Editor’s note: This story first appeared in New York’s issue of September 23, 1974. In Barry Diller’s recent memoir, Who Knew, he reveals that he was an unnamed source for the writer, Andrew Tobias, and describes the published article as “far more scathing and consequential than I could have imagined.” Diller, just 32 and working in television, was appointed CEO of Paramount almost immediately after it appeared, and Yablans was out a few weeks afterward. You can read another portion of Diller’s book, about his relationship with Diane von Fürstenburg, here.

A sampling of the cast, for flavor:

Charles Bronson, as Paul Kersey, is setting himself up to be mugged in the park. When the muggers approach (time after time), he blasts them.

Dino De Laurentiis has produced this movie, which he calls “Debt-a-Weeesh.” He has spent much of the week trying to get three full-page ads for its July 24 opening out of

Frank Yablans, our hero, or at least our central character, who is, make no mistake about it, president of Paramount Pictures. The name is ya-BLAHNS.

Rex Reed has seen Bronson plugging muggers in the park and thinks Death Wish is “terrific.” Yablans quips that this means Rex must think the movie was produced by

Bob Evans, the head of Paramount’s Hollywood studio, who is Frank Yablans’s employee, close friend, equal partner, archrival, nemesis, or imminent successor, depending on whom you’ve been talking with. Both he and Frank, like the Corleone boys, are vying for the approval of

The Mad Austrian, sequestered on the 42nd floor of the Gulf+Western Building, in the chairman’s office — cradling a tomcat in the crook of his elbow, we like to think, with his back to the camera and his eye on the stock market. This man, Charlie Bluhdorn, ran Paramount single-handed for a while after Gulf+Western bought it in 1968; Frank Yablans, though he still talks with Charlie every day (and, we’re told, does a sensational Bluhdorn imitation), has managed to beat the boss back to a largely supervisory role.

The Shark, co-starring with Richard Dreyfuss in another company’s upcoming movie version of Jaws, figures into our own script only to the extent that his mechanical malfunctionings are apparently holding everyone up on Cape Cod well beyond schedule, which means that Dreyfuss won’t be around to promote the opening of The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, which — like Death Wish, Chinatown, Parallax View, Gatsby, Sonny Carson, Daisy Miller, The White Dawn, The Conversation, and The Longest Yard — Paramount has out in first-run engagements this summer. (Also: Captain Kronos: Vampire Hunter and Frankenstein and the Monster From Hell.) No other movie company comes even close. Frank Yablans says his competitors would have been much better off if The Shark had swallowed The Dolphin and died of indigestion, and neither picture had been made. Not to mention a certain seagull Frank prefers not to mention.

Frank Yablans can be very funny, very charming, in a tough sort of way, when he wants to be. With me around, he wants to be. Maybe he should have me around more often.

Photo: New York Magazine

CUT TO: A conversation I had with Ted Zephro, until last October one of Frank’s right-hand men. “I wonder,” I asked Zephro, “whether Frank acts natural with his staff when a reporter’s around.” (Who can, after all?) “Was he pleasant?” Zephro asked back. “Very.” “Then that wasn’t Frank.”

CUT TO (this is how movie people talk — “cut to”): An executive staff meeting I was allowed to attend. Frank is in good form. As the meeting is breaking up, out in the hallway, I overhear some of Frank’s people asking each other — “What’s got into Frank? Why’s he in such a good mood?”

Frank can be pleasant, does have a warm, boyish side — but he doesn’t display it very often to people less powerful than he. Where some chiefs run their team of executives like a benign high school coach, from the sidelines, knowing the guys will perform because it would kill them to let him down, Frank runs his team like the star player, which he is, knowing his guys will perform because if they let him down, he would kill them. He is in on every play, down to details like schedules in Buffalo or whether to have comment cards at a sneak preview in Houston.

“Norman,” he says to rotund, beleaguered, lovable Norman Weitman, general sales manager, who has just returned to a meeting with some statistics Frank wants, “are you planning to go down to Houston for the Longest Yard preview?”

“No.”

“Well, plan on it.”

“Okay,” says Norman resignedly — picture Zero Mostel in the role — “I’ll plan on it.” I would give my Gatsby Teflon frying pan to know what dinner conversation is like evenings when Norman gets home from work.

