Nichols said, “You want enough anecdotes so that maybe at three in the morning you can reference some anecdote that’s going to trigger something when they’re tired and really wish the night were over.” Lumet was more about freeing the actors by having enough preparation; he did a lot of mechanical blocking, but he said it was so that on the shoot day, it was all creativity. And Scorsese was more about finding each actor and understanding who could improvise, who needed the script, and somehow pulling all that together.

What’s the biggest disagreement you’ve had with an actor?

On Splash, there were a lot of choices I didn’t really buy, and I let them do it and then we did another take my way. But on the edit, I remember saying to Dan Hanley on the editing team, “If I ever get to work with Hanks again, I’m going to give him his head. He knows something.” And Russell Crowe is very much one of those actors where you may not recognize a nuance in the moment. Ana de Armas is also like that. You see it, you think it’s okay, it’s fine, maybe you try another couple of takes — you don’t see it advancing. But then on film, the nuance is there in a powerful way.

Oh God, I remember another one: Brimley in Cocoon. He hated coverage, and he didn’t like close-ups. He especially didn’t like having to repeat a scene. One scene, we did the wide shot, and he said, “Why do you need a close-up here?” I said, “Well, I need coverage to be able to control the rhythm of this scene.” He said, “They’re not going to let you control it anyway; you’re young. Those producers are going to take this movie away from you.” I said, “That hasn’t happened to me on any of my movies so far.” And he said, “Well, it’s going to happen on this one.” And I said, “Look, I need you to do this close-up, but I’ll bet you. If they force me to make even one cut, I’ll pay you $1,000. But if I can control the movie to the end, you owe me $1,000.” He said, “Okay.” And he still did the close-up in a pouty, shitty way, but I got what I needed, and we moved on. The studio, Zanuck/Brown, loved it. Then I screened it for Barry Diller, who is famously critical. I thought, Well, I’m going to lose the bet today. But he loved it. And I realized when I locked the movie, I’d gotten no notes. Everybody liked what I did! By the way, that would never happen today with all the executives determined to give you notes, but it was a much leaner operation in those days.

I wrote Wilford a letter that said, “Wilford, I want to thank you for all you contributed to this movie. Your improvisations elevated this movie in a way that I could not have dreamed of. But I do feel I should let you know that I won the bet, and I’d like you to make a donation.” I won’t say what it was, but I chose a charity that I knew he wouldn’t approve of. I said, “So please send it to X, Y, and Z address.” All I got back was an envelope with a $1,000 check and no note. He left it to me to make the donation.

The characters in Eden feel larger than life, and you get pretty extreme performances out of your actors. I could easily see another filmmaker asking them to rein it in. To what extent did you feel you had to push them?

Not much. Because we thought we were reining it in based on the real people. These were wild-ass characters most of them are playing. I cast actors who I knew had a kind of courage. One of the gutsiest things I’ve ever seen, especially once I met Ana de Armas, is that she did Blonde and pulled it off so beautifully. In conversation, she’s anxious; she was creatively anxious about the baroness. But when it came time to roll cameras, she was brave. And I felt that about everybody involved but especially the three women. Vanessa Kirby is very creative, and her character is the most mysterious in terms of what was written about her. But she was brilliant at piecing together a journey for Dore Strauch that I don’t necessarily think even Noah Pink and I understood. And Sydney Sweeney’s a little bit more that throwback kind of “Let’s just do it. Okay, I got it. Let’s not overthink it.”

De Armas in Eden. Photo: Jasin Boland

Eden premiered at Toronto last year. It’s got big stars, it’s got your name on it, but it’s just now being released by a small distributor. This comes on the heels of 2022’s Thirteen Lives, which was also well reviewed and star-studded. That came out on Prime Video and had a very small theatrical release.

