In December, the film director Mira Nair was in India preparing for her upcoming feature, Amri, about the life of the Indo-Hungarian painter Amrita Sher-Gil, whom she called “our Frida Kahlo.” She said these whirlwind weeks, which involved her jetting from Amritsar, next to the Pakistan border, to Kochi, near the subcontinent’s southern tip, were “deeply painstaking but thrilling because this particular film has taken me four years to cook and now we are lifted off.” The trip to India, she said, was also her “first time being in the rest of the world” since her 34-year-old son, Zohran Mamdani, won election as mayor of New York in November. “I’m in alleys and villages, and suddenly I hear people running behind me, shouting, ‘Mira Nair?!’ They’re young.” And what they were yelling was “‘We love your movies! But your son!’”

We were sitting in Nair’s Morningside Heights home above a Manhattan blanketed in slushy snow less than a week before New Year’s Day, when Mamdani would be sworn in as the city’s first Muslim mayor. Nair shares the apartment, which is owned by Columbia University, with her husband, Mahmood Mamdani, who has taught there since 1999. The space was packed with books and photographs and art and, on this morning, filled with siblings and in-laws who had arrived in recent days from India and East Africa. They had eaten bagels and lox from Zabar’s and sorted through a collection of hats, seeking garments that would protect them from what would turn out to be a bitterly cold Inauguration Day.

Nair may be the most globally famous living Indian filmmaker. Salaam Bombay! (1988) was the first Indian film ever to win the Caméra d’Or at Cannes and only the second to be nominated for a Foreign Language Film Oscar. Mississippi Masala (1991), starring a young Denzel Washington and Sarita Choudhury as the romantic leads, is a lush meditation on love and displacement, critically acclaimed for its nuanced depiction of the friction between marginalized groups. Her biggest commercial hit, Monsoon Wedding (2001), was among the highest-grossing foreign films ever released in the U.S. at the time and led to Nair becoming the first Indian woman to win Venice’s Golden Lion.

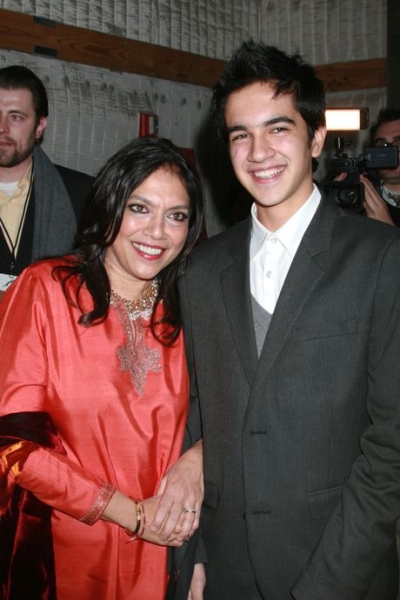

From top: 1992: With Zohran at the Mississippi Masala premiere in Hollywood. Photo: Barry King/Alamy Stock Photo2007: At the Gotham Awards. Photo: Hen… more From top: 1992: With Zohran at the Mississippi Masala premiere in Hollywood. Photo: Barry King/Alamy Stock Photo2007: At the Gotham Awards. Photo: Henry McGee/MediaPunch/IPx

That Zohran Mamdani was highborn is no secret. It was among the curious features of his moon-shot mayoral campaign, in which critics often portrayed him as a nepo-baby product of the city’s most rarefied climes. According to common depictions of his family’s dynamic, Mamdani inherited his leftist political ideology from his father, the anti-colonialist Columbia professor, and his dimpled charm and flair for the theatrical from his filmmaker mother. But the connection between Nair’s career as an artist and her son’s as a politician is far more significant than the fact that they share some Hollywood stardust.

A hallmark of Nair’s work is her insistence on telling stories of exile, familial dysfunction, and prejudice with humor, sex, bright colors, and buoyant music. She believes it is her job to keep “bums on the seats,” to find the joy amid the tumult: “ ‘Anything but homework’ is what I say!” It’s a philosophy reflected in her son’s bread-and-roses mayoral campaign in which the cool fonts and scavenger hunts and exuberantly multi-lingual ads made a platform focused on affordability and inequality feel like anything but a lecture.