“Are there going to be comment cards at the screening?” Frank asks.

“Bob Aldrich [the director] doesn’t want them,” someone volunteers.

“Well, I want comment cards,” Frank snarls.

“Okay, we’ll have comment cards.” And so it goes. One minor movie mogul calls Frank “the head of distribution who also happens to be president of the company.” But it works. Since taking over, Frank has simplified things. There are fewer executives, they work harder, they work together, and they work for him. He himself works entrepreneurial hours and is very good at what he does. I personally would hate to work for him (“And after this ax job, you prick, you never will” — I can hear him saying that, just that way), but I wouldn’t mind investing in one of his projects. I’m not saying he’s a genius or a superman or anything so romantic — but he’s good.

_

FADE IN: The executive conference room of Paramount Pictures on the 33rd floor of the Gulf+Western Building. A shiny white-and-blue sailfish, looking decidedly out of its element, arches across one long wall; opposite are two Godfather posters in cheap wooden frames. Frank is screening a sales film that will be used to introduce a new photographic process Paramount controls.

Yablans — like Paul Newman, Dustin Hoffman, Al Pacino, Tatum O’Neal, and, yes, Robert Redford, and, for that matter, Ted Ashley of Warner Bros., Roman Polanski of Chinatown, and Abraham Beame of New York — is short. (Unlike these people, he has designed for himself a split-level office which gives him a six-inch head start.) He dresses Brooks Brothers safe, perhaps not yet entirely secure in his movie mogul role. Only five years ago, when he joined Paramount, he was “assistant general sales manager.” Like Barbra Streisand, Woody Allen, Bobby Fischer, Bernie Cornfeld, Isaac Asimov, and Abraham Beame, again, Yablans is one of those lower-middle-class Jewish kids from Brooklyn (Williamsburg in Frank’s case) who made it to the top.

The sales film, very clever, runs for a few minutes showing how, with “Magicam,” real-sized people can perform on dollhouse-sized sets. The actor is actually photographed on an empty set, with one or two life-size props to give him his bearings; meanwhile, another camera superimposes the miniature set, in sync with the first camera. Also very clever. The idea is that miniature sets are cheaper to construct than real ones, and the Magicam process allows for special effects. Frank suggests they add a segment with a set of the Oval Office, and a Nixon impressionist making a speech. As he’s talking, Frank says, a giant hand should reach down and discard one piece of furniture after another, and then, when the set is bare, remove the president as well. This improvement is agreed to.

MAGICAM EXECUTIVE, speaking to Frank as the film ends: We added this tag for you, sir. It’s not on the other copies of the film.

ANNOUNCER ON FILM: Ladies and gentlemen, it is now my pleasure to introduce the president of Paramount, who wishes to relate his feelings about the Magicam process.

PURPORTED PRESIDENT OF PARAMOUNT (because, make no mistake, Frank Yablans is the president of Paramount), doing a full-scale Brando/Godfather imitation: My friends … I truly hope … that through this demonstration today … we have communicated to you … the fact … that Magicam is indeed a revolutionary innovation … If, somehow … despite of our efforts … we have failed to convince you … then what can I say … except from the bottom of my heart … f– – – you!

The Magicam executive hastily reiterates that this tag is not on the copies for outside distribution, but Frank loves it. “You have to use it! It’s terrific! In the first place,” he laughs, “this has become Paramount’s trademark: ‘If you don’t like it, f- – – you!’”

Such is not the trademark of a weak company, and it must be no end of satisfaction to Frank that the weak company he took over in 1971 is now perhaps the strongest company in the movie business. This summer Paramount had more prints out in the field, they say, making more money, than any company has had since “the golden days of Hollywood.” Onetime TV rights to The Godfather were recently sold to NBC for $10 million, doubling the old TV record. Godfather II opens at Christmas. And beyond that there are hoped-for “giants” like The Day of the Locust (Easter), The Last Tycoon (about Thalberg’s last days at MGM), Marathon Man (from William Goldman’s not-yet-published novel), Six Days of the Condor (Redford), and even “Project X,” which is the proposed “Walter Winchell Story,” starring Bob Hope.