That was a disappointment to me. Thirteen Lives would have been a theatrical feature. But COVID played hell. And in uncertain times, it is good just to get your movie out there. You make them for that theatrical experience, all of us do, even if that winds up being only the premiere and a handful of theaters. Eden was made as an indie. I had a script people liked. There was a SAG strike, and we got a waiver. We had to shoot fast. It was miserable. Everything’s an exterior set. If it rained, we had to stop, and we were getting these thunderstorms almost every day. My running gag was “The only cover we have is to shoot real fucking fast when the weather’s with us.” I’m glad it’s getting a theatrical release because I still think that gives every movie an imprint, almost like a hardcover publication of a book.

Do you feel your place in the industry has changed as a director?

Sure. It’s always been a changing thing in my mind. I’ve never felt like, Oh, this is it; I have to maintain this, because you’re only as good as your last film, even if you have a bank account and a good résumé. It’s much narrower now in terms of what’s proven to deliver an audience. But as a storyteller, streamers are fine too. So is longform television. I thought about trying to sell Eden as a six-hour miniseries or something, and I felt like, No, there’s enough of a thriller in there that I think you want to transport people and hold them.

Would you do a horror film?

I would do a psychological thriller. I loved The Exorcist. I wouldn’t do a slasher movie; that’s a little too real to me. But I would do supernatural if I could find the right story. I’m dying to find a contemporary sci-fi fantasy, like Cocoon or Her or The Shape of Water.

The Shape of Water, by the way, is a film not unlike Splash in some respects.

I haven’t found it, but I’m actively searching for something like Big Fish — that tone, that style. I love doing movies based on real events, but that pushes the aesthetic of the film into a more naturalistic vein. And if I could find a good fantasy where I connected with the themes and the character, it would open the door to something a little more visually poetic.

Your episode of The Studio, in which you play a fictional version of yourself as you’re given upsetting studio notes about a very personal film, was hilarious. Obviously, it’s a satire — but how accurate is it?

The neurosis and the strategic thinking, manipulation, lying, and hedging — all that stuff is 1,000 percent accurate. It doesn’t play out at that hyperspeed or with that intensity. But Anthony Mackie has a line in our episode where he talks about some neurotic back-and-forth, and he says, “Shit’s real.” I feel like shit’s real in the show. People don’t go at that pace, and they don’t wear their craziness on their sleeves quite that much, but there are plenty of war stories that would line up with what they’re writing.

What would you say is the worst note you’ve ever gotten?

There was a note that nearly prevented us from getting Splash made. There was this movie that Herb Ross was going to direct called Mermaid with Jessica Lange in the prime of her career as the mermaid and Warren Beatty as the human, the above-grounder. And the tremendous Ray Stark was the producer, and he was trying to kill our movie. In fact, this was a galvanizing moment in my relationship with Brian Grazer that ultimately would lead us to launch a company. We were taking the movie around everywhere, and they were all turning it down and they kept saying, “It doesn’t know what tone it is. It’s fantasy, it’s verbal comedy, it’s physical comedy.” And I kept thinking, What the hell is wrong with that? That’s a blend that works. It’s Frank Capra. Are you kidding me? I think they were all just looking for an excuse to pass because no one wanted to compete. Disney was on its ass at that point. They’d been making movies like Gus, about a field-goal-kicking mule. They were willing to take on the challenge, and Stark tried to bully Brian. He said, “I’m going to ruin you,” literally. And then he said, “Tell you what — I’ll let you be in my movie. You can co-produce it with me. Drop yours.” Brian, without a lot of money in his bank account, had the courage and fortitude to stay with it, even though Disney was a real B-studio at the time.

Something I noticed rewatching your films is that they have an interesting relationship with the female characters. There are a lot of characters in your films who could easily become just the spouse. But rewatching A Beautiful Mind, the second part of that movie is her movie.

I have three daughters and a very intelligent, thoughtful wife. I’m interested in women. I also like to get smart actors, and they all want to flesh things out. This movie wasn’t highly successful, but I’m so proud of Cate Blanchett’s performance in The Missing. Tommy Lee Jones was great too, but her character was the reason I wanted to make that movie.