It’s just one of the ways Mamdani’s political persona is a close echo of his mother’s filmmaking sensibilities. “Sometimes art is spoken of with a lightness, as if it has a lack of rigor or depth,” Mamdani told me in January at City Hall. “Growing up with my mother, I learned just how difficult this work is. She would say, ‘You have to have the heart of a poet and the skin of an elephant.’”

She was describing life as a filmmaker, but it’s not bad advice for a politician. People who know them both agree that qualities mother and son share—sky-high ambitions for themselves, boundless confidence—are key to understanding the unlikely paths they have forged in the world.

“When I think about where Zohran comes from, I think about how Mira made history,” Nair’s longtime agent, Bart Walker, told me. “There was no woman auteur from India having films distributed in the U.S. to a general audience. There was no Mira before Mira, no precedent for her; she blazed her path with talent, charm, and will in superabundance. Sound familiar?”

Walker’s description so clearly applying to New York City’s mayor is not incidental: This is the woman who joked to the journalist Mehdi Hasan at her son’s Election Night party, “I am the producer of the candidate,” and who said at his inauguration, “I am going to be the mother of New York City.” These proclamations are loving, ebullient, and funny (Nair’s own mother used to tell reporters she was “the producer of the director”), but they also explain a lot about how Mamdani became Mamdani, who, in Nair’s telling, often seems as much her creation as her works of art.

Inadvertently or not, Nair raised her son to be the type of man who believes he could be mayor of America’s largest city despite having few credentials for the job, instilling him with determination, showing by example how to defy and exceed expectations, and swaddling him in layers of adoration. “I believe you have one chance to raise a child,” Nair told me, “and if you can marinate them in love like we have, with the notion that they will be secure and protected in that embrace of love, which is not a small one but a larger one, that gives a lot of strength for the life ahead.”

Another family might have produced a raging narcissist. So far, Mamdani is simply among the most exciting politicians of his generation. Nair added, “I don’t think our son has changed because he is so strongly buffered by this embrace. Really.”

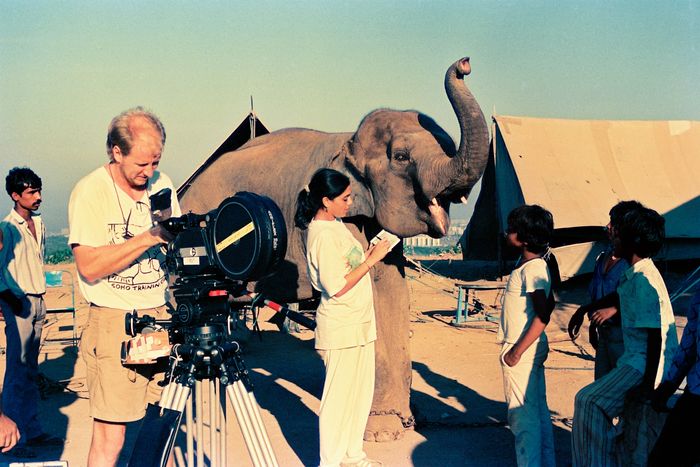

1987: On the set of her breakthrough film, Salaam Bombay! Photo: Sooni Taraporevala

Nair was born in 1957 in Rourkela, India, in the eastern state of Odisha, to an upper-middle-class family. Her father, Amrit, a high-ranking civil servant, was born in Punjab before the partition that divided the subcontinent. Nair was closer to her mother, Praveen, a social worker. (Her parents would eventually separate in 1990.) After a year at Delhi University, Nair left India in 1976 to attend Harvard on a scholarship.

At the time, there were only a handful of South Asian undergrads at Harvard. Among them was Sooni Taraporevala, who would become one of Nair’s best friends and a frequent screenwriting collaborator. Taraporevala recalled Nair, at 19, as “absolutely flamboyant,” wearing a winter coat that doubled as a cape, and driven like an engine toward what she wanted. When legendary Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray came to Boston, Nair and Taraporevala lined up with friends around the block to see him. “Suddenly, she disappeared and we never saw her again,” said Taraporevala. “We never got in, but she had and was sitting at the master’s feet.” Taraporevala said that her grandmother, who loved mischievous people, adored Mira and used to call her “Tohfaani avee,” Parsi Gujarati for “the Storm Has Arrived.”