Photo: New York Magazine

There will also be more bombs, of course, à la Jonathan Livingston Seagull. The Little Prince, scored by Lerner and Loewe and opening for Christmas at Radio City if it doesn’t have to be scrapped altogether (Nelson Riddle may be hired to reorchestrate it), is likely to be the next little disaster. But at Paramount the profits on the Big Pictures have more than canceled out the occasional losers, in part because pictures are kept to relatively modest budgets. Paramount profits grew to $38.7 million in 1973, or 22 percent of Gulf+Western’s total, on sales of $277.5 million. This suggests that Frank has done a great job. (It doesn’t prove it, mind you, but there is that suggestion.) It also puts him in a position of substantial power. He likes that.

What he doesn’t like is all the publicity his friend and studio head, Bob Evans, has been getting. In the last month I’ve told several people that “I’m doing a piece on the president of Paramount Pictures.” “Bob Evans?” they ask. So it has been extraordinarily easy to get Frank to agree to this story.

_

QUICK TAKE: Lunch at ‘21.’ Three of Frank’s publicity honchos are pitching a Newsweek staffer who says Bob Evans is being considered for a Newsweek cover. The purpose of this caviar-and-Champagne luncheon, courtesy of the shareholders of Gulf+Western, is to persuade him that Bob Evans doesn’t deserve to be on the cover of Newsweek — Frank does. (Neither one, to date, has made it.) Le tab: $245.

_

FADE IN: Frank’s northeast-corner office, magnificent view, gold Godfather Oscar sitting by the multi-buttoned phone. Frank has a button for each of his key people. When their phones buzz, they know it’s he. Frank also has a button that automatically shuts the door to his office (“It must have been the wind”), another for the door to the adjoining private john, and, of course, a button for each of the drapes.

Frank is meeting with three Canadians whose The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz is opening in a few days. It is the story of a Jewish cabdriver’s son — Frank is himself a Jewish cabdriver’s son — who fights his way out of the ghetto and into a three-piece suit. He is insanely energetic, likable, and full of impish fun. But he is also fiercely motivated, selfish, conniving, ruthless, and calculating. He does what he has to do to get his way. Bob Evans is credited as having been the first of many to subtitle this film “The Frank Yablans Story.”

The Canadians are asking Frank to downplay the fact that this is a Canadian film. Agreed. Frank is advising them to play down the Golden Bear award the film won at the Berlin Film Festival — you don’t want to give the film an auteur image, Frank says. Agreed. The Canadians want to know why the film is opening on a Wednesday. Because, Frank explains, he recently discovered that the original scheduling would have had four Paramount releases opening on the same day. He has ordered them spaced apart so that each will get more attention. Who at Paramount, the Canadians want to know, should they “lee-ayse” with? They should “lee-ayse” with him, Frank explains wryly, or else they won’t get any answers. Frank pauses to read a note that is carried in to him, and, annoyed, responds defiantly — “Tell him I will not be up ‘in five minutes.’ I will be up when I finish my meeting.” CUT To a tomcat being stroked in the crook of an unidentified elbow.

The Canadians are asking why Duddy (which rhymes with “goody”) is opening at the Forum, a Broadway theater, as well as the Baronet. Aren’t Broadway audiences less sophisticated than Third Avenue audiences? “That’s bull- – – -, That’s bull- – – -,” says Frank, who estimates that opening-day gross at the Forum will be $5,400. Frank explains that when he opened Chinatown on Broadway along with Third Avenue, “my partner Bob Evans was sucking his thumb in the corner for a month.”

But — Frank pulls out the exact figures — Broadway outgrossed Third Avenue.

Frank buzzes.

“Yes, Frank?”

“Bring in the schedules on Duddy Kravitz.”

Norman Weitman comes in with the schedules on Duddy Kravitz. Frank doesn’t like them, and changes them. Norman had the schedules at the two theaters staggered, but Frank doesn’t want the last show to start any later than 10:30 p.m., even if it means cutting back from six performances a day to five (which it does). It is too late to change the Sunday Times ad, but Monday’s will be changed. (Anyone who used Sunday’s ad and arrived to find the late show already half an hour gone will now understand why it would have done no good to complain “right on up to the president of the goddamned company, if I have to” — because it was the president of the goddamned company, if you can believe it, who adjusted the time half an hour.)

