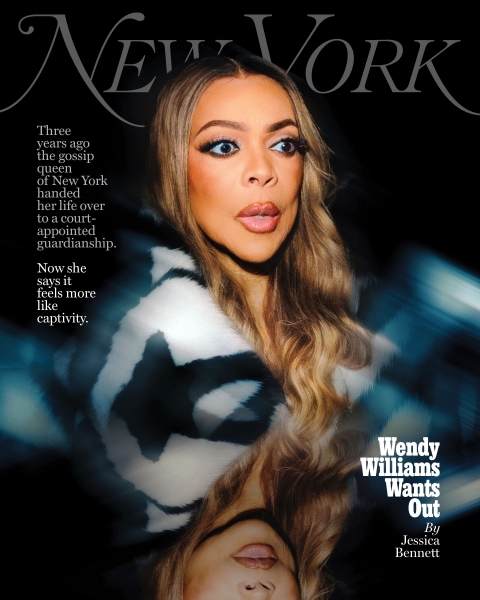

At LaQuan Smith’s New York Fashion Week show in September.

This article was featured in New York’s One Great Story newsletter. Sign up here.

On the last night of New York Fashion Week, in September, Wendy Williams, the former talk-show host and onetime gossip queen of New York, given permission to leave the locked floor of her assisted-living facility, where she is held against her will, was seated in the front row of designer LaQuan Smith’s runway show, showing the world just how well she was doing. She was polished up in long lashes, makeup perfectly set, dirty-blonde hair in smooth, loose waves. Smith had dressed her in a cropped black-and-white fur jacket over black shorts and fishnet stockings.

Williams, 61, had begun reappearing in public early this year after a long stretch of silence: In 2022, she was placed under court-appointed guardianship; then, last year, her guardian announced that the star had dementia, an assessment Williams vehemently denies. On her way into the show, she’d waved to fans who cheered and shouted that they loved her. Inside, she was surrounded by celebrities of her heyday: She’d been hip-hop-radio royalty in the ’90s and early aughts and made her name talking shit about everyone in the scene. A few seats to her left was Busta Rhymes, who once tussled with her friend Charlamagne Tha God over an interview she had conducted. She chatted with Lil’ Kim and asked for her number — Kim, who’d called her a “hating bitch” after Williams critiqued the rapper’s nose job. The children of Diddy — Williams’s longtime nemesis, who she’d frequently implied was closeted and who had once gotten her taken off air — were milling nearby.

In This Issue

Wendy Williams Wants Out

See All

A few days later, on Friday night, she arrived in a black SUV at Tucci, the upscale Italian spot on the busy corner of Broadway and Bleecker. In a white mini-shirtdress, the top buttons undone and cinched at the waist with a wide Gucci belt, Williams stepped down to the curb, with her bodyguard’s assistance, in heavy-soled black boots. She was escorted inside to a corner table by a window, where she could be seen unobstructed from the street, visible to photographers who’d been alerted in advance, by her friends, to expect her presence. Joining her at the table was Laura Geller, the makeup artist, and Max Tucci, Williams’s friend and the restaurant’s owner, who leaned toward her, phone in hand. He swiped through photos taken at the LaQuan Smith show, showing her pictures of herself.

Anyone who watched her, wondering what was true, looking for signs that she was off or disoriented, would have noticed that her eyes were open unusually wide, as if alarmed or confused, and seemed to bulge — but this was a symptom of her Graves’ disease, an autoimmune condition that strains the ocular muscles. They would have seen her teeter a bit on her feet on her way inside, holding on to her bodyguard with one hand — a Birkin-like croc bag in the other — but this could be explained by her lymphedema, which causes swelling in the feet and ankles and trouble balancing.

An hour or so into the evening, Tucci, in a crisp button-up, stopped by the table where I was eating with a friend one floor down. “She looks amazing,” Tucci said when I asked how Williams was. “She’s doing great.” I asked about the Coterie, her high-end assisted-living facility in Hudson Yards. “She calls it a dump,” he replied, shrugging and chuckling. “She says the people there are like” — he slumped his head to the side and stuck out his tongue. “This is, like, where billionaires send their grandmothers. But, you know.” His tone became serious. “She doesn’t need it. Wendy doesn’t lie.”

Williams’s guardianship had begun when her bank, Wells Fargo, filed a petition stating that she was not competent to manage her financial affairs and was at risk of exploitation. The arrangement was at first temporary, and Williams has said she agreed to it. In court proceedings, she was referred to as the AIP, the “alleged incapacitated person,” and records of the case were sealed to protect her privacy. But the news leaked almost immediately, and a wild ecosystem of rumors grew around her: Fans theorized that the COVID vaccine had triggered a neurological decline; that the guardianship was a plot by the bank to steal her money; that photos of her looking ill or disoriented — in blue hospital socks and no shoes on a wet Manhattan street, for example — were pictures of body doubles; that Diddy, her forever adversary, was somehow responsible.

