This article was featured in New York’s One Great Story newsletter. Sign up here.

Can you handle 22 inches? asks a billboard in Orem, Utah, near exit 269 on Interstate 15. The question sits next to an image of Jessi Draper — local mother of three — lying on her back in a black minidress, chestnut hair spilling down toward the highway. Utah County, located about 45 minutes south of Salt Lake City, is nicknamed “Happy Valley” for its concentration of canonically nice, wholesome Mormons, who make up over 70 percent of the residents. A few miles north in Pleasant Grove is the home of JZ Styles, Draper’s salon-and-hair-extension empire, a low white complex nestled among strip malls and drive-throughs. “We like to call this Hair Candy Land,” Draper says as she shows me around a cavernous warehouse, where thousands of extensions, with names like Angel Food Cake (white blonde) and Cherry Cola (reddish brunette), hang like furry wallpaper.

It’s an unseasonably warm day in December; snowcapped mountains rise dramatically above the salon, but down here in the valley, some guys are wearing shorts. Draper, five-foot-two with giant blue doll eyes and waist-length highlighted waves, is wearing a green flannel shirtdress and knee-high stiletto boots. She clacks from the warehouse to the light-filled salon, where stylists sew extensions onto the heads of clients in UGGs and matching sweat-suit sets. “Everything is so crazy right now,” Draper, 33, says. By “everything” she means the deluge of attention, opportunity, and money that has transformed her life as a Utah mom and business owner in the past 15 months since she began starring in the Hulu reality series The Secret Lives of Mormon Wives.

In This Issue

Under the Mormon Influence

See All

Draper is not a practicing Mormon, having left the church in 2019. Four of the nine cast members say they are no longer active, and not all of them are currently wives. But they remain what one could call culturally Mormon: young, beautiful mothers living in Happy Valley with several kids apiece, some of whom they had as near teenagers. The show depicts their daily lives as members of MomTok, a loose confederation of Mormon and ex-Mormon stay-at-home moms who began making videos together in 2020. In March, Secret Lives will air its fourth season in less than two years; the third debuted as Hulu’s top-rated show, outperforming The Kardashians.

In the intervening years, Draper’s net worth has multiplied. When the first season aired, her salon sold out of six months’ worth of inventory in two days. She has trademarked “Utah Curls” so she can sell hair tools with the phrase emblazoned on their sides. Multiple women have moved to Utah, she says, to come to her recently expanded hair school. She even makes money as a landlord to the Secret Lives production company, which rents warehouse space to film confessional scenes. On the day I visit, a cluster of earpiece-wearing producers in black jeans and shirts sits under one of the walls of hair.

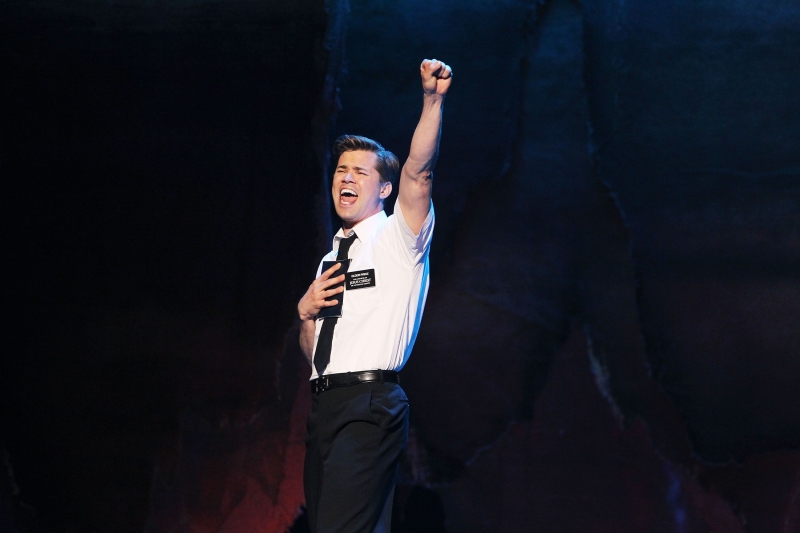

The last time the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints entered the public eye, it was 2011 and Mitt Romney was running for president. The monster-hit musical The Book of Mormon debuted on Broadway that year and turned the Latter-day Saints into a national punch line, indelibly shaping our image of America’s major homegrown religion. Its avatars for Mormonism were two naïve, repressed, perma-smiling missionaries. “Hello, my name is Elder Price and I would like to share with you the most amazing book!” one sings in the show’s opening number before going on to recite very real, very zany aspects of the Mormon faith. Among them: that, in 1827, the religion’s founder and prophet, Joseph Smith, discovered a new Christian scripture engraved on golden plates buried in a hill near his hometown in upstate New York. That the plates described a group of ancient Israelites who sailed on boats from the Holy Land to the American continent. And that the Garden of Eden was actually located in Jackson County, Missouri.