Another reason I ask this is because I read the memoir you wrote with your brother, Clint, The Boys. You talk about how you guys gained a new appreciation for your mom much later in life.

I underestimated her. I put my dad on such a pedestal, and he deserved it, hell of a guy, but I realized that she was the reason the course of the family history changed. She was the one with the clarity and the vision. I totally missed that as a young man.

My dad said she was the best actor at the University of Oklahoma when they went to school there after World War II. She had come to New York and gone to the Academy of Dramatic Arts as a 17-year-old. Her parents, from small-town Duncan, Oklahoma, had enough money to let her go. But she got hit by a truck somewhere here in New York, and she then shied away. She went back to drama school in Oklahoma, where my parents met. The business was not kind to her. Later, after Clint and I left, she started acting again, dabbled, and went zero for 100 on auditions. She then went to an audition-scene study class and slowly but surely started getting work. She wound up in a few little things and started getting more confidence. She had a silent role, did some work on Cocoon, and really appreciated that, hanging around with Cocoon actors Jessica Tandy and Maureen Stapleton.

One day, Dad, who had never hocked me for work at all, called me when we had just gotten John Sayles’s rewrite on Apollo 13. He said, “I wanted to talk to you about that latest draft.” He said, “Your mother would knock that new Jim Lovell’s mother part out of the park.” And I said, “Oh, Dad. She’s just gotten back to doing it. I don’t know. I mean, that’s a pretty important role.” But he said, “Oh, she could do it.” “Well, she’s a little too young.” “Oh, you could age her easily.” “Okay. Well, I’d have to audition her.” But I didn’t want to bring her into the office. So I went to the house and I said, “Okay, let’s read through the scenes.” She was good. And I said, “But Mom, the thing is, you’re really too young to be this woman, to be Mrs. Lovell in an old folks’ home.” Mom was 62 or something. She said, “I could dye my hair, and they can increase my wrinkles.” And I said, “I don’t know.” And then she turned away and took her false teeth out and said, “Would this help?!” I said, “Okay, okay, okay! You got the part!”

I was very moved by the last thing she said to you guys.

At the end of her life, she couldn’t talk. I said, “Mom, do you want to write something?” “Yes.” She wrote it in this tiny squiggling, “Rance loves to act.” I’m getting a little bit emotional because it’s just … their relationship sums it up. She liked it enough to want to do it, but she knew that for him it was his lifeblood.

I was intrigued to learn that when The Andy Griffith Show first started, it was your dad’s idea to change the relationship between Opie and Andy into what it turned out to be.

Dad never said anything about that to me. Many years later, when we were doing a Return to Mayberry TV movie or reunion special or something, Andy told me that my dad had come to him very early on in the show and said, “You’re writing Opie the way most sitcom kids are written. They’re wiseasses and smarter than the dad.” And he said, “Ronnie can do that, but what if Opie actually respected his dad?” Now, I don’t know if Dad was just worried about me getting into bad habits, or I think he was, in his own very simple way, actually teaching me Actors Studio stuff. It was the simplest version of Method acting, finding the truth in moments. I think maybe he felt like there was a lot of artifice in these punch-line-driven deliveries that would be required.

In an excellent book from last year, Looking for Andy Griffith, by Evan Dalton Smith, he talks about Griffith’s legacy and how he became a surrogate father for so many people, starting in the ’60s and up to today. But if your dad doesn’t make that suggestion, this doesn’t happen.

Well, I think a lot doesn’t happen if he doesn’t make that suggestion. But look, I tried not to screw things up, and I was given a lot of advantages, including growing up on that show. The environment was super-creative. The show looks so simple, but it was all about this very precise problem-solving. I would see scenes suddenly become funny or work. Because it wasn’t done in front of an audience, and even though we were working quickly, what Andy wanted was a truthfulness. But it still required perfect timing and exactly the right tone. Andy was always annoyed that the media didn’t really embrace the show. In season five, I remember him saying, “How long do we have to be in the top ten for them to understand why this show works?” And then he started reading the Variety review out loud, and it wasn’t very flattering.