Then, in 2024, more than a million people saw footage of Williams appearing addled and often bedbound in a Lifetime documentary. But what exactly ailed her was unclear: She was shown frequently drinking, andGraves’ disease, a diagnosis she’d revealed publicly in 2018, can trigger cognitive problems. The cast of characters orbiting her in the doc, in her $4.5 million Fidi duplex, was also confusing: a new manager who was in fact her jeweler; a new publicist who oddly had come to her through her estranged ex-husband’s attorney (an attorney who would later falsely claim to represent Williams); very few members of her family; and only one visiting friend, the model Blac Chyna. They spoke about what was happening to Williams in vague terms, referring to “some kind of memory issues going on” and the idea that “she needed rest.” In response to the documentary, herguardian publicly revealed that doctors at Weill Cornell Medical Center had diagnosed Williams with frontotemporal dementia — a neurodegenerative disease that affects behavior and language more than memory — and progressive aphasia, a related condition affecting speech.

This January, Williams began a type of campaign on her own behalf, twice calling in to “The Breakfast Club,” hosted by Charlamagne Tha God. “I’m not cognitively impaired,” she said. She sounded purposeful and angry, describing the guardianship as “disgusting” and the Coterie as a “luxury prison.” She was especially offended by being kept in the memory unit. “These people,” she said. “There’s something wrong with these people here on this floor.” Williams’s fans united in a Free Wendy movement — far smaller than the crusade on behalf of Britney Spears (a petition on change.org garnered 26,000 signatures) — and that spring held sparsely attended protests on Hollywood Boulevard in L.A. and on 35th Street outside the Coterie.

In her conversations with Charlamagne, Williams jumped from topic to topic, at times trailed off, and made a few outrageous comments — referring to her former manager, whom she no longer trusted, as “the Black man” and asking Charlamagne how her breast implants looked by the light of a window in a recent TMZ appearance. But she’d always been that way to some degree: impulsive, chaotic, risqué. To her fans, it was what made her fabulous. “I love when you call,” Charlamagne told her, “because I think people are reminded of how erratic you are. This has nothing to do with anything other than Wendy Williams being Wendy Williams.”

A month later, Williams appeared at a full-length, fifth-floor window of the Coterie, waving to paparazzi below — in turns frantic and placidly posed for the cameras. By then, what was both known and definitively true was that Williams could have no visitors in the facility, that she needed the permission of both her guardian and Coterie staff to leave, that she was not allowed to have a cell phone. On the landline in her room, she could make only outgoing calls — she could not receive any contact from anyone. In a long brunette wig, a white T-shirt, and gold bangles, Williams raised her left arm and pressed her palm against the glass, as if to demonstrate her enclosure. At some point, she dropped a handwritten note from the window to the street below. It read HELP! WENDY!!

That September night at Tucci, she sat with her friends for three hours. At the end of the evening, her bodyguard ushered her outside and hoisted her, by her underarms, a bit like a child, into the back of another black SUV.

In her studio at WBLS in 2005.

“This whole thing is about money, money, money, money.”

It was August, and on the phone was Joe Tacopina, the celebrity lawyer known for representing A$AP Rocky in an assault trial and defending Donald Trump against sexual-assault accusations. “I speak to this woman almost every day,” he said. “Wendy is in control of her faculties.”

Tacopina had begun identifying himself as Williams’s “personal lawyer” in the spring, making the rounds on TMZ, Extra, and Sirius radio, calling the guardianship “unjust” and “despicable” and demanding a jury trial. “Get me in front of a jury for five minutes,” he told me, “and I’ll get the quickest verdict of my life.” Technically, or at least according to the court, Tacopina doesn’t represent Williams in any capacity. But he’s one of many keeping near the star, circling the affair, waiting for an opportunity to arise.

Vanishingly few people close to Williams believe her life should be restricted as it currently is; many believe the guardianship in its current form is inhumane. Multiple close friends, as well as her publicist and niece, have denied she has dementia at all. Many close to her have accused the guardian, an elder-care attorney named Sabrina Morrissey, of serious failings; some allege neglect and cruelty. Members of Williams’s family say Morrissey has kept them from having any contact with her for months at a time; has denied them basic information about her well-being and her whereabouts; and at times has failed to even make sure Williams is safe.

Some, including Williams herself, have alleged that Morrissey — who is paid between $250 and $450 an hour — is corrupt, knowingly profiting from the forced dependence of a capable adult. Other Williams contacts have said the star is the victim of a larger conspiratorial scheme. One of the people closest to her told me that “high-level, high powerful individuals” are responsible for keeping Williams contained: “It’s way bigger than it looks.”