A few months after the musical opened, Romney was splashed on the cover of Newsweek, dressed up like The Book of Mormon boys, while his undergarments (what one New York Times columnist called his “magic underwear”) were the subject of constant late-night-TV ridicule. Meanwhile, Mormonism became synonymous with polygamy, a practice that the Latter-day Saints officially abandoned in 1890 but that persisted among fundamentalists, some of whom were notorious criminals, like Brian David Mitchell, Elizabeth Smart’s kidnapper. When they weren’t depicted as pedophiles, men with multiple wives appeared as narcissistic failed patriarchs, whether in fiction (HBO’s Big Love) or docuseries (Sister Wives, TLC’s plural-marriage reality show).

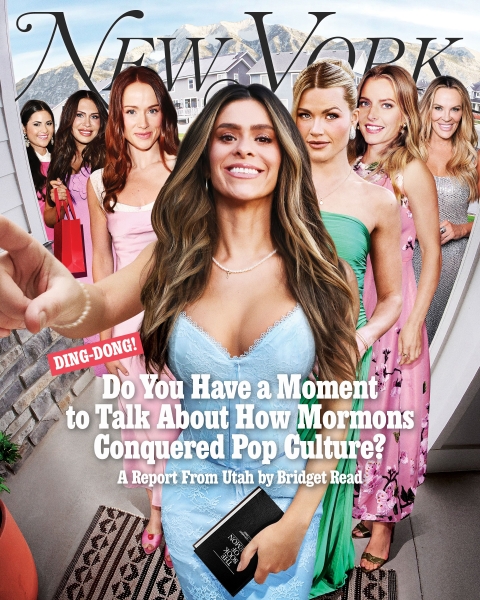

The representatives of Mormonism are no longer geeks in white shirts with name tags. Nor are they men at all. America is in the middle of a second Mormon Moment, and its representatives are women with flowing hair and flawless skin in outfits that certainly don’t accommodate official undergarments, if any. The stars of Secret Lives are only one element of a host of cultural exports from Utah currently taking off. They were preceded by the cast of Bravo’s The Real Housewives of Salt Lake City, another reality show about active and former Mormon women, and by Hannah Neeleman, a prominent Mormon farmwife and social-media powerhouse known as Ballerina Farm. These Mormon and ex-Mormon women, the makeup and clothes they wear, the red-light-therapy masks and blenders and blankets they use, and the protein powders, supplements, and sodas they drink have found an enthusiastic audience across the rest of the country. In entertainment terms, they have moved from TLC to Disney, from freak to niche to prime time: Next month, a Mormon woman, one of the Secret Lives stars, will receive that ultimate all-American girl-next-door imprimatur and become the next Bachelorette.

How did this happen? The Latter-day Saints believe in ongoing revelations from God; as a result, they can be both inflexibly doctrinaire and expansively open to change. It makes it hard to tell, nearly 200 years after Smith founded his insular church, whether Mormons have assimilated or we’ve become more susceptible to the pitch.

Clockwise from left: The Book of Mormon, 2011. Big Love, 2006. Sister Wives, 2010. Clockwise from left: The Book of Mormon, 2011. Big Love, 2006. Sister Wives, 2010.

Mormons settled in Utah en masse following an arduous decadeslong journey from Illinois after Smith was murdered by an anti-Mormon mob. Thousands of pioneers riding in wagons and pulling handcarts died of exhaustion, malnutrition, disease, and violence. So it feels intentional that the densest part of modern-day Zion can be covered breezily by car in under two hours on I-15. Roughly 80 percent of Utahans live in an urban corridor along the highway, nestled against mountains called the Wasatch Front. Trends spread fast. Multilevel marketing, the controversial practice that shares its origins with pyramid schemes, has flourished here. So has influencing, an industry Mormon women pioneered. One name is whispered among lifestyle influencers everywhere with the same reverence tech bros use for Steve Jobs: Rachel Parcell, a petite brunette and mother of three who lives in a ritzy town a few miles north of Pleasant Grove in the foothills of the mountains called Alpine.

Parcell was an engaged 19-year-old graphic-design student living with her parents when she launched her blog, Pink Peonies, in 2010. It chronicled what seemed to be her storybook Mormon life: Parcell, with her shiny dark hair, button nose, and dancer’s body, was always heading to church with her fiancé, Drew, a tall blond who woke her with a dozen roses on Valentine’s Day. Parcell trained for half-marathons and wove homemade floral headbands and prepared her mother’s berry salad. The couple’s wedding photos showed Rachel on a horse kissing Drew in a meadow. After she was featured on the cover of Utah Valley Bride, Mormon women all over the state started asking her for style tips. Then requests came from their cousins in Texas, Arizona, and Hawaii. “They would be like, ‘What skirt did you wear to the temple?’” Parcell recalls.