Nair had fallen in love with her Harvard photography teacher’s assistant, Mitch Epstein, and the couple spent the summer of 1978 in New York, then moved to the city full time after Nair’s 1979 graduation. “She was dynamic, on the go, with a Rolodex of people to meet,” said Taraporevala.

“I came here, really in many ways, to be an actor,” Nair told me in an earlier conversation we had before Thanksgiving. She had won Harvard’s Boylston Prize for Elocution, performing Jocasta’s speech from Seneca’s Oedipus, and in New York she became enraptured by the downtown theater scene. She apprenticed at La MaMa with Ellen Stewart and immersed herself in the work of other artists who electrified her: Joseph Chaikin, Andrei Serban, and Elizabeth Swados, whose 1978 musical Runaways, about homeless New York City youth, planted a seed for Nair that ten years later became Salaam Bombay!

For a time, Nair waited tables at the since-closed Indian Oven on Columbus. That job, she said, helped her understand “the levels of immigrants in our country. At that time, the illegals were in the basement, Mexicans skinning the chickens. The quasi legals were on the first floor above them, Bangladeshis cooking the food. Then it would be the legals above, who would run the show and, frankly, abuse us all.”

She and Epstein briefly lived on West 93rd Street and then West 19th, where they paid less than $300 in rent; their night-out meals cost $7 at Empire Szechuan on 96th and Broadway. “All the SROs were on Riverside; you were told never to walk on Riverside,” Nair remembered. “It was a very down-and-out time in New York but also very vibrant.” Epstein’s mentor was Garry Winogrand, with whom they would socialize; Joel Meyerowitz lived nearby.

After graduation, Nair worked at an African-art gallery on Madison Avenue during the day; it was always empty. “That was the time I used, surrounded by great Nubian art that no one came to see, to write grant proposals for my documentary-filmmaking career,” she said. In the evenings, she would head to West 57th Street, where she’d gotten a job syncing sound for medical films.

“Next door to me, also editing at night, was Robert Duvall, who was cutting his first feature film, Angelo My Love, which was about Gypsies, and he insisted I was a Gypsy. It began a very interesting friendship, where I would edit films about backache and he would edit Gypsies. New York is like that, full of unusual juxtapositions.”

Nair eventually got one of those documentary grants. Her first film, 1983’s So Far From India, was about a newsstand worker in New York who travels back to India to see his wife and young son. Like so much of her work that would follow, it was about a search for home.

Nair said that, from the start, she wanted to tell the “stories of those who are unseen.” She said she’d never plotted out a career, but “I was clever in the sense that I was pitching stories that if I didn’t do them, no one else would. That was my shtick.”

Two years later, she made India Cabaret, about striptease dancers in Bombay, and, in 1987, Children of a Desired Sex, about the use of amniocentesis in India to determine fetal sex. But by the mid-’80s, Nair said, “I wanted a greater audience for my work,” and she was itching to move beyond documentaries. She began to develop, with Taraporevala and Epstein, then her husband, a feature film about children living on the streets of Bombay.

“People told me it was an impossible film to even begin to think about,” Nair said, both because of the subject matter and how she wanted to approach it, as “an amalgam of fiction and nonfiction,” casting child actors from the streets and “treating them as if they were the best stars in the world.”

“I imagined that it would be a small indie film,” Taraporevala recalled of Salaam Bombay! “We didn’t have all the money, but she didn’t say that. She was fundraising while we were shooting.” The speed with which the film got written and produced was startling. “I call it Mira Magic,” said Taraporevala. Days after Nair finished editing, Salaam Bombay! was screened at the closing gala at Cannes, where it received a standing ovation, the audience prize, and the Caméra d’Or. In the New York Times, Vincent Canby praised it as possessing “a free-flowing exuberance.” Nair was 31.

She remembered coming home from Cannes that year and going out for dinner with Epstein. By then, they were living in a loft on the Lower East Side. When they walked into their new regular restaurant in Chinatown, she saw Jim Jarmusch, who had won the Caméra d’Or for Stranger Than Paradise a few years earlier. “I didn’t know him then, but I remember just giving him a handshake and a hug,” she said. “Two Caméra d’Ors in Chinatown, New York. It was a spirit of camaraderie.”