“How well will the film do?” the Canadians want to know. Frank, who has been relishing his older-wiser-and-vastly-more-powerful role in this meeting, tells them that “the film could do $10 million.” Dramatic pause. “Or it could do $1 million.” He tells them, “Face it — it’s a flawed film. It’s a flawed film.” He pauses just long enough for the blood to begin burning their cheeks — “but every film is flawed,” he says. Relief. Frank says he has high hopes.

Finally, the Canadians hand Frank “a very hot property” they would like him to read. Without even looking at it, he tells them, “I’ve read it. I turned it down two months ago.” But … but … And indeed Frank has read it: He’s well plugged in, he knew what they’d be bringing him, and he does his homework.

But lest we come away quite as awed by Frank as the Canadians seemed to, it should be noted that opening-day gross at the Forum, as it turns out, was $809. After running there ten days, Duddy was moved to the Little Carnegie, which, some say, plays to a more sophisticated audience.

_

If Frank isn’t a certified oracle, he is nonetheless persuasive. And if he takes himself very seriously — he has political ambitions and is convinced that becoming a congressman would be “no problem” — he also has the ability to laugh at himself. “The thing I found so amazing,” recalls Peter Maas, author of Serpico, of his first encounter with Frank, “is that I walked into his office determined that I wasn’t going to go with what he wanted [a snake coiled around a nightstick on the cover of Serpico — Maas hates snakes] — but within five minutes I just didn’t have any answers.

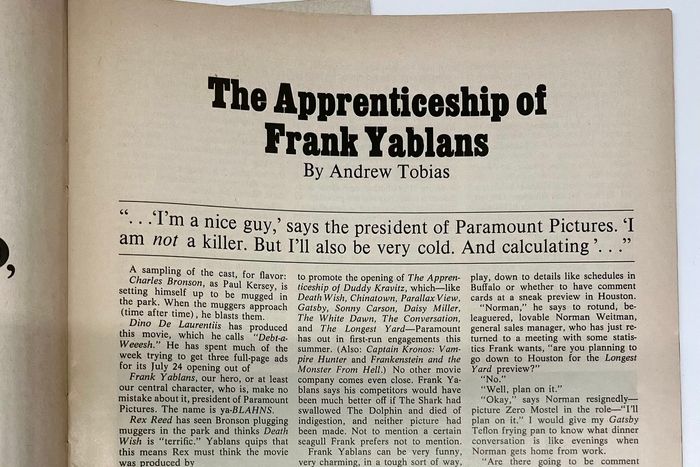

“We were eyeball-to-eyeball and I got the full force of his sales pitch. And he was killing me. He was telling me he knew how to sell, and he was selling me! I mean, I didn’t know what to do. And what I usually do at moments like this is I shuffle my feet — and I happened to look down and I realized I was six inches lower than he was. You know that split-level office he has — was so taken with the view, and with him, I didn’t notice it at first. So I got up on his level, so he had to look up, and he said, ‘Sometimes I’m not as tall as I appear.’ Everybody laughed, including Frank, and that sort of broke the spell.”

QUICK TAKE:

YABLANS: Does someone have the minutes of the last meeting where I said Norman Weitman’s estimates are full of s- – -?

NORMAN: That’s in the minutes of every meeting, Frank.

FADE IN: A day in mid-July. Last night Frank screened a film at home in Scarsdale, then stayed up until 2 a.m., he says, reading the Magicam status report. He has arrived at his office, via chauffeured limousine, at 7 a.m., finished a three-hour breakfast meeting with “the chairman,” and finds Dino De Laurentiis waiting for him on his way into the Magicam presentation. (After which there will be lunch at La Grenouille with David Merrick, an advertising/publicity meeting, a visit from his tailor, a business dinner, and, at home, another screening.)

“What the hell kind of shirt is that?” Frank demands playfully of one of his staff as he and Dino and I walk past into his office. “You look like the mayor of Puerto Rico.” With me around, Frank is being charming again.