And yet it doesn’t take much to peel back the layers of self-interest among those pushing for Williams’s freedom. Some stand to profit from her potential ability to return to work: Her publicist, Shawn Zanotti, and former manager Will Selby both pursued projects for Williams while she was obviously not well. The scandal itself also appears to be lucrative: Both Zanotti and Selby asked how much this magazine was willing to pay for an interview with Williams. (New York does not pay subjects for interviews.) Tabloid publications have consistently paid for access to her.

Williams’s ex-husband Kevin Hunter, who says his former spouse is competent, has alleged that the judge in the case is crooked — accepting political contributions from Wells Fargo and Williams’s court-appointed attorneys to fund her reelection campaign. In June, he filed a lawsuit in federal court describing the guardianship as “fraudulent bondage,” accusing 48 parties of wrong-doing, and demanding Morrissey’s immediate firing. For years, Hunter had received $37,500 a month from his ex-wife in alimony, according to sealed court documents — money he has not collected since shortly before guardianship proceedings began. His lawsuit asks for $250 million in damages to be shared between his ex-wife and himself.

Williams’s three guardianship attorneys, the only lawyers recognized by the court — who are supposed to represent Williams’s interests as they see them — are not authorized to speak to the media. One suggested, however, that my investigation into the case should become an article about the lawyers themselves and followed up with a highly edited photo portrait of herself.

“It’s like this big pack of losers,” one longtime friend of Williams’s said: so many scrummaging over the case, fighting for a reward.

The costs for Williams, meanwhile, are astronomical: An apartment on the memory floor of the Coterie, where she does not want to live, costs $25,800 monthly. Her estate is responsible for paying for the guardianship lawyers, Morrissey’s fees, and an attorney for Morrissey on a $10,000-a-month retainer. Although the exact state of her finances is unknown, lawyers have said in court this year that she needs money, and in 2024, Morrissey sold the star’s 2,400-square-foot apartment, reportedly at a loss. (Somewhere along the way, Morrissey rehomed Williams’s two beloved rescue cats, Chit Chat and My Way. On “The Breakfast Club,” Williams said she was shocked to learn they were gone.)

In the coming weeks and months, a new medical report is expected to be presented to the court, which could reaffirm the court’s previous decisions and the guardianship as it stands. But Williams wants out, and the judge, Lisa Sokolov, could decide to reconsider Williams’s case overall. She could rule that the restrictions on Williams are too severe and should be eased or that Morrissey should be replaced. The court could also choose to end the guardianship altogether.

Sources close to the case said the last outcome is unlikely — Williams would need to prove that she no longer requires any supervision at all. But the truth is that her actual needs and abilities may no longer matter. “Most people subject to guardianship do not have it terminated,” said Nina Kohn, a legal scholar who specializes in the system. You may enter the arrangement voluntarily, she told me, but you cannot leave it of your own free will. Williams cannot get out the same way she came in. In August 2024, according to previously unreported documents, Williams formally revoked her consent for the arrangement and made an adamant plea for its termination. Instead, the guardianship was recategorized as “indefinite.”

When Williams asked to be released, Sokolov reported that Williams had been “very direct,” exhibited an “exuberantpersonality,” and was “full of ideas.” But it was clear, the judge wrote, that her aphasia had worsened over the prior two years, and Williams allegedly expressed a desire to give her family more money than she had to her name. She was not capable, Sokolov said, of “planning for her future, handling her money, and protecting herself from exploitation.”

At the same time, the judge noted that Williams “is not the typical AIP … She can accomplish many of her activities of daily living on her own.” But inexplicably, and in direct contradiction of New York State law, which requires that those in guardianship have as much autonomy as possible, the guardian remained in complete control of Williams’s life.

Sean “Diddy” Combs on The Wendy Williams Show in 2017.

By her own telling, Williams has always been over the top, and her great trick was in embracing it. Born in Asbury Park, New Jersey, but raised in the largely white suburb of Wayside, she grew up in a family, she’s said, that was like the Cosbys, and she was like Denise, Lisa Bonet’s character, the troubled middle child. “I was the thing that did not fit in my family,” she told New York in 2005. As she grew, her parents developed codes to attempt to manage her in public. TL meant she was being “too loud.” TF was “too fast.” TM was simply “too much.”

Her parents prized education: Her father was a high-school principal who later taught English literature at a local college, her mother was a special-education teacher, and her younger brother would eventually teach as well. Her “perfect” older sister, Williams has said, excelled in school and became a lawyer. Wendy graduated high school 360th out of 363 students. But she had her sights set on a different kind of life.

Williams began DJ-ing while in college at Northeastern University in the mid-’80s and then — after a brief stint in the Virgin Islands — rose through the ranks of New York radio before landing the afternoon-drive slot at Hot 97, the storied hip-hop station that gave rise to a generation of DJs including Funkmaster Flex. She quickly made a name for herself, spinning the hits but also serving up celebrity gossip and sex and dating advice. In 1993, she was named Best on Air Radio Personality by Billboard. The next year, she met her future husband, Hunter, at a skating rink in New Jersey.