Mormonism’s mimetic culture, a keeping-up-with-the-Joneses competitiveness, is instilled in members from a young age. All Mormons are taught to demonstrate “worthiness”; only those deemed worthy can get married in a Mormon temple and live forever in eternity with their families. (The least worthy will spend a millennium in a temporary hell called “spirit prison.”) Starting at age 12, they are summoned to interviews with their bishops in which they’re asked about their spiritual commitment, good works, prayer, and chastity. This constant striving for worthiness creates a norm of community surveillance; at church-funded Brigham Young University, students are encouraged to report each other for honor-code violations like drinking or having premarital sex.

Only Mormon men can baptize, bless, prophesize, and join the church’s highest leadership ranks. For LDS women, being worthy depends first and foremost on the divine callings of marriage and motherhood. In both regards, Parcell was a model of perfection. “I looked up to Rachel,” says Draper, the Secret Lives star. She was beautiful but modest, devoted to her husband, and active in her church. When she started linking her J.Crew pencil skirts and Nordstrom dresses on her blog, a highly connected and mobilized network of Mormon women clicked through eagerly. Eventually, she got an email from RewardStyle, a new company that offered to help her make money through “affiliate links,” trackable codes that could get her a commission every time a follower bought something through her blog. She quickly made $1,000, then $5,000.

Within a year, Parcell had made enough to drop out of school. She became a power user on RewardStyle, now known as LTK (short for “Like to Know”), one of the country’s largest affiliate-shopping platforms. Parcell says she was the first influencer J.Crew ever paid a flat-rate fee — $10,000 — an early iteration of the now-coveted brand deal. After Instagram added its own affiliate-link feature, a “swipe up” button, Parcell started making thousands in commissions there too.

“The Utah bloggers were the first to drive commerce in a way we weren’t seeing with traditional street-style bloggers,” says Reesa Lake, a current LTK executive and Parcell’s former manager. The bloggers taking off in Los Angeles and New York were primarily going for high-fashion looks their followers couldn’t afford. Parcell remained geared toward her local Mormon-mom audience, posing in front of her garage or her front steps in affordable dresses and wedges. As she got older, her links expanded into homemaking and motherhood: When she and Drew built a new house, she posted custom distressed furniture and antique chandeliers. When she had her first child, she posted about the best strollers. “She could move product like nobody I had ever seen,” says Tan France, the Queer Eye star who lives in Salt Lake City and collaborated with Parcell in her blogging days. Parcell’s success enabled her to monetize far beyond the Google ads of the Blogspot era — it led to the development of the monetization engines themselves. How much an influencer’s followers will “engage” with their posts and buy what they’re selling is now the industry’s most important metric. Companies like LTK were inspired to collect more precise data, allowing Parcell’s agents to show brands exactly how much she could make them. Soon, others began following in her footsteps, including Mindy McKnight, an LDS mom with a hairstyle blog that she eventually parlayed into an enormous YouTube channel and product line, and Amber Fillerup Clark, whose hair-care brand, Dae, is now stocked by Sephora.

Mormon influencers are part of a long, rich tradition of LDS tech pioneers. In fact, the internet as we know it wouldn’t exist without them. In 1969, the University of Utah was a key part of Arpanet, the federal government’s Cold War–era computing experiment that became the modern web. Mormons invented one of the first word processors and created the world’s biggest online genealogical databases, including Ancestry.com. Every Apple computer’s operating system includes Deseret, the phonetic alphabet created by Brigham Young, Joseph Smith’s successor, because an LDS engineer proposed its inclusion in 1996.

Mormon tech enthusiasm is cosmological; Mormons are Christians, but they believe that human beings can ultimately become divine and commune directly with their Heavenly Father. The idea that one day all of human aptitude and knowledge might ascend to a manmade cloud jibes completely with their notion of the Second Coming, when the worthiest families will ascend to live forever in a celestial kingdom. (The church itself has invested heavily in AI, social media, and e-commerce: Ensign Peak Advisors, the LDS hedge fund, and other third-party funds manage a war chest estimated to be worth over $200 billion; its top stock holdings include Nvidia, Meta, Amazon, and Google.)

When Web 2.0 came around in the aughts, the evangelizing potential of blogging became clear to LDS church leaders, who each year dispatch thousands of young Mormon missionaries across the globe. Now, they could do it from their computers. In 2007, three years before Parcell started Pink Peonies, Elder M. Russell Ballard asked BYU Hawaii graduates in a somewhat infamous address to “join the conversation by participating on the internet, particularly the new media, to share the gospel.” He was asking them to go forth and blog.