In 1990, Nair began work on Mississippi Masala, teaming again with Epstein and Taraporevala and for the first time with Lydia Dean Pilcher, who would become her longtime producing partner. In researching the movie, about Asians forced from Uganda by Idi Amin, she tracked down the work of Mahmood Mamdani, a scholar who had written about the expulsion.

Mamdani was organizing a conference on academic freedom at the same time Nair was filming in Uganda’s capital, Kampala. Pilcher recalled how “we would film all day and then have dinners with these brilliant minds at night. Students were protesting. We were telling this story of deeply personal experience happening in a global context.” In this heady atmosphere, Nair and Mamdani fell in love. She ended her marriage to Epstein, married Mamdani, and was soon pregnant.

She and Mamdani were in New York, living in a “very small, elegant apartment on Barrow Street” that she loved, she said. “But when you give birth in our part of the world, you have your family with you to help. And there was nowhere to put them. So we decided very impulsively to go to Uganda when I was seven months’ pregnant.”

So Nair left New York City for the same reason so many people leave it today: real estate and child care. They purchased the Kampala house overlooking Lake Victoria, in which they had shot parts of Mississippi Masala. “It was beautiful but a shack,” she said. “It didn’t even have a kitchen. We went there simply because we could have our families with us when I gave birth, which was a reckless decision.”

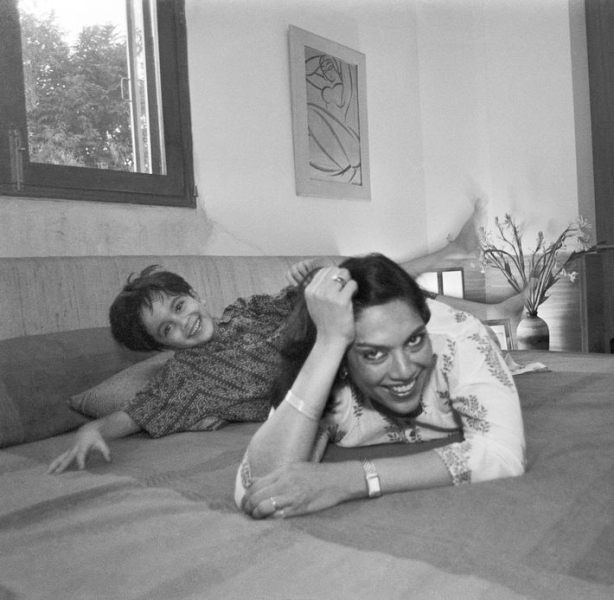

Zohran was born just a couple of months later in Kampala and came home to a house full of grandparents and friends. “It was a great choice to have him be born there because it’s idyllic,” said Taraporevala. “It was Mahmood and Mira, Baby Zohran, her in-laws, and her mother. It was a lovely time for her, I think.”

Now, Nair told me 34 years later, “people really curse me out. Because he can’t be president.”

1991: In Kampala with Zohran and Mahmood at the house overlooking Lake Victoria. Photo: Courtesy of the subject

“During my pregnancy and even through Zohran’s birth and breastfeeding, I was making a film on the life of the Buddha,” Nair said. The movie would not ultimately get made, but her work on it colors her memories of early motherhood. “I created a little nook in my husband’s study where I could feed him at night, with a lamp and a book stand and him in my lap; I used to call it the milk bar.” She’d nurse while reading the Buddha’s teachings and Sir Edwin Arnold’s narrative poem about the life of Prince Siddhartha Gautama, thinking about “equanimity and what is enlightenment, what is humanity, how kindness and connectivity and empathy were such a foundation of what he taught.”

The baby, she said, “was never a crier. I remember only when he had an ear infection once.” What she recalls more distinctly is his laughing. She and Mahmood used to strap him into a Sassy Seat that could be hooked up to the dining table. “It was Zohran and Mahmood and me, and we would just laugh. He would laugh and his little legs would shake”—here she gives a happy shimmy at the memory—“and he would get excited about all the laughter, and we would just sit around laughing. That was our life, as crazy as it may seem. It was just a sense of cheap joy, you know?”

Last summer, when Zohran celebrated his marriage to the artist Rama Duwaji at the Kampala house he lived in as a child, Nair’s toast to the couple touched on her memories of that first year. “I did say to him, ‘The Buddha is in you,’” she told me.