Click here to preview your posts with PRO themes ››

Howard with his mother, Jean, and father, Rance.

On Happy Days. Photo: ABC Photo Archives/Getty Images

Early on in Happy Days, they wanted to change the title to Fonzie’s Happy Days after Henry Winkler’s initially supporting character proved so popular. But you really stood up for yourself and wouldn’t let them.

I never, ever challenged what they were doing creatively. It made perfect sense that you’d build this Fonzie character and maximize that. But the optics of now being in a show called Fonzie’s Happy Days, my ego wouldn’t allow for that. I wasn’t bluffing. I would’ve left. And my contract, I’m sure, had no clause connected to titles. They could have said, “Fuck you. We changed the title, and we expect you to show up Monday morning.” But thank God for great bosses. Garry Marshall said, “If you’re not cool with it …” I later found out Henry himself thought it was a terrible idea. I think the position I took made it easy for both Garry and Henry to also say, “No, let’s not do that.” Years later, Henry said they were ready to do a spinoff and other things for Fonzie and he just said, “Why fix it if it’s not broken? My success depends on the ensemble I’m in.”

In your transition from Happy Days actor to director, you grew a prominent mustache in the 1980s. Tell me about shaving it off.

Oh, you heard about that? Brian Grazer got to know Andy Warhol, and Warhol said, “Ron Howard has grown this mustache.” He replied, “Yeah, well, he’s a director. He is trying to have more authority, look a little older.” Warhol said, “I’d like to photograph him and paint him, but I’d like to photograph him and paint him before with the mustache and then I’d want to shave the mustache and photograph and paint him again. But I’d want to shave it.” And I said, “You know, Warhol’s a really interesting guy, but I’m not letting Andy Warhol shave my mustache.” Pretty stupid. I think I could have a couple of original Warhols right about now.

But what really made it stupid was one night we opened a movie we had both produced: John Waters’s Cry-Baby. We loved everything about Cry-Baby, and we were so excited. We knew from test screenings it wasn’t for everybody. But we felt like, in a sort of niche way, that an audience is going to come charging out for this. In those days, opening nights would be a bit of an event. You could see the lines. We went to two or three theaters, and literally there were like three people, four people. It was shattering.

So we went back to Brian’s house. He had a tape of Drugstore Cowboy. We sat there having margaritas and watching Drugstore Cowboy and then we had maybe another margarita or two, and for some reason, we watched Drugstore Cowboy again. We loved the movie, but it’s the most depressing movie. We were depressed. And I literally went straight to the airport because it was now almost 3 a.m., 4 a.m., and I had to take a morning flight to San Francisco to meet with Industrial Light & Magic, George Lucas’s visual-effects studio, on something. I’d heard the Andy Warhol story, and truth be told, I was getting a little sick of my mustache. I just didn’t want somebody shaving it off and photographing it. That notion creeped me out. I had my overnight bag, and I went into the men’s room of the airport and shaved my mustache. I got back from ILM a day or two later. I’m in the office, and Brian says, “What happened to your mustache?” I said, “I shaved it.” “You shaved it?” I said, “I was so depressed after the movie, and I was a little drunk. I don’t know — I just said ‘Fuck it’ and I shaved it.” He said, “You idiot! You didn’t even want the mustache!” I think maybe Brian had a deal that he could have gotten a copy of the Warhol.

What would you say is the most personal film you’ve made?

Parenthood was just overtly personal. My kids were young. With Ganz and Mandel and Brian, I think there were 15 kids between all of us, and everybody contributed stories that were personal to them. I get so many screenwriters who come up and want to talk to me about Parenthood. Frost/Nixon screenwriter Peter Morgan once said to me, “It’s American Chekhov.” I mean, this is not somebody who throws compliments around. I passed that along to Ganz and Mandel right away. There were aspects of Hillbilly Elegy that were personal because I wanted to do something about the heartland that wasn’t a bank-robbing story or about farming.