When masses of highly educated, stay-at-home Mormon women flocked to lifestyle blogging as an expressive outlet, it worked because the activity didn’t take them away from their children. It required their children. And in their own way, they were helping spread the faith. Parcell’s mother once encountered a fan at church: “She came up to her crying and said, ‘I became a member of the church because of your family.’ Us prancing around on the sidewalks in our outfits” — Parcell laughs — “we were being missionaries.”

From left: The Real Housewives of Salt Lake City, 2020. The Secret Lives of Mormon Wives, 2024 From top: The Real Housewives of Salt Lake City, 2020. The Secret Lives of Mormon Wives, 2024

A decade ago, there was a ceiling on the Mormon mommy bloggers’ commercial appeal. They were too basic, too suburban, for the coasts. At one dinner during New York Fashion Week, Parcell recalls, the husband of another blogger loudly made jokes about Mormons. “I felt like that random Utah girl,” she says. “I was pregnant at the time.” In 2017, Parcell, her sisters, and her management company shopped a reality show around Los Angeles. “It was a kind of next-gen Mormon Kardashians,” Lake says. No one bit. France, who was also involved in the pitch, recalls one executive saying, “‘Oh, that won’t sell in Hollywood right now. We need somebody who’s not just a white girl.’ I said, ‘Well, it’s Utah. That’s probably not possible.’”

Then came the pandemic. “Family creators were always our bread and butter,” says Lindsay Nead, a talent manager who founded the agency Parker in 2017. But lockdowns created a mass onboarding event for mom and family content that previously had a reliable but niche audience. Now, the likes of Gwyneth Paltrow and Selena Gomez were posting from inside their houses, cooking for their families and cleaning their living rooms with their favorite products — just like the girls up and down the Wasatch Front. And the girls were cheaper, faster, and better at it. “With traditional production shut down, you were looking at people who had always been writer, producer, director, marketer, editor,” says Lisa Filipelli of Select, another digital agency with a roster of Mormon influencers, including McKnight. Filipelli has been representing her client Aspyn Ovard, a 29-year-old Mormon-raised blogger and mom, since she was 18.

Brands rushed in to commission Reels, unboxings, and hauls. After the summer of 2020’s mass protests against racial inequality, there was a pivot among corporate America to a category called “noncontroversial” families, Nead says. Companies like Walmart, Target, and Amazon clamored for personalities that had previously been deemed too vanilla: usually white, straight, and middle-class presenting. Not necessarily Christian, but not not Christian. “On the back end,” Nead says, these influencers were making “far and away more money” than their nonwhite counterparts. “They still do.”

It was around this time that the future stars of Secret Lives found one another in Happy Valley and online. They were recently married, postpartum stay-at-home momfluencers, fluent in the language of their foremothers — affiliate links, sponsored content. They posted their babies, their starter houses, and their activewear. Bored at home, a few of them got together for afternoon hangouts and began filming silly videos on TikTok. They christened themselves MomTok.

If the earlier generation sold worthiness, the new one reflected TikTok’s bent toward humor and candor. Like many Mormons, the women were great dancers. (Secret Lives star Whitney Leavitt made her Broadway debut this month in Chicago, and last year’s Dancing with the Stars winner, Witney Carson, is a Latter-Day Saint.) When they filmed videos, they noticed how stereotypically Mormon they looked: the long hair, the babies on hips. They realized they could skirt the line between “non-controversial” and “controversial” mom content and still get followers and brand deals by being frank and funny about Mormonism. They made jokes about “soaking,” a semi-apocryphal practice in which young Mormons have sex without breaking the covenant of chastity. Taylor Frankie Paul, the ringleader of the group, called herself a “mommy by day” in a shapeless white gown and a “mami by night” in a leather crop top. “Why did you all get married so young?” one video’s caption asks as Paul and her fellow moms gyrate. “So we could stay home and do nothing.”

In May 2022, Paul went live on TikTok to her millions of followers and revealed she was getting a divorce. She and other MomTok women had been “soft-swinging,” as in hooking up with one another’s husbands. Suddenly, the country was invested in the intricacies and hidden tensions of a Mormon marriage. “At the drop of a hat,” says Danielle Pistotnik, a Select manager who represents Paul and several other MomTokers, nearly every network wanted in. Select brought on Jeff Jenkins, who had produced The Kardashians, and made a deal with Hulu for a new reality show. To Pistotnik, also an executive producer on Secret Lives, the swinging drama was just the show’s initial hook. What made it stick was that America was finally ready to accept Mormon women. No longer did the idea of long-haired LDS girls conjure images of Warren Jeffs’s fundamentalist compound. They were immediately legible as hot-mom influencers. “As opposed to showing them in this dark, serious, docuseries way,” Pistotnik says, “you could be like, ‘Oh, they are just being girls in this place where you would not expect it.’”