Dino and Frank begin playfully arguing about the gross on Walking Tall, a picture similar to Death Wish. Dino says it’s grossed $40 million; Frank bets him $100 it is closer to $14 million, and produces a $100 bill. Dino unravels five 20s, which Frank deems marginally acceptable.

Buzz. “Barry, what’s the latest gross on Walking Tall?”

The answer comes back, $14.3 million. Frank jumps up and down with delight (but doesn’t bother to actually collect the $100).

Dino is still pushing for three full pages for Death Wish. Frank says, “Dino, have i ever f- – -ed you?”

“Som-a-time,” Dino says, like a hurt child.

“Never! Come on, Dino, never!”

“You-a try,” Dino offers, by way of compromise.

Frank holds firm at a full page Sunday, a half-page Wednesday (opening day), and then, if the reviews are good, a full-page review ad on Friday. (They stay up all night to put together these review ads.) Dino leaves, saying, “Frank fokk-a me every morning. Frank-a no work good unless he fokk-a me every morning.”

Click here to preview your posts with PRO themes ››

Dino De Laurentiis, Europe’s biggest producer come-to-America, has made or presented nearly 600 films over the years and is worth tens of billions of lire. He got started, he has recalled, collecting discarded bottles on Capri,

filling them with tap water, and labeling them something like “Capri’s Famous Water of Life.” He and Frank have an informal partnership which Frank describes this way: “There is no formula at all with Dino; it is project by project. I consider him under a moral obligation to come to me with everything he has, and I consider myself under a moral obligation to reject anything I don’t like.”

Will Death Wish inspire an actual vigilante to murder muggers? “Possibly,” says Frank. Is there anyone who censors films for this kind of problem?

“The responsibility is our own,” says Frank. Has a script ever been turned down for “social-responsibility” reasons? “No.”

And, while I am on the subject, a related one. I asked Charles Glenn, Frank’s top marketing man, what Paramount would do if, hypothetically, it had an absolutely dreadful film the executives were convinced no one — but no one — would enjoy, but to which they thought they could draw enough people; through a catchy title, ads, etc., to recoup their investment. “We would release it,” Glenn told me candidly.

This is a business, after all. The marketing department has been working up a list of areas where crime in the streets is highest, and will target special efforts on Death Wish there, hoping to stir up the kind of controversy that will get people to the box office.

CUT TO: Ted Zephro, who, as I’ve said, became Frank’s right-hand man in the sales organization. Ted is in an exhibitor’s office arguing about terms. (In this business, each deal is negotiated.) Ted has just kicked one of the office chairs through a partition to make his point. The exhibitor, cool as a canister, looks at Ted, raises his eyebrows and purses his lips, as if to appraise this performance, and says — “not quite, but almost as good as Frank.”

Frank came up this route, field sales, first with Warner, then Disney, then Filmways, and finally Paramount. He knows the size and feel and “house nut” (break-even) of every major theater in the country.

“Frank swore the day he arrived,” says Zephro, “that he would become president of the company — and I just laughed. ‘Play your cards right,’ and all that stuff, he told me, ‘and I’ll take care of you.’” Less than two years later, Charlie Bluhdorn, who had hired him to captain through disasters like Paint Your Wagon and Catch-22, made him president.

“We got our money back on those films,” Frank notes with satisfaction.

As Zephro recalls: “Frank didn’t allow anyone to see Catch-22. He was the only one who was gonna see it, right? So we’re waiting for him outside the screening room and he comes out, and I swear to God, if he doesn’t win an Academy Award, no one will. His eyes are glossy — I says, ‘Frank, how’s the picture?’ He says, touched me so much, I really can’t even talk to you right now.’ And he just walked off, like — like into the sunset. I think he wouldn’t let anybody else see it because he knew it was a stiff, see? This is how smart the f- – -ing guy is. He got me and some of his other top guys so f- – -ing high on this picture that when we went out in the field, we killed, you know. We thought it was the coming of Christ, this picture. He makes up a policy for distribution terms on this film that’s the roughest policy that was ever perpetrated on the exhibitors. He said he wanted to raise $12 million in front — never before done. I said, ‘Frank, I’m not going to get these terms.’ He says, ‘Zeph, I’m depending on you.’”