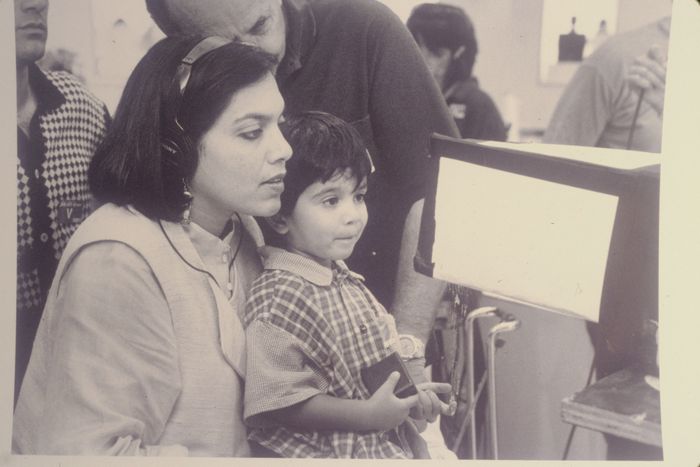

For those first few years, mother and son were inseparable. “Even when Zohru was a little fellow, he was always with me when I was shooting or promoting,” Nair said. She is proud and grateful, she said, to have “never had to drop a day of work” as a young mother thanks to her mother and her in-laws, who “used to band together, a triangle of three. They had a very good friendship, and I was so happy.” For the first six years of Zohran’s life, the “caravan” of care would go to every set. “I would work 15-hour days and come home and there would be food and everything, just like a home,” said Nair.

Coming from a family built around the twinned priorities of care and work made an impression on Zohran. “I’ve thought a lot of them not just as parents individually or as aspirations professionally,” Mamdani told me, “but in terms of what a marriage can look like, pursuing your professional dreams and being able to raise a family all at once. And how difficult that is, but how there is a glimmer of possibility.”

“We did not raise Zohran to be out of sight, out of mind,” Nair emphasized. “We raised him very much with what we were doing.” Frequent flights between Kampala and India and New York made her son familiar with planes from an early age. And because these seats were often paid for by Hollywood for work trips, they were sometimes in first class.

“So he’d be strapped into this big seat,” she said, “and he would see the seat-belt sign go off, and he would undo his seat belt. And he would waddle off in diapers and just vaguely say ‘bye’ to me. He would go down—this is no exaggeration—and lightly and politely give his hand to the adult on the aisle. But he would not look at the adult; he would look past the adult to see if there was a child there. If there was no child, he would go to the next row and do the same.” When he finally found a playmate, she said, she would watch Zohran’s diapered bum “waddle his way into the child’s seat,” where he would spend the rest of the trip playing with his found companion. Nair recalled one time when an amused flight attendant nudged her and said, “He’s going to be a politician.”

Click here to preview your posts with PRO themes ››

The critical success of Mississippi Masala meant, Nair said, that she had “avoided the second-film curse.” But her career got knottier after that. Despite her pride in never having missed a day of work, she conceded that “the pressure was building because I was balancing everything.” Mahmood bounced between visiting-professor posts in Durban-Westville, New Delhi, and Princeton. Nair was figuring out how to put together a film career in shifting locations, often far from the U.S. or India.

1994: With Zohran on the set of The Perez Family in Miami. Photo: Courtesy of the subject

1996: With Zohran in the New Delhi home of her mother, Praveen Nair. Photo: Gauri Gill

In 1994, she was hired to direct The Perez Family, about members of the 1980 mass boat migration of Cubans to Florida, starring Marisa Tomei and Anjelica Huston. “I loved the story of exile,” she said, “and have been inspired in so many ways by Cuban stories.” But as Pilcher recalled, “she was making a film embedded in Cuban culture” through a lens of social realism, while the studio “wanted a romantic comedy.” The Perez Family was a critical and commercial flop. Nair’s next project, Kama Sutra: A Tale of Love (1996), about a pair of 16th-century Indian virgins, was another disappointment.

In Cape Town, where her husband had recently taken a teaching job and was causing a stir with his proposed reimagining of the African-studies curriculum as the nation emerged from apartheid, Nair was teaching workshops in the Asian and Black townships about the Danish Dogme method of filmmaking, “where you learn how to make something out of nothing,” she said. She asked herself, “Can I do that for myself? I’m preaching it, can I live it?”