What do you think the legacy of Hillbilly Elegy is now? Do you think about it?

I don’t think about it. I know it’s a mixed bag and probably quite culturally divided. I also know that reviews were bad and the audience-reaction rating was pretty good.

You obviously spent a lot of time with J. D. Vance back then; you did press together. Are you able to reconcile the person you knew and the character in the movie with the person you see now?

Am I able to reconcile? Well, it’s happened, so I know what I’ve observed. It remains a bit of a surprise to me. I would not have seen it coming, and I wouldn’t have expected his rhetoric to be as divisive as it sometimes is. By the way, I’m not following him or listening to every word.

I remember reading that the response to the film had really shocked him. [A spokesperson for Vance did not respond to requests for comment.] Did you get that sense at the time?

Yes, I did. He was frustrated by that. He loved Glenn Close’s performance and Amy Adams’s performance and liked the film. And he felt that, just as reviews had kind of turned on the book, his involvement was in some way tainting or coloring the critical response, and he resented it.

I remember some suggested the response to the film might have turned him even more to the right.

I can’t speak to that. When I was working with him, all his quotes about the administration were very public. He was trying to run an investment fund. So the run for Senate and the strategy he’s chosen to follow are not what I would’ve expected.

Have you had any interactions with him since then?

I did one text, after the election, which was just sort of “Godspeed. Try to serve us well.”

You are one of the only working filmmakers now who straddled a few different eras of Hollywood. Maybe Clint Eastwood is the other.

I worked with people from the studio system, but I never was a part of it. That wasn’t much around, though Harrison Ford told me he had a contract at Universal for a while before Graffiti that had expired. I asked Don Ameche a million questions about the studio system when I was doing Cocoon, just as I had asked Bette Davis, who I directed a few years before. Bette Davis implied it, but Don Ameche said, “Don’t romanticize that. That’s a trap.” He said, “It was socially a trap because we felt like we couldn’t go outside our bubble, because movies were the biggest thing in the world at that point.” They would tell you what to do every fucking time. And Bette Davis told me it took her 14 years to work off her seven-year contract because she was constantly being suspended for declining projects. Don didn’t; he played ball and regretted it. He became a massive star, but he said, “They relegated me to a lot of romantic comedies where I was this loopy second banana or something. Be glad you’re in a period where you decide what you want to do.”

What was Bette Davis like?

She was tough on me. She was in her 70s. She was not real happy with this 25-year-old guy from a sitcom directing this TV movie, but she really wanted the part. Then I cast someone who had never acted before in the role of a girl confined to a wheelchair. The actress was paraplegic, and I felt like she could bring a level of authenticity to it. Bette Davis was very upset about this. She said, “I have all my scenes with this girl. She’s 14 years old and has never acted.” She nominated several other candidates. I met them, auditioned them, didn’t feel they were a better way to go. I hadn’t met Bette Davis yet, but I called her and said, “I know you’re concerned about this, but I just want you to know I’ve made the decision to cast Suzy Gilstrap. I’m going to have a dialogue coach with her constantly, and I will protect you and make sure that your performance is excellent.” And she said, “Well, Mr. Howard, I really disagree with this decision.” I said, “I understand, but the network supports my choice, and I think it’s going to be right for the spirit of this film.” She said, “Well, Mr. Howard, I suppose we’ll have to see.” And I said, “Ms. Davis, please just call me Ron.” And she said, “No, I will call you Mr. Howard until I decide whether I like you or not,” and hung up.

So now I’m really thrown. I’m not far from shooting, I’m not sleeping well, and I mention it to my dad. He said, “Look, she’s an Oscar-winning actress. She’s a tremendous talent. She therefore knows she needs to be directed. Every great actor knows they need help. And so do your job. Don’t overcompensate. You’ll be fine.” I did a little research and saw that William Wyler was her favorite director. He wore a suit and tie on the set every day, so even though we were shooting in Plano, Texas, in August, I showed up in a corduroy sport coat and a tie. Man, that was fucking hot. Anson Williams was producing, and he fought to send a limo to pick her up at the airport. She said, “That’s the first time anyone’s sent a limo for me in 15 years.” She appreciated that. She had her whiskey and her unfiltered Camels. That was her whole perk package.