On air, Williams was brutally honest about herself, describing hating her body and her choice to get liposuction and a breast augmentation (from an A/B to larger than a double D); her yearslong addiction to cocaine; and learning of her husband’s infidelity shortly after their son, Kevin Jr., was born in 2000. In interviews, nothing was off-limits. Williams advised Mary J. Blige to pull a “Tina Turner” and “find a nice white man” overseas. When she spoke to O. J. Simpson after his criminal and civil trials for the killings of his wife and Ron Goldman, she didn’t mention the murders but asked him, “When was the last time you slept with a black woman, O.J.?”

By 1998, Williams had been immortalized in a Jay-Z lyric and an entire Tupac Shakur diss track. She would later feature in a Mariah Carey song and a diss track by Will Smith. Both Smith and Tupac were subject to Williams’s most controversial radio pastime: outing rappers she believed were gay or down-low. (She thought Smith was gay; Tupac, she suggested, had been raped in prison.) That same year, Diddy, according to her 2003 memoir, Wendy’s Got the Heat, successfully pressured her bosses at Hot 97 to push her out, leading to a three-year exile at a radio station in Philadelphia. As she would put it later in an interview with Philadelphia Weekly, far more subtly than she’d said it on air, “Puffy has the secret … Listeners know if they listen to the show.”

It was in Philadelphia that Wendy introduced her signature catchphrase “How you doin’?” — a greeting, in an exaggerated lilt, that was also code for reading someone as gay. Her fans loved it, shouting it at her on the street.

In 2001, Williams returned to New York radio with her own syndicated show on WBLS, a Hot 97 rival, and there, in 2003, landed what she would later call the “crowning jewel” of her career: a playful, testy interview with Whitney Houston when the singer was at the height of her drug use. Off the bat, Williams suspected Houston was high and suggested they had something in common — cocaine — then asked about her husband, Bobby Brown’s, recent stint in jail for drunk driving. Williams eventually made her way around to telling America’s former pop princess that she could imagine her and Brown having “wild, circus sex.” “You nasty-ass bitch,” Houston responded with a laugh. “You’re nasty, boo.” A few years later, Williams was inducted into the Radio Hall of Fame.

The first episode of her daytime TV talk show, The Wendy Williams Show, aired live on Fox in 2008 and quickly gained mainstream traction with a mix of high drama and vulnerability. She wore loud prints, flashy rhinestone and diamond jewelry, and extra-long false lashes and rotated through a collection of around 50 wigs, which she talked about often and sometimes adjusted on air.

The members of her audience were her “co-hosts,” she used to say, and she made the studio feel like a boisterous family gathering. From her purple velvet armchair, she opened each show with a 21-minute riff, a campy sermon — funny and judgy — on the day’s celebrity news (Lindsay Lohan’s arrests; Nicki Minaj’s marriage). It was all seemingly made for the social-media era — Williams provided endless clip fodder — and in 2014, Wendy beat out more established talk series like Ellen and Dr. Phil, reaching more than 2 million homes.

As her celebrity grew, Williams’s personal life remained small and restricted. Hunter, then her manager, her producing partner, and an executive producer, despite having no TV experience, was seen by many, according to several former employees of The Wendy Williams Show, as a menacing presence, including in the studio. Arrivingin a green Ferrari and often wearing a fur coat, he traipsed through the set with a bottle of tequila, smoked weed in his office, and frequently berated staff and Williams. It was rumored he controlled his wife’s personal life and prevented her from spending time with the people who might otherwise have been her close friends.

According to previously unreported testimony from her sister, Wanda Finnie, it was in the late 2010s that Williams’s cognitive abilities began to decline and in 2017 specifically that she began to have memory problems. Former staffers on Wendy noticed changes too. Though they said the host’s memory remained sharp throughout her years on the program, by the mid-2010s, she seemed to get easily confused, sometimes trailing off mid-sentence during meetings and having trouble reading her cue cards. The latterissue was so marked that producers developed new ways of communicating with the host, including color-coding cues, limiting them to a few words per line, and flashing a red light to signal that Williams should use the word allegedly.

These tools seemed to work. If staff gave her cues like KIM K — PLASTIC SURGERY / BRITNEY — DIVORCE, Williams would know exactly how to fill in the story. And when she messed up — as she often did — it was usually charming. “Messiness was part of her brand,” said one former producer. “It was part of the reason why so many people related to her.” It also made it very difficult to know if Williams was unwell or just being herself. “She was so eccentric, and so fun, and so quote-unquote messy,” another former staffer said, “that it was a hard line to differentiate.”

In the fall of 2017, Williams fainted on air while wearing a glittering Statue of Liberty Halloween costume. She claimed she’d simply overheated, but the incident fueled speculation among staffers about her health. Her behavior had become erratic — she would be sharp in the morning and “loopy” by the afternoon, as one producer put it. According to a later investigation by The Hollywood Reporter, staff began finding alcohol bottles hidden in ceiling tiles around the studio. In early 2018, Williams revealed her Graves’ disease on air and announced on the show that she would be taking a three-week hiatus.