Draper describes the church as “a background character” on Secret Lives. The version of the faith the stars do embrace on the show appears modern, flexible, and millennial. They discuss wearing and not wearing garments and the pressure LDS women feel to be perfect. In one episode, the cast attends a Pride event, publicly bucking the church’s stance on homosexuality. The stars routinely invoke “the patriarchy.” Layla Taylor, the sole Black cast member, discusses the racial prejudice she’s faced in Mormon culture. (Before 1978, Black Mormons could not fully participate in temple rituals, nor could Black men hold leadership positions.) Paul describes her faith as in flux: Her father blessed her newborn son in the Mormon tradition, for example, rather than the baby’s father, since he and Paul are not married.

The popularity of Secret Lives has created “the craziest ripple effect,” says Pistotnik, whose clients are turning down six-figure influencing deals. She can see other Mormon influencers getting a boost in online engagement when new episodes drop. Nead, the Parker founder, says her Utah-based clients, none of whom is on the show, are making no less than $250,000 in partnerships a year. One of them, Ashley Henson, 31, a blonde, svelte, newish influencer in Happy Valley, has triplets and two toddlers — five kids under 5. In December alone, she made $25,000 in brand deals. Multiple Secret Lives assistants are building their own followings doing “Spend the Day With Me” videos, grabbing their bosses’ lunch orders and unpacking their PR gifts. The market is verging on oversaturated. “There are so many of us,” one 24-year-old mom told me. “You go to one event and it’s like dropping food in a fish tank.”

The Mormon and ex-Mormon influencer ecosystem is in no small way supporting the state’s economy. Local businesses have shaped their operations to fit the texture of a stay-at-home, car-based mom’s daily life. HydroJug, a Utah company that previously focused on making a large water bottle with a straw for gymgoers, pivoted to a cupholder-friendly, spillproof 40-ounce container for moms on the go in 2023. It is now far and away the best-selling item. At Swig, Utah’s first and largest “dirty soda” chain, the storefronts are drive-throughs, staffed by a militia of teen girls, where customers can add syrups, creams, and other flair to their 32-ounce Dr Peppers and Diet Cokes. Swig CEO Alex Dunn (a former deputy chief of staff to Mitt Romney) describes his customer base as “busy young females” looking for “something to help get them through the day.” Influencers regularly post themselves ordering from their cars between school runs and errands. These deals have paid off beyond Utah: Swig experienced 43 percent growth in 2025, with 136 locations throughout the United States. There’s a dirty-soda copycat in Rockefeller Center.

Click here to preview your posts with PRO themes ››

Blogging took off among Mormon women in part because of the isolation of motherhood; enterprising millennial mothers have now monetized every element of their atomization. In many cases, they’ve used the profits to liberate themselves. “My business has doubled,” says Kenzie Bates, an event planner who has put on many of the Mormon Wives’ baby showers, birthdays, and holiday parties. “I left a very Mormon, very controlling marriage.” Many of the currently married husbands of the Secret Lives stars have stopped working. Some now work for their wives.

If one aspirational vision of Mormon and Mormon-adjacent motherhood is suburban women girlbossing from their phones, Hannah Neeleman represents an opposing one: an off-the-grid, back-to-the-land agrarian fantasy of the frontier. Neeleman, 35, and her husband, Daniel, are an LDS couple who married requisitely young and bought a farm together in Kamas, a former agricultural region near Utah’s ritzy ski resorts, in 2017. They named it Ballerina Farm, after Hannah’s former dancing career; born and raised in Utah, she met Daniel while she was attending Juilliard. Daniel, the son of David Neeleman, a prominent Mormon multimillionaire and the founder of JetBlue, was raised in a mansion in New Canaan, Connecticut.

Hannah Neeleman on the cover of Evie, 2024

Neeleman, like Parcell, started her posting career on Blogspot with a site called We Took the Train in 2013. Her early blogs are a less-polished version of Parcell’s Pink Peonies, documenting baking with her kids, going to church, pregnancies, and holidays. Over the years, she has amassed more than 20 million followers on Instagram and TikTok, all while building out the farm operation and an e-commerce business with Daniel and giving birth to eight children. The Neelemans are press averse, but they have spoken openly about their classically divided and devout Mormon household. Hannah’s blog linked directly to the church’s website, and her current content makes traditional motherhood — predominantly cooking homemade meals for her giant family — look beautiful and joyful. She was labeled “Queen of the Tradwives” in a 2024 profile in the Times of London.