Anyway, says Zephro, “We did raise $8 million on the picture and made these deals. When I saw the picture I almost threw up. I told Frank and he says, ‘Shut. up, will ya — I know what I’m doing.’ I says, ‘What about the exhibitors?’ He says, ‘I know how to handle ‘em. We’re going to have another one coming down the line and they’re going to have to pay for that one, too. And they’ll stand in line for you.’ And he ended up right, because the next picture we had was Love Story, right? And Frank went through the same goddamn thing — only this time he let us see the picture.”

“One of the great problems in this business is collecting our film rentals,” Frank explains. “So we evolved a program here of getting our money in advance. On Catch-22 we got $12.5 million before the picture was released.

On Godfather we got $15 million or $16 million before the picture was even shot. They didn’t pay, they didn’t get the picture. It was that simple. On Great Gatsby we collected $18 million prior to release, and on Godfather Part II we will collect thirty … two … million … dollars,” he says with special emphasis, of which $5 million is already in — four months before release. “Now, that doesn’t mean that if Godfather II bombs we’re not going to have to give back some of that money, because it’s not in our interest to bankrupt a theater —”

CUT TO: Ben Sack, who owns all the big Boston theaters, telling me that he predicts 40 percent of all the exhibitors will be bankrupt within six months or a year. “Exhibitors are being made the suckers of the industry,” he says, “having to put up guarantees for movies that haven’t even been made yet,” and with new theaters costing three times what they used to to put up.

CUT BACK TO FRANK, SAYING: “— but what it does assure us is if we sell the picture to play 20 weeks, before that theater gets back any money it’s going to have to play it 20 weeks. And in those 20 weeks we’re going to earn quite close to whatever that money is, even if the film is a disappointment.” What’s more, explains Frank, “They’re not going to get Godfather II until everything else is paid up, too, so they really can’t defeat it. They may not be paying other companies,” he smiles, “but they’re paying Paramount.”

If, on average, Paramount is getting its nearly $300 million annual revenues 90 days faster than a less well-managed company would, then, with money going for one percent a month these days, Paramount’s pretax profits are

boosted $9 million by this policy.

The other Yablans innovation, beginning with Catch-22 and perfected with Gatsby, is in hyping every last ounce of potential out of a selected few super-films that are actually only mediocre. Love Story, for example, was, in Frank’s words, “a very light picture, a very small picture. And, of course, we made it a phenomenon.”

Just how is a little less clear. First of course, there was the book, though that certainly didn’t help with Jonathan Livingston Seagull (whose financial flight was presaged at Frank’s grand-premiere press conference when Jonathan relieved himself in Frank’s hand). Then there was the kind of sales hype Ted Zephro described. Further, Frank says, “We didn’t let anybody see the picture; we built up a kind of mystique. And we had that copy line — Love Means Never Having to Say You’re Sorry — which was an integral part of it, only because nobody knew what the hell it meant … Then, of course, there was the whole romance of Bob and Ali …” And there was also skillful attention to the right marketing and distribution details.

This does make a difference. On Chinatown, for example, Buffalo was out of line. “We moved the schedule ahead an hour,” Frank says, “and the grosses immediately shot way up. In Memphis we opened up to $6,800 the first week, we changed the ad, which was too sophisticated for Memphis, and we grossed $8,000 in the next three days.” Or this: Gatsby, like Godfather, opened in five New York theaters. “In retrospect,” says Frank, “perhaps we shouldn’t have opened in five theaters, because had we only opened up in one or two, there was enough pressure on Gatsby to have built enormous lines, and those enormous lines would have buried the critical reviews. Buried them. Because a person that reads Vince Canby and sees it’s a terrible review, but goes out and sees he can’t get into the theater, he’s got to figure somebody’s crazy — either the 5,000 people in the line or Vincent Canby. And so part of the marketing strategy is, you want those lines. They feed on themselves.” There is no question in Frank’s mind, he says, that opening Gatsby in a single theater would have added millions to the eventual gross of the picture.