This was the origin of Monsoon Wedding, which couldn’t really be made from nothing: She needed financing. In the spring of 2000, Nair’s agent, Walker, suggested she travel to Cannes to pitch it to financiers and distributors. “I spent the weeks before Cannes lining up three days of appointments for us with the leading companies around the world,” Walker recalled. “A different meeting every hour for three days.” Nair flew from New York, where in 1999 Mahmood had been appointed director of the Institute of African Studies at Columbia. When she arrived on the red-eye, she met Walker in his hotel and he urged her to go up to his room to take a shower before the marathon of meetings. Twenty minutes later, she was back in the lobby: “‘Bart,’ she told me, ‘the film is financed.’” On her way upstairs, she’d run into the head of IFC Films and delivered a literal elevator pitch. He agreed to give her money.

In 2000, she shot Monsoon Wedding in an astonishing 30 days in New Delhi, casting friends and family members in a riotous, kaleidoscopic story about a big Punjabi wedding. The actors spoke in English, Hindi, and Punjabi, often mixing the languages in the same sentences. “If I went to a distributor, they would say, ‘Come on, how can we subtitle this?’” Nair said. “But I would say, ‘This is how we really are, and people will understand me. You just wait, they’ll get me.’”

They did. The film’s success led to bigger studio jobs, including a $50 million adaptation of William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair, starring Reese Witherspoon, and interest in her directing one of the Harry Potter installments, which her then-teenage son discouraged, arguing instead that she should direct the adaptation of Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake, which she did in 2006. “Zohran lived through all of this,” Nair said.

Mamdani told me he doesn’t remember exactly when he truly realized what his mother did for a living. When he was young, he said, he knew Pilcher and Taraporevala as “Lydia Maasi” and “Sooni Maasi” (the Punjabi term for maternal aunty) and only later “found out what they did for work.” He was 10 when Monsoon Wedding became a monster hit; he remembered watching it “and picking out all of the cousins and friends and my grandmother.”

He said, “It was around high school when I started to realize what everything meant.” The pinnacle came with Mississippi Masala. “When I watched it after graduating from college,” he said, “I struggled to both appreciate that this was one of my favorite films that I’d ever seen and that I would not exist without it. It would be enough if it was just one of those things. But it’s both.”

2026: With Mahmood and Rama at Zohran’s swearing-in ceremony. Photo: Laura Thompson/Shutterstock

If the new mayor seems preternaturally comfortable in the public eye, it’s because he actually has plenty of experience. There are photos of baby Zohran on Nair’s shoulder for the red-carpet premiere of Mississippi Masala. He scampered across the pages of national magazines, being described in a 2002 New Yorker profile by John Lahr as “Nair’s talkative doe-eyed son” who “exudes the charm of the well-loved” and appearing in the pages of New York to say FIFA and Sim-City video games were on his holiday wish list. When he was 15, Nair told The Believer about his teenage swagger: “When you call his phone, his voice-mail says, ‘Hi, you’ve reached the Ugindian president of the United States, otherwise known as the Brownest Man on Earth. He’s not here to take your call.’” Nair exclaimed with exasperated pride, “He’s talking about himself in the third person! I think, Zohran, please! You can’t do this. But they all love it.”

This exposure set him up as a child of privilege during his mayoral campaign, and he surely was in some ways. Though it is also a funny distortion, in a city powered by real-estate and financial magnates and their scions, to suggest that the son of a left-wing anti-colonialist Muslim academic and an immigrant female film director had unfairly leveraged his lineage to win the mayoralty. Mamdani attended a private middle school and enjoyed the luxuries of having one parent a celebrity professor at Columbia and another a regular recipient of Hollywood paychecks, but it is absurd to claim, as one Democratic strategist did, that Mamdani “grew up with three silver spoons in his mouth.” Nair joked, “My tax accountant called me up the other day and said, ‘I’ve been reading about your billions. Where are they, Mira?’”

The real wealth in the family was artistic and academic, which gave Mamdani access to the intelligentsia and its patrons. He is familiar to the kinds of people who write for magazines and newspapers (he once applied for an internship at The Nation and was rejected), the middle- to upper-middle-class culturati conversant with the officially moneyed and sometimes dependent on them: Directors who make films about homeless kids in Bombay don’t get to shoot multilingual pictures about their eccentric Punjabi family without funding extracted at hotels flanking the Croisette in Cannes.