Tradwife, however, is an imprecise term. It’s been applied to Evangelical Christians who say women should never work and to Neeleman’s friend Nara Smith — a working model married to fellow model (and Mormon) Lucky Blue Smith — who makes homemade Goldfish while wearing eveningwear. Yet Neeleman’s content doesn’t advocate 1950s-style housewifery in the same way some tradwives do — not exactly. What Ballerina Farm is advertising goes further back, to the homesteading era — more Yellowstone (parts of which filmed in northern Utah) than Leave It to Beaver. In her farmhouse kitchen, the fridge and the dishwasher are hidden, creating the illusion that the farm is preelectric. In modern terms, her philosophy skews MAHA, a movement that has found legislative support in Utah with fluoride and red-dye bans; Ballerina Farm’s marketing emphasizes clean living and freedom from the vaguely defined menaces of big ag and big food. The farmers drink raw milk — though the Neelemans stopped selling it after state health inspectors found high levels of bacteria in some samples.

When I arrive at the farm, about an hour east of Happy Valley, no representative will answer questions. A member of the roughly 100-person team gives me a tour. I’m told it’s the first new dairy in the area in about 20 years. There is a state-of-the-art robotic milker, behind which the cows (who sleep on waterbeds) line up calmly like cars at a drive-through. Like her pioneer Mormon ancestors, who irrigated the Utah high desert nearly 180 years ago, Neeleman’s mantra is self-sufficiency. In 2020, she compared herself to “the champion farm wives of yesteryear.” “I strive to be a good homemaker. I want to put food on the table that makes my children happy and keeps my husband giving me the wink,” she wrote. “Hungry bellies leave jobs undone and I make sure my crew is fueled with God-given nutrition.” Even Ballerina Farm’s influencing operation is stubbornly independent; Neeleman doesn’t usually do sponsored content for other companies. She is almost always promoting her own products. The farm does, however, work with an ocean of influencers and affiliates, which post about its products. (A month after my visit, the company hosted its first “brand trip” for its top TikTok sellers.)

Last summer, the Neelemans set up their first retail shop in Midway, a town a 30-minute drive from Kamas, where you can buy their farm products and other curated housewares in person. Midway, with its Swiss-inspired, gingerbreadlike houses, was already known to tourists heading to ski at Park City or Sundance, but Ballerina Farm turned it into an international destination. “Every Friday when we’re walking the dog, we see a Sprinter van filled with blonde Mormon women get dropped off on the side of the street and beeline over to the Ballerina Farm store,” one local says. Exactly what you can buy that comes from the farm itself is a mystery. Not all the meat it sells comes from its own cows. Some is sourced from “select partner family farms” and some is merely “raised in the USA,” according to the website’s fine print. The same goes for the produce on its shelves, despite being sold in the same bespoke Ballerina Farm packaging. A member of the public-relations team tells me the company “supports other local businesses” in the area by selling their products.

None of this matters to the bottom line. At the store in Midway, groups of women, some with long hair and babies, some with short hair and no babies, gush over the handmade wax candles in the shape of fruit and vegetables, the wooden egg racks from England, the gingham table linens. The company won’t share its revenues, but it’s rumored to have made $70 million in profit last year. It has annexed more land from the state, purchased a local creamery, and is planning an agrotourism complex. Though Neeleman is outnumbered by the influencers of the Wasatch Front (it’s easier and cheaper to film yourself buying a dirty soda than it is to winterize a barn), she may be more influential, given the sheer reach of her personal brand. The Neelemans appeal to homegrown Christian traditionalists and would-be homesteaders with a reverence for preindustrial Americana, but there is clearly a diverse and wide audience for the Ballerina Farm aesthetic. Many people outside Utah are buying its vision of an unplugged, uncontaminated nuclear family (even if Neeleman posts every day). The company reports one of its biggest markets for e-commerce is Los Angeles. A majority of its social-media followers are overseas.

Back in the suburbs of Salt Lake City, in a strip mall with a Dollar Tree and a mattress store, is the final stop on my influencer pilgrimage: Beauty Lab + Laser, a med spa owned by Heather Gay, a cast member on Bravo’s The Real Housewives of Salt Lake City. Inside the white, bright spa, filled with women in sweat suits holding HydroJugs, a blonde, tanned Gay greets me happily in leather pants, stilettos, and a company sweatshirt. Before I can greet her back, two women walk in the door wearing T-shirts bearing the catchphrase of one of Gay’s co-stars. “We’re coming from New York City for my wife’s birthday,” one enthuses. “We got a dirty soda and came right here.” Gay gamely poses for a photo and plies the fans with Beauty Lab merch. As we look at the spa’s licenses, displayed next to a painting of Kim Kardashian’s ass, I tell Gay that producers pay Draper to rent out her space. “The Hulu girls get everything,” she jokes. Housewives debuted in 2020; Bravo was about to air its fifth season when Secret Lives premiered. Some of the Secret Lives stars used to come into Beauty Lab for treatments, but Gay says she has heard that Hulu will no longer allow it: “They don’t want the crossover.” (Hulu says there is no such ban.)