She took another leave the following year, which she again said was due to Graves’, as well as to vertigo, though she spent the time at a rehab facility for substance abuse in Florida. When she returned to the show, she informed viewers that she was living in a sober house. The next month, the news broke that Hunter had impregnated another woman, and Williams filed for divorce.

When COVID came the next year, Wendy producers attempted to film the program in Williams’s apartment. But in the few episodes that made it to air, she seemed drunk or otherwise zonked out, and Wendy @ Home was called off by May. The same month, the show’s music director, Clyde Joseph Jr., known to viewers as DJ Boof, found Williams unresponsive in her apartment, and she was rushed to the hospital. Williams’s nephew would later say that she had required three blood transfusions.

Click here to preview your posts with PRO themes ››

Williams last appeared on her show on July 16, 2021. Neither she nor her viewers knew it would be her final episode. When the program was set to resume in the fall, Williams couldn’t be found, and Fox ultimately began the 13th season without her. The show went on for almost another year, buoyed by a series of guest hosts. When the show was canceled in February, according to The Hollywood Reporter, Williams was not personally informed — supposedly because no one, including her manager, could reach her. She learned the news from her niece, who read it in the paper. In repeated conversations with the show’s executives that spring and in various public appearances, Williams seemed to either not understand what was happening or be in denial. In March, she told Good Morning America that she would soon be back on air, “bigger and brighter.”

The public had not yet caught wind of it, but by then, Williams was under guardianship. It hadn’t been only the show’s staff that weren’t able to find her in the fall of 2021; to friends and acquaintances in New York, she’d seemed to disappear for long stretches. By early January, her longtime financial adviser, Lori Schiller, who usually spoke to Williams every few days, had grown alarmed, as had Bernie Young, Williams’s manager at the time. Young suspected Williams was in Miami, where her 21-year-old son, Kevin Hunter, Jr., went to college. Much of her family lived in and near the city, and she’d often retreated there: after her divorce, during a handful of attempts to get sober, and while dealing with the symptoms of Graves’, which can cause extreme fatigue.

Then, on or around January 18, at Schiller’s request, the Miami Dade Police Department went to Hunter Jr.’s apartment to check on Williams, according to sealed court filings. At that time, however, both Williams and her son were at a nearby branch of Wells Fargo, where Hunter Jr. was asking to be granted his mother’s power of attorney. They were accompanied by an entertainment lawyer named LaShawn Thomas, an attorney for Williams’s ex-husband, Hunter Jr.’s father. Williams was allegedly “unresponsive,” “disoriented,” and “barely able to write,” and the bank said “no.” Two weeks later, Hunter Jr. returned again with his mother. This time, Thomas was on speakerphone, and the two demanded that the bank allow him to withdraw $25,000 of his mother’s money. They also insisted he become the primary contact for her financial affairs. A withdrawal of this size, the bank decided, was “out of character,” and the transaction was blocked. In response, Hunter Jr. and Thomas allegedly berated employees. Williams, appearing weak, stood aside in silence. When staff tried to speak with her, Hunter Jr. intervened.

It was days later that Wells Fargo filed its guardianship petition, in New York State court, asking for a third party to take control of Williams’s finances. Among its claims, the bank wrote that it believed Williams was being “unduly influenced by her son Kevin, and perhaps others.” The application included a letter from an Upper East Side psychiatrist who’d been treating Williams for more than a year for an unstated condition. He wrote that in the preceding six months, Williams had been “unable to make reasoned decisions.” “Her judgment and insight,” he said, “are severely impaired.”

Arriving for dinner at Tucci in September.

“Where are you on your journey right now, Wendy? What do you want?” a voice off-camera asks. Williams is seated in her purple velvet chair, now in the living room of her Manhattan apartment. In a tight black dress, an ash-blonde wig, and pink lipstick, she is upright, blowing smoke from a vape, looking displeased. A strand of pearls hangs low on her chest.

“Well, I’m glad that I’m free from The Wendy Williams Show,” she says haltingly. “So now I can absolutely pull this down” — she begins to stretch the bodice of her dress toward her nipples, then pauses and asks if she can show them. “Well, no,” the off-camera voice says awkwardly. Williams snickers, then flips off her interlocutor, smiling.

These are the opening moments of Where Is Wendy Williams?, the Lifetime documentary that premiered in February 2024, nearly two years into the guardianship. Seconds later, onscreen, Williams introduces Selby, her then-manager and friend, who commissioned her trademark diamond-encrusted W necklace. (As a jeweler, he’d also worked for Drake.) “My …” she pauses, “sexy best friend.” She begins to sob. In an instant, she’s smiling again, telling the camera with a wink that she’s “gorgeous, sexy, and fabulous.”