“It’s never been easy to raise money,” said Taraporevala of Nair’s work, noting that Zohran has “watched everything” and learned from it. Nair, said Taraporevala, “has a fluency across classes and also across cultures. Zohran has that too.”

It’s the gift that enables Mamdani to reach the Commie Corridor and ensorcell Donald Trump. Discussing her son’s charmed encounter with the president, Nair said in December, “He doesn’t wear it on his sleeve, but he later told us how much he’d prepared for that.” Making something difficult look easy may also come from Nair, who told me one of her credos in movie-making is “Don’t show the struggle. My job is to make it look like I never had that struggle.”

“For people like me who come from other places who make New York our home, we’re constantly navigating between parts of our lives,” said the singer Ali Sethi, a Mamdani family friend and Nair mentee who first encountered her when he was an undergraduate at Harvard; he has since worked with her and performed at a Mamdani rally. “This is the corporate part, this is the ethnic part, this is family, this is my white friends, this is where my English has to be good. Major and minor, high and low, proper and improper, and public and private.” Both mother and son, Sethi said, have a gift for making these typically awkward navigations appear not only smooth “but irresistible.”

For all the steady attention they gave their son, Nair insisted that she and Mahmood “never helicoptered too much at all” and didn’t care about whether he traveled “the clichéd paths of success.” She said, “Really, the only thing we were concerned about was knowledge. He had to study the world. He had to read. He had to write.”

It’s possible, she conceded a little ruefully, that she might have “gotten involved with the college applications.” As Nair recalled, Zohran did not want to attend Columbia because he would have been taught by aunties and uncles. Also, despite his father’s position there, he did not get in. “But he applied to Harvard because I insisted on it,” said Nair. “Both of us had gone there. But I knew that you should go to a place like Harvard only if you absolutely want to go.” Zohran, apparently, did not want to go. “He did get into Harvard but with a gap year,” Nair told me. “But when he got the admission, he didn’t even tell me.” Mamdani had his heart set on Bowdoin College in Maine. “That was the only time,” she said, “that I was like, What the hell? But he wanted to do his own thing, which is great.”

Mamdani grinned puckishly recalling his mother’s interest in academic achievement. “When I ran for Assembly,” he said, “she wanted to know if I could do that with just a bachelor’s degree.”

“No, Mamma,” he assured her, “I don’t need a Ph.D. to be in the Assembly.”

Nair told me a version of this story too, insisting it had always been a joke: “I was imitating a bad aunty. I would say, ‘But Beta, what about your graduate degree? ’ ”

In her recollection, her 20-something son’s rejoinder was to call her “my fellow bachelor,” a reminder to Nair that she too possessed only an undergraduate degree, a fact, she confessed, “I totally had forgotten.”

Mamdani said that, when it came to his ambitions, he has always “felt their love, their support, their belief, and also that that has never translated into a reticence to tell me what they think or feel.” For instance, he noted, “when your son tells you they want to become an artist.” He paused for effect. “And then you check in at a certain point and say, ‘How’s that going? ’”

Here he was talking about his brief rapping career as Young Cardamom. Made with his friend Abdul Bar Hussein, Mamdani’s song “#1 Spice” (“Bring the flavor to the fish / Bring the flavor to the rice”) was featured on the soundtrack for his mother’s 2016 film, Queen of Katwe; in 2019, Mamdani released a solo track, “Nani,” about his grandmother Praveen (“I’m your boss, I’m your fuckin’ Nani / Got a doctorate, bitch, so don’t fuckin’ try me”) with a video starring the beloved Indian chef Madhur Jaffrey.

“Toward the end, I remember my father checking in,” he said. “How are the streams on SoundCloud? He didn’t say that, but that’s what I heard.”

Nair said, “I was happy to see that he didn’t pursue the rapping,” though she quickly added, “Of course, I loved the music.”

“I’ve never seen anyone work harder and never stop,” Nair said of her son’s mayoral campaign. In late December 2024, after Zohran and Rama celebrated their nikkah in Dubai, Nair said, “I remember so well that the next day he was on the plane. I said, ‘Zohran, who is going to work at Christmas in New York City? Don’t go. Stay with us. Take her away for a weekend!’” But he went anyway. “He never, ever once believed that we had done enough.”