Gay, 51, and her co-founder, Dre Robinson, a brunette with luminous skin wearing, today, a hot-pink blazer, took over the spa from a plastic surgeon in 2016. They were both, back then, personae non gratae in Salt Lake society: divorced women. Robinson’s parents are old-money friends of the Romneys. Gay was married into veritable LDS royalty. Her husband’s grandfather Frank William Gay was a member of the so-called “Mormon Mafia,” a group of LDS men who oversaw Howard Hughes’s fortune during his reclusive final years. Gay’s in-laws were so Mormon and patriotic, she says, “my husband’s grandpa wanted to be buried with a giant Liberty Bell outside of the casket with a rope going inside, so for the Second Coming he could ring the bell and Jesus could find him. And the bell had a bald eagle on it.”

Before her divorce, Gay was a self-described perfect Mormon wife and mother. Full of creativity and ambition, she sublimated her desires for a bigger life into a photography side hustle. “It felt like a way to be a performative mom, you know?” Gay says of staging engagement shoots and family Christmas cards. “But really it was to feed my soul.” When she and Robinson started their med spa, they turned to the Mormon mommy bloggers, who by then had successful influencing careers. “Our business was built on our friends,” Gay says. They came in for Botox and lip injections, and as the bloggers made money, so did Beauty Lab; by the time the Housewives producers came by, in 2019, the operation was worth about $10 million. The show focused on Gay and some of those influencer customers in their roles as local businesspeople and socialites, rather than as mothers. They were all in their mid-to-late 30s and 40s. Since getting on TV, Gay has lost 30 pounds on GLP-1’s; over the years she has undergone more than $200,000 worth of cosmetic surgeries and treatments. A huge number of local businesses, like Beauty Lab, now cater to the influencer’s aesthetic needs: cosmetic dentistry, breast augmentation, spray tanning. Salt Lake City reportedly has more plastic surgeons per capita than L.A.

Gay started out on Housewives as lightly critical of the Mormon church. Gently, and with humor, she broke the rules: drinking on-camera, looking for a one-night stand. But over the past six years of its run, she has become an outspoken LDS detractor, publishing two memoirs that describe the religion as chauvinistic and stultifying. Lately, she’s begun calling it a full-blown cult. This past November, she released a limited docuseries on Bravo, Surviving Mormonism, which shows her confronting some of the darkest issues in the church: conversion therapy, sexual abuse, and the internal reporting system for that abuse, in which mandatory reporters are often patched through directly to LDS lawyers rather than the police. It makes her one of the sole naysayers in the current wave of popular Mormon content creators. Gay may be beloved by fans flying in from New York, but her old community, she says, shuns her. It’s surreal to watch young influencers become the hot new faces of Mormon motherhood when her 20s as a mother were some of her worst years: “My ‘secret life’ was a warm bottle of vodka hidden in a drawer.”

To Gay, there is little daylight between Ballerina Farm and the women of MomTok. She worries that even the spectacle of those divorced moms dancing, drinking, and talking about breaking the patriarchy tips into propaganda for the church — or at least aids in its lionization of young motherhood and the nuclear family. The organization can benefit from the rebrand without changing its core practices. That the church recently updated garments for women to include a thinner tank-top strap, something the faithful had long clamored for, exemplifies this, Gay says. It’s merely a cosmetic move, one that ultimately reforms nothing. “The whole world is supposed to lose their minds because a hundred-year-old man told us that we can show our shoulders now?” she asks. “It’s still a theocracy.”

She points out that the LDS church sued to prevent her from using the phrase “Bad Mormon,” the title of her first book, in promotional material. But it has taken no similar action against Hulu. (The Church has a trademark on the word Mormon.) “The top line looks positive and appealing with blonde, beautiful girls that are married and having babies. Maybe they’re emerging from the water in skintight white, wet dresses” — as the Mormon Wives do in the show’s intro sequence — “but a lot of them have bellies and they’re married and they’re having kids. It’s sexy Norman Rockwell, but it’s still Norman Rockwell.” The show is so seductive in its depiction of the life of a Mormon mom, she says, “I think to myself, Was it all so bad? ”

Gay wants to take me to see the temple she used to attend, not far from Beauty Lab. On the way, we stop at her house, a red-brick Insta-perfect McMansion on a tree-lined block she bought for nearly $3 million in 2023. Gay sees it as a symbol of her emancipation: “I used to take pictures on this street for my little housewife side hustle.” One of Gay’s daughters is home from college, and inside, on the kitchen counter, there is a Costco pie Gay bought for her. “See, I still got it,” she winks.