The more-than-three-hour doc was shot from August 2022 to April 2023 — the last nine months that Williams lived in her own home. Her world is shown to be both extremely circumscribed and chaotic, and she vacillates between lucidity and incoherence, cheer and agitation. In a rare walk outside, as paparazzi swarm, she shouts, “Please, I’m famous! Fuck you!” To a nail technician, who arrives for an at-home appointment, she asks, seemingly unprovoked, “Are you stupid?”

Selby, a fixture at her side, plays the role of caretaker, checking that Williams has eaten, hiding vodka bottles from her, coaxing her out of bed, and helping her pick out her clothes.

At one point, Zanotti, the publicist, takes her to Los Angeles for a meeting she’s set up with executives at NBC who, she tells Williams, may want to bring back her show. The meeting is not filmed, but in one moment, Williams seems to believe she’s in Miami. When Zanotti mentions that the Oscars are the coming weekend, she replies, “What’s Oscars?” During lunch at a rooftop restaurant, Williams orders multiple Grey Goose cocktails. Zanotti tells the camera that Williams is fine: “She knows her limits.” In a car after the meeting, Williams tells the doc’s producers that she took off her boots for the executives and showed them her feet. The conversation, Zanotti says, was “amazing.”

Throughout the doc, members of Williams’s close family and a childhood friend express deep worry and frustration with the guardianship. Alex Finnie, her niece, tells the producers she lives in fear of seeing a headline that something has happened to her aunt. Hunter Jr. says he believes Morrissey “has not done a good job of protecting my mom.” In the doc’s final installment, he claims that his mother was previously diagnosed with alcohol-related dementia.

Hunter Jr. was an executive producer on the documentary, as was Selby, who arranged for Williams to appear in it and earned his own fee and a cut of Williams’s pay. Williams, too, is listed as an EP, though it’s uncertain if she ever understood the film was being made. She was paid $82,000 in total, far less than the $400,000 she was allegedly promised.

Following the doc’s premiere, Williams’s family, friends, and associates began to talk, breaking a gag order over the case. Her niece, Alex Finnie, told Nightline that her family had been “shut out” of Williams’s life and that she hadn’t seen her aunt in nine months. Williams’s brother, Tommy, told Us Weekly that his sister was “stuck” in the system: “We just want to be able to check in with her … but where do I go? No one knows anything.”

Zanotti, meanwhile, claimed she’d been misled about the film — that it was supposed to be about an imminent comeback for Williams. The filmmakers themselves, facing a barrage of negative reviews and criticism for filming a woman who may or may not have been in a position to consent, claimed they were never informed of Williams’s diagnosis. “If we had known that Wendy had dementia going into it, no one would’ve rolled a camera,” Mark Ford, an executive producer for Lifetime, told The Hollywood Reporter. “At a certain point,” he added, “we were more worried about what would happen if we stopped filming.” He said the crew had often found Williams alone in her apartment, where they were concerned she might fall down the stairs, and that she was frequently without food. He also claimed they’d tried to reach Morrissey at various points during production but, Ford said, “we either got a terse hang-up or a very brief, unpleasant exchange.” (When contacted, Ford declined to clarify.)

Morrissey, a 60-year-old widow who lives in Manhattan, immediately mounted a defense of her role as guardian, filing a lawsuit, technically on Williams’s behalf, that accused Ford and his production company, along with Lifetime and its parent group, A&E Networks, of exploiting and humiliating Williams for profit and asking for an unspecified amount of damages to go to Williams’s estate. Through her lawyers, Morrissey alleged that Williams, “a severely impaired, incapacitated person,” could not possibly have agreed to being filmed and claimed she did not consent on Williams’s behalf. Contradictorily, however, she admitted she’d known the documentary was taking place. She asserted she too was “actively misled” about its direction by both the producers and Selby. (In a counterfiling,the filmmakers denied this.)

Diane Dimond, an investigative journalist who appeared in the doc and who has written a book on guardianship, told me that Morrissey certainly seemed to be in “arrears on her obligations.” “Where was she?” Dimond asked. “Why wasn’t there someone there making sure Wendy wasn’t getting liquor deliveries?”

Morrissey is barred from discussing Williams’s case but in a court-approved statement said, “Wendy has never been neglected, deprived of food, or harmed by the Guardian.” She said the family has never been denied information about Williams’s whereabouts and well-being and additionally alleged that she has not received any payments for her services “since the first few months of the case” and that the other involved lawyers had also not been paid.

The situation was worse for Williams than it appeared on film. She threw valuable art and jewelry down the trash chute of her apartment. She allegedly punched a home health aide and locked another out of the house. She routinely threw away unspoiled food and subsisted on V8 as well as the ever-present vodka.

Williams received the diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia shortly after the final days of filming in May 2023. According to sources close to the family, Williams’s family and staff were never directly informed of the diagnosis. (Morrissey denies this.) A few months later, Williams moved into her studio apartment in the Coterie.