It’s the first day we’re shooting, and she’s playing an aerobatic pilot. We have a mock-up, and I’m going to twist the camera the opposite way, and she’ll lean a little, and it’ll look like she’s inverted. She’s not really getting it, so I give her a bit of guidance. I walk up to her, and she reacts: “Oh my God!” Loud enough for the whole crew to hear. “Oh, you frightened me! I saw this child walking toward me, and I couldn’t help but wonder, What of any consequence could this child possibly have to say to me? ” And she does the Bette Davis laugh with the Camel: “Hahahahahahaha.” So I laughed and leaned in and said, “When the camera goes this way, if you lean the other way, it helps with the illusion.” She said, “Okay, fine, fine.”

So I go back, and I’m popping Tums and wondering what this will be like. Through the whole day, she’s very tense, doesn’t talk to me much. We get to one scene, we’re blocking; she has to make an exit, but it’s a little awkward. I said, “Oh, Ms. Davis, try that again, and I would try leaving the line earlier, then maybe do the second line on the walk and then maybe just try the last line at the door.” She said, “Oh, that won’t work.” And I said, “Well, just try it for me. Let me see.” She said, “Sure, of course I’ll try it. That’s me, I’m always the director’s kid! Hahahahaha!” So we did the little rehearsal, and even before she got through the door, she said, “I see what you mean. That works. Okay, let’s shoot it.” So we did it. We went through the rest of the day. Now, it’s about 4:30, and I said, “Ms. Davis, that’s a wrap for you. Great first day. Thank you so much.” And she said, “Okay, Ron, see you tomorrow,” and slapped me on my ass. From that point, she was okay. She was great with Suzy, by the way — not icy with her for a heartbeat.

You resisted sequels and franchises for a while but did eventually do the Robert Langdon films. I liked The Da Vinci Code, but by Inferno, which didn’t do as well and whose release was delayed by almost a year, were you tired of making these?

I loved doing those, especially The Da Vinci Code. All three of those movies tested really well with audiences in our preview process. I was reluctant with Inferno. Hanks wanted to do it. He said at one point, “Come on, we don’t want to break in another director on this, do we?” And he cajoled me. It was lucrative, and it was going to be another great adventure. I mean, my God, we wound up living in Florence, shooting in Venice, Istanbul. So I went into it pretty clear-eyed. And I also felt, Well, we all agreed it was going to be a trilogy, and we’d close it out with that one.

I liked Solo a lot, too, but that also underperformed and was affected by the behind-the-scenes drama.

I’d always been curious about Star Wars, and Solo landed in my lap when I didn’t have another movie set to go. My wife, Cheryl, and I were vacationing in Paris. I went to London to see Hans Zimmer play at the O2, and I reached out to Kathy Kennedy just to say “hi.” And she said, “Do you want to come to breakfast?” I said, “Okay.” Also the late Alli Shearmur, who I had worked with before, and Jon Kasdan eventually showed up. They basically said, “We’ve reached a creative impasse with Lord and Miller. Would you ever consider coming in?”

I looked at some edited footage, and I saw what was bothering them. There was a studio that liked the script the way it was and wanted a Star Wars movie, but there was a disconnect early on tonally, and they weren’t convinced that what Phil and Chris were doing was working effectively. I couldn’t judge that because I didn’t see enough of it to know. But they were sure. Once I said, “Okay, I think I can do this script, and I think I understand what you want of this script,” they said, “We’d want to reshoot a lot.” I looked at the whole movie and then pointed out some things that I thought were great. And Phil and Chris were incredibly gracious throughout that process. They were just seeing two different movies. So I came in, I had a blast, but there’s nothing personal about that film whatsoever. It’s still just a shame. I can’t wait for Phil and Chris’s next movie.