Her daughter has started to become an influencer herself. Gay has complicated feelings about this. “She has her own apartment in Miami, and she does TikToks where she opens her Keurig and does it all,” Gay tells me back in the car. “The other day, she said she was in her ‘tradwife era.’ And I was like, ‘What?! This is the thing I tried to get away from!’” She bangs on the steering wheel for emphasis. Gay’s mother was the ultimate worthy Mormon woman before any of it was monetizable: “She was an artist. She walked in snow in the blizzard of ’82 to pull home a dollhouse that she had hidden at a friend’s house for Christmas so that we six kids wouldn’t find it. Her friends were doing the same thing. And I wasn’t a mom, so I didn’t understand the backbreaking work behind that type of curation.”

We drive up to the white-spired temple at the top of a sun-drenched grassy slope. We’ve stopped for coffee on the way, and when Gay and I get out of the car, we’re walking around with our cups. “This is, like, rogue behavior,” she whispers. She hasn’t been back to a temple since leaving the church in 2019. “You need a barcoded card to get in,” she says. We walk around the front to see if there is a visitors’ center. On the front lawn, a couple is posing for wedding photos. Clusters of girls walk around with wet hair — “baptisms for the dead,” Gay says. Everyone is carrying a duffel bag for their temple garments, white sacred clothes that members wear for sessions — “three hours of chanting, hand signals, secret handshakes,” as Gay describes them. She remains outside in a pair of sunglasses while I walk through the entrance, which looks like a hotel lobby. Two men and two women in pristine white suits and skirt suits with name tags stand sentry in front of the double doors leading into the rest of the building. “Hello,” I say. “Do you have a visitors’ center?” They are smiling, but they shake their heads.

No representative of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints would tell me what they make of this second Mormon Moment. Whether the church pays influencers directly was the subject of a recent online controversy after an ex-Mormon influencer claimed a third-party marketing firm solicited her to film pro-LDS videos. One LDS influencer, Jasmin Rappleye, a Happy Valley mom who posts educational content about the faith, tells me she is funded by ads and LDS nonprofits. The church leadership is at least supportive of influencers’ efforts, if not bankrolling them outright: Last year, a group of influencers attended an official LDS event and posted about it on Instagram. “Elder Stevenson said that ‘influencers’ can be SUNBEAMS for HIM!!” one wrote. The church recently announced a new group of leaders had been appointed to be advisers for young men; four were YouTubers.

Rappleye’s own engagement has gone up with the virality of the Mormon Wives. “It’s really exciting to be part of this larger moment right now,” she says. The show doesn’t feel as mean as The Book of Mormon. “I don’t see it as deliberately trying to villainize the church. It’s like the old cliché that all publicity is good publicity.” Although Utah’s church membership has declined since 2020 from 60 percent of residents to just over 40 percent, BYU enrollment was up 15 percent over the past two years. In 2025, the Church claims it saw the highest number of convert baptisms of any 12-month period in its history, though this data is not yet publicly available.

The contradicting visions of Mormonism right now are perfectly suited to a country in the middle of an identity crisis. Its sister saints can be feminists or tradwives. They are moving us forward and taking us back. We can be sure that the church will benefit regardless. The Latter-day Saints have canny investments, starting with a direct stake in the success of its flock: Members in good standing are expected to tithe 10 percent of their annual income to the Church. That’s potentially 10 percent of Ballerina Farm’s empire of sourdough starter and colostrum protein powder and of the brand deals of the faithful Mormon Wives (even if they go to Pride). Beyond that, some of the companies owned by the oldest and most powerful Mormon families are invested in the products influencers are selling: Swig, the dirty-soda brand, is now owned by the Larry H. Miller Company, which belongs to one of the wealthiest Mormon dynasties in the state. A primary investor in Cozy Earth, a bedding company frequently posted about by the Wives, is a venture-capital firm founded by members of the Mormon Huntsman family, who are also invested in hair extensions. As more homesteaders come to Utah to pursue their Ballerina Farming dreams, as more hair-stylists attend Draper’s school, the church will benefit via its many real-estate and commercial ventures. It is the country’s fifth-largest private landowner. Even if it loses more of its official membership, as long as Mormon aesthetics and concerns — motherhood, beauty, perfection, worthiness — continue to appeal to industrious women everywhere, the institution stands to profit.

After I left the Jordan River Utah Temple and dropped Gay back at Beauty Lab, I drove to the Salt Lake Temple, LDS headquarters, which has been undergoing renovations since 2019. The church has been on a construction tear in the past few years, announcing 14 new temples around the world in 2025. The Latter-day Saints are building as if there is a coming boom. Families milled around the central campus, a sparkling-clean combination of the National Mall and Disneyland, looking at Nativity displays and Christmas lights that twinkled as the sun went down. “When does the temple open?” one couple asked two young missionary women in long skirts and sensible shoes. “Next year,” they said. “We can’t wait.”

Thank you for subscribing and supporting our journalism. If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the February 9, 2026, issue of New York Magazine.

Want more stories like this one? Subscribe now to support our journalism and get unlimited access to our coverage. If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the February 9, 2026, issue of New York Magazine.