In August, I visited the building in Hudson Yards; by then, she’d been there about a year and a half. In the lobby were fresh lilies and a marble fireplace. A tiered crystal waterfall chandelier hung overhead. The place’s amenities are impressive: an urgent-care facility and imaging lab; a rehab center for physical therapy; a 24/7 nursing staff. The lights in the hallways were “circadian,” according to a brochure, dimming in a way that can apparently minimize the confusion that plagues residents who “sundown.” The dining room, a tour guide explained, used pottery in warm colors — copper and burnt orange — which they said has been shown to stimulate hunger. For those residents able to partake, there was a private movie theater with red velvet reclining chairs and a snack bar, a hair salon, and a spa.

In a model unit on the third floor, a “transition floor,” the guide said, where some residents stay while they wait for a room to open in memory care, floor-to-ceiling windows overlooked 35th Street. The bathroom, all marble, with heated floor tiles, was equipped with safety bars. Williams had initially been on the third floor. Then in July, on her birthday, she’d gone up to the building’s penthouse restaurant and bar, where panoramic views of the Hudson River and nightly music played on grand piano might allow one to forget one’s surroundings. Williams had gotten “hammered,” as one friend put it. Soon after, she was moved to the memory unit.

That floor, unlike the others, smelled of Febreze. As we walked, the guide explained that there were no locks on the apartment doors and no stoves or refrigerators for residents’ safety. I tried to imagine the Williams the public knew living here. A man in a wheelchair was nodding off in the hallway; in a recreation area, a group of residents stared at what appeared to be a rerun from Shark Week.

We were rounding the corner to the floor’s gym, where an elderly group was practicing t’ai chi, their canes resting against a wall, when I spotted Williams: She was on a treadmill, facing a row of tall windows overlooking the city. She wore a black top, leggings, and her usual sandy-blonde wig. She looked good.

It was more than a year after the documentary before anyone in Williams’s circle submitted any formal complaint on her behalf. A health-care advocate eventually filed one with Adult Protective Services in New York, statingthat they had serious concerns about Williams’s rights and well-being. (To date, APS has not replied. When contacted, a spokesperson said the agency could not comment.)

Hunter’s lawsuit may not seem exactly valiant — it’s unclear why an ex-husband would be entitled to damages or even to sue on his former spouse’s behalf — and Williams’s lawyers have called the suit “detrimental” to her interests, but the case is the only known legal action taken against the guardianship by her family and defenders. This fact gnawed at me. If everyone wanted Williams freed, or at least freer, why wasn’t there more of a fight?

According to people close to the case, the family has considered various legal paths but has never committed to an approach. “There are family dynamics at play here,” said a close source. “They cannot agree on what should happen. And the reality is as long as they aren’t united, they’re not going to convince the court of anything.”

Williams’s sister, Wanda Finnie, is said to have expressed interest in becoming the guardian early on. Some say she didn’t follow through, while Finnie claimed in the documentary that she believed she’d accepted the role, “and then all of a sudden,” she said, “the wall came down,” and she was cut off from her sister and the court.

Hunter Jr. petitioned to be his mother’s guardian long ago, in March 2022, but was denied by the judge. The court knew Williams had allegedly raised concerns about her son in the fall of 2021, months ahead of the incidents at Wells Fargo. According to sealed documents, she’d told Schiller, the financial adviser, that “under no circumstances was she to permit her family, including her son Kevin, access to her accounts or assets.” Williams said she believed Hunter Jr. — at the time living in a condo she was paying for and receiving a monthly allowance — may have been “stealing” from her. Williams asked Schiller to “lock her accounts if something were to happen to her and Kevin attempted to access her account information.” The two women referred to these potential circumstances as “doomsday scenarios.” It was soon after this conversation that Schiller stopped being able to reach Williams. When she eventually got her on the phone, Williams said she was in her son’s Florida apartment and that he’d taken her cell phone and wouldn’t let her speak to anyone. She said she wanted to go home to New York.

Throughout the years that Williams was abusing alcohol, it was not uncommon, a source close to the family told me, for her then-husband, Hunter, to ship her down to Florida, take away her phone, and isolate her until she dried out. It was possible, this source said, that Hunter Jr. was simply emulating the approach he’d seen his father take many times. “But,” the source said, “he did it sloppy.”

When I reached Hunter Jr. by phone in September, there was a hint of panic in his voice: “What’s happening? Did something happen?” I assured him that his mother was fine, as far as I knew. Like the rest of the family, he’d had only limited contact with Williams since Morrissey was appointed more than three years before. He had not spoken publicly since the documentary.