She wondered at the start of the campaign, she said, “What does it take to assume this is even possible? ” But then she remembered being “told that it was impossible to do what I did. I did think, I made Salaam Bombay! at 30. And Mahmood made two books—one of them was required reading at Harvard—by the time he was in his late 20s.”

Still, she said, “it is an extraordinary thing in your own lifetime and in the lifetime of a young man to have this happen.” She also said he surprised her in many instances. “He amazed me with some of his lines in the debates because I’d never heard that in him.” For example, his insistence that his opponents pronounce his name correctly. “I never let anyone mispronounce my name,” she said. “If I go on even the biggest talk shows, I would say, ‘It’s not MY-ra, it’s MEE-ra NYE-er’ [like “fire”]. And I would guide Bill Moyers on down how to say my name.”

Zohran’s insistence, she said, was a “reflection of the point of view we have, which is that we exist. Learn to deal with us. Say my name.” This call for recognition was key to his electoral project. “The people in New York were not regarded as voters before,” said Nair. “Not just the Muslims but also the Bangladeshis. The Pakistanis. People have come back into this city to vote for him because they felt heard by him. They felt seen by him.”

Wasn’t this her own project as a filmmaker, her shtick, as she put it? Making people who’d gone unseen and unheard visible and audible? She considered this. “Yes,” she said finally. “I wanted to make these people at various levels visible. Yes. And here we are.”

Nair spoke with pride about being a “canvassing mom.” From January to June, she said, “I was there three days a week, canvassing different neighborhoods. And I saw how he went from being unknown to everybody liking him to exultation by May, and by June people were just waiting to vote for him.” When she’d walk the street, she said, “it was like beams of sunshine radiating at me, swear to God.”

She tells herself Zohran will do well. “If the campaign was any indication—and it was—of how he’ll run a government, which is with great originality, inventiveness, just plain love,” she said. Nair, who tells film students to “cherish their collaborators,” is reassured by the people he has hired: “I love the group he’s put together. He’s going to work with the best.”

She is also reassured, she said, by “his wonderful choice of wife. A strong woman, formidable, self-possessed, and just extraordinary.” Nair said she liked Duwaji immediately. “And I loved her art. That, for me, was a great relief. Because the human being is very good, of course. But you know, as an artist, to not love her art, I would die! But I really love her work, and I love her soul.”

At one point, I asked Nair if her father, who died in 2012, would have been excited by his grandson’s rise. She hurried to another room to retrieve a piece of art she had just brought back from India, given by her father to Zohran on his 3rd birthday. It was a painting of British India, including Pakistan and Bangladesh, before the partition that severed so many, including her own family, from one another and their history. Over the map is a painting of toddler Zohran and below it two inscriptions: “With love from Nana” (the Hindustani word for maternal grandfather) and “My friends will be these three, and of each other too.”

“It’s just amazing,” Nair said. “That my father thought that Zohru would unite these three countries. But you know what? When he started being an assemblyman who lived in Astoria, the Indians, the Pakistanis, and the Bangladeshis were his constituents, so Zohran actually became the assemblyman of this map. I mean, it was astounding. That is what my father wished for. And my God, he would be so amazed.”

Mamdani, of course, is a creature not only of Queens but of Manhattan. Nair likes to write about her movies’ production, and in an essay for a later edition of The Namesake, she wrote of how Lahiri’s novel crisscrosses worlds familiar to her: Calcutta, Cambridge, and finally New York. “Jhumpa’s New York is not the immigrant communities of Little India or Jackson Heights but the New York of lofts, Ivy League bonding, art galleries, political marches, book openings, country weekends in Maine with Waspy friends, a deeply cosmopolitan place with its own images and manners,” Nair wrote. “This was the place I had lived in since 1978; this is the city where I learned how to see.”

“I see the world I put him in,” Nair told me of her son, “as very much reflected in the multiplicity of what he does. There’s a real unity that can happen in multiplicity. And I think that he has exercised that in his campaign and in his thinking. It comes from some cloth that we cut together.”

Thank you for subscribing and supporting our journalism. If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the February 9, 2026, issue of New York Magazine.

Want more stories like this one? Subscribe now to support our journalism and get unlimited access to our coverage. If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the February 9, 2026, issue of New York Magazine.