What did George Lucas tell you?

I talked to him once early, when I was just thinking about doing it. He wasn’t active on the films, but he said, “Just don’t forget — it’s for 12-year-old boys.”

Earlier, you directed Willow for him. What kind of latitude did you have on that?

George really made it a collaboration. I always felt, at the end of the day, This is George’s movie. It’s his idea. He’s putting his money into it, even though he didn’t talk about it. He was the first to give me final cut, but I knew I would never exercise it.

There’s a monster in Willow called the Eborsisk — after critics Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel — and one of the main bad guys is called General Kael, after Pauline Kael. How has your relationship to criticism changed over the years?

The Eborsisk and Kael! They were more Lucas’s idea. But I was upset at that time with Siskel and Ebert. They’d given Night Shift and Splash two thumbs-down. George was upset with Pauline Kael. So we got giddy with the idea of poking a little fun at the critics. Later, I got to know Siskel and Ebert both and liked them. In the year Apollo 13 was nominated, I actually won the Directors Guild but was not nominated as a director at the Oscars, and Siskel on the red carpet went off mic and leaned into me and said, “I think you make it look a little too easy.” I took that as flattery of the best kind.

Is there a film from your career that you wish more people would’ve appreciated?

I love The Paper. But it never got a foothold outside of six or seven cities that still had major newspapers. That was already a dying idea — small towns had lost their papers and so forth. It played like a $100 million movie in New York and Boston and Toronto and San Francisco and L.A. and Chicago. Everywhere else, it was a disaster.

Do you consider any of your films a disappointment?

The Dilemma. It’s the last comedy I made, and I liked doing comedies. But it was a shocker, and from the test audiences, you could just see it didn’t have it. Vince Vaughn, Kevin James, Brian Grazer, Universal, people who do a lot of comedies, we all thought we had something here. And it turned out that infidelity was not funny to people. We were pretty smugly certain that it was. And it had some sequences I was really proud of. Channing Tatum gives me credit for teaching him and the world that he could be funny because he was great in this one sequence. Everybody worked real hard on it and believed in it. But it was an interesting example of being tone-deaf at that time.

Do you want to go back to comedy? You were good at it.

I’m not sure that my tone is in alignment with what is commercial in terms of comedy. That’s what I loved about being around Arrested Development. Those are ways for me to exercise the comedy muscles in a way that works. Live-action comedy is demanding something that isn’t necessarily in my wheelhouse. And it doesn’t travel very well, and global audiences mean more than ever. Physical comedy can travel. But not the kind of character comedies I like to do.

Do you ever find yourself thinking in “the Ron Howard voice” from Arrested Development?

No, I don’t! But I love it when I bump into it online or as a meme. And that was so fun because I had always had the idea of a narrator, but Mitchell Hurwitz hadn’t written it in the initial script. The visual style and the cutting pace and so forth had been born out of a project we had with Steven Spielberg and Jeffrey Katzenberg called Pop.com in ’99 and 2000. We were trying to do shortform entertainment on the web. It was too early, the bandwidth wasn’t there, and we spent on the wrong things. But we thought a lot about shortform entertainment. I was trying to think about the new grammar of reality television, and I thought that could be applied to a sitcom. I pitched that to Mitchell, and he said, “I love that.”

Do you feel you’ve been properly appreciated in your career as a director?

Yes. If you put on a lie detector, there might be a little squiggle because I sometimes feel that my origin story has caused some people to fold their arms and say, “Color me skeptical.” But I don’t actually believe that’s true because I think expectations are pretty high for me. My tone and voice might not be for everybody, but for a lot of people, it works.

Thank you for subscribing and supporting our journalism. If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the August 11, 2025, issue of New York Magazine.

Want more stories like this one? Subscribe now to support our journalism and get unlimited access to our coverage. If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the August 11, 2025, issue of New York Magazine.

One Great Story: A Nightly Newsletter for the Best of New York

The one story you shouldn’t miss today, selected by New York’s editors.