“I kind of have my career right now,” he said. “I do work in education, and I’m really not trying to be too caught up in this.” He meant, in part, the media circus. He was soft-spoken and sounded genuine and a bit sad. In a second call, later that month, he told me, “I’m trying to build, carve out my own path right now, away from everything.” When I asked if he would like to respond to the multiple accusations that he’d attempted to steal from his mother, he replied, “None of that stuff is true. I am all for getting my mom out of the situation she’s in, because I love her a lot, and that’s the only thing I’ve ever cared about. It’s not about me — it’s about her. And I just want her to get out of this. Because it’s not right.”

By late summer, as Williams’s next hearing approached, many of her friends and family had gone quiet. Williams’s niece Alex and her sister, Wanda, did not respond to repeated requests to speak. Neither did her nephew Travis Finnie. Her ex-husband Hunter declined to talk through his lawyer, Thomas, who also declined to comment.

Suzanne Bass, a former co–executive producer on The Wendy Williams Show, was one of very few people willing to speak on the record. “Honestly,” she said over the phone, “she’s the best I’ve seen her in years.” Like so many, Bass hadn’t had contact with Williams during the first three years of the guardianship, and until recently, the documentary was all she had to go on. “She’s vibrant now,” Bass said. “She sounds clear, and she sounds excited for her future. She wants her old life back.” Though Bass would not comment on Williams’s diagnosis, she said she deserved at least some modicum of freedom. “My mother has Alzheimer’s,” Bass said. “She lives at home with help. Even if that’s Wendy’s condition, there’s no reason for her to be locked up.”

When I reached Selby, the former manager, in late September, he said he hadn’t spoken to Williams in a while. He would say little but told me that he loves her and cares about her well-being.

Zanotti, the publicist, who said she doesn’t believe Williams has dementia — “This woman doesn’t miss a beat” — told me she still hears from the star almost daily. Williams had been pleased that I was trying to get in touch. “You know,” Zanotti said, “she doesn’t want to be forgotten.”

“It’s Wendy.”

The call came in on a Saturday night while I was out at a bar. NO CALLER ID.

I headed to the bathroom — single stall — and put Williams on speakerphone.

She knew I’d made it into the Coterie. “Well, first of all,” she asked, as I fumbled to lock the door, “what did you think about the living situation?”

I started to say that I was actually impressed by it, though of course I could understand what she’d been saying, but she cut me off: “It’s a dump! Did you see the people? The elderly people? Why do I want to look at that? This is a fucked-up situation. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve asked that I be moved from this floor.”

She brought up her landline and the fact that she couldn’t receive calls, only make them. It made her furious. She’d recently gotten access to an iPad, which meant she could finally read the news. “Sabrina,” she said — Morrissey — “did not want me to have it. You have me stuck on this expensive floor with these dying people, and I can’t have an iPad?” She went on: “The judge doesn’t like me, and I don’t like the judge, but she permitted it.” Williams had been using the iPad to listen to herself on her old radio shows.

I asked when she’d last seen her family, but she didn’t want to answer. I asked about her daily life: How much was she getting out? What about leaving for dinner or to socialize?

“Uh, excuse me,” she said, supremely irritated. “You know I’ve been out. So obviously I do go out.” She mentioned Delmonico’s — Tucci’s other restaurant — and Peter Luger. I started to tell her I live next to Luger, but she was already going: “That neighborhood is a zero!”

“Everything that I do is here in this room,” she said. “So I … I try not to eat here.”

Several of Williams’s friends had told me that she was more isolated and lonely than she let on. Her social world had always been small. In interviews before the guardianship, she would often say, “I don’t have friends. I have a show.” But “if before it was a circle,” one of her friends told me, “now it’s a dot.” Williams was also bored. Tucci had said she’d been sewing her own clothes with a needle and thread. She had very few of her own things at the Coterie — most of her designer goods and everything else she owned, by no choice of her own, were in storage — but it was also a way of passing time after the elderly people on her floor, as Tucci put it, “pass out at dinner.”

On Sundays, Williams said, she’d been going to church — a new thing for her — in Brooklyn. “It’s a megachurch, by the way,” she told me. “And I like that, you know? It gives me faith and keeps me very well in touch with God and myself.” The pastor, she said, had been on The Wendy Williams Show back in the day. On a recent Sunday, the massive concrete building was packed. The sanctuary looked like a studio stage, complete with a camera crane gliding over the crowd.

Our call didn’t last long — Williams had little patience for all the questions. But she sounded the way she’d always sounded on air: confident, a little cutting, meandering, brazen. “I’m an icon,” she said at one point, reminding me who I was talking to. When I mentioned I’d seen her in the gym, she brought up her lip and breast implants. Both had been done when she was 31, she said. “And you know what? It’s still hitting and holding.” But as far as the conversation wandered, she knew why she was calling.

“So,” she said. “How do you think I sound?”

Thank you for subscribing and supporting our journalism. If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the October 6, 2025, issue of New York Magazine.

Want more stories like this one? Subscribe now to support our journalism and get unlimited access to our coverage. If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the October 6, 2025, issue of New York Magazine.