_

BIG TAKE: In a unique (and hush-hush) incentive plan for movie company executives, both Evans and Yablans have been given, presumably with the blessing of Gulf+Western’s chairman, if not its shareholders, “points” in Chinatown — that is, a percentage of the film’s profit. If each man does indeed have 10 percent of the profits, as has been estimated, and if the picture eventually grosses $20 million–plus, as Frank expects (on a production budget of $3.3 million), then each man’s six-figure salary could be supplemented by a nice seven-figure bonus. Frank is pushing Chinatown.

_

BRAWL SCENE: Of course, there is more to job satisfaction than money alone. Even as this piece goes to press, the continuing saga of Paramount’s power politics and powerful egos seems to be heating up a bit. Frank reportedly wants to move his headquarters to the West Coast, which would put him where the glamour is, tighten his control over the studio operation, and, at the same time, loosen Charlie Bluhdorn’s hold on the company. Charlie, the word is, won’t let him go. Bob Evans, meanwhile, worries that from 3,000 miles away his true worth may not be fully appreciated by Bluhdorn (though sources report that it is). And Yablans has floated a trial balloon about going independent—not because he really would do it, but to remind the 42nd floor of his indispensability. It’s contract negotiation time.

One knowledgeable man in the industry, who has worked extensively with Frank, says that even considering the tyrannical movie men of old, “Frank has alienated more people in the industry than anybody else ever did.” Paul Newman, for one, has sworn he’ll never make a picture for Frank — but then Robert Redford swore the same thing and has just signed to do Six Days of the Condor (a co-production with Dino).

“Those [actors and directors] who are alienated,” Frank says, “I would have to say are immature and don’t realize that I have no personal animus towards them.” He pauses a minute to reflect. “There are several I have a personal animus to, because I think they’re unnice people. Really unnice people. I don’t think I’ve made more enemies than Cecil B. De Mille or Jack Warner or L. B. Mayer or Harry Cohn. Nor have I made any more friends than they made. I do what I do the way I do it. I’ve never said that I’m the most popular man. But by. the same token, I’m a lot more

decent than some of the popular men. A lot more decent. Because I’m basically in a rejection business, and I will give a fast no and a fast yes. It’s difficult not to alienate someone in a rejection.”

CUT TO: Stanley Jaffe, Frank’s predecessor. Stanley wants to make a movie from a screenplay called “Polo Lounge.” (In Los Angeles, everyone, including Frank, stays at the Beverly Hills Hotel. The bar is called “The Polo Lounge.”) Evans and Yablans both hate the script. Stanley, hysterical (all right, well, I’m telling this story the way movie people tell it) — Stanley, hysterical, goes to Frank and says, “If I got George C. Scott for the lead, would you do it?” Frank gives a fast yes. Stanley asks how much he can offer Scott, who’s been working for $1 million and up lately. Frank says, $100,000. Stanley, outraged but not licked, says he will make up the $900,000 difference himself, and, to everyone’s surprise, signs Scott for $1 million. Stanley comes back to Frank, just a trifle triumphant, and announces that he’s got George C. Scott. “Stanley, you’re f- – -ed,” says Frank candidly. “We’re not going to do the picture even with George C. Scott.”

CUT BACK TO FRANK SAYING — “So I’m aware of some of the problems I have,” Frank continues. “I’m trying to refine them — I don’t want to be an abrasive personality. But by the same token I’m not about to get off the lines of the mission that I see … I’m a nice guy. I am not, I am not a killer. I am not a killer. And I would much rather help somebody than hurt somebody. But I’ll also be very cold. And calculating.”

Frank’s intercom buzzes. “What?!” he demands. “I’ll call him later.”

“How do you handle Gatsby,” Frank continues, “and do the outrageous things we do and make the outrageous statements we’ve made, and get $18 million in advance, without getting a lot of other presidents’ noses out of joint? And I can’t help it if Redford feels that we turned Gatsby into a circus, and yes, I get upset when Redford says something about it because Redford is going to make a million-six or a million-eight by the fact that we made a circus out of it. Because if we are to believe the critics are accurate — that they would have hated the picture anyway, without all the promotion — then the picture would have done $3 million instead of $35 million.” (“I would like to have two critical failures a year like Gatsby,” Frank is fond of saying.)

Frank says most of the Yablans stories that make the rounds are untrue. “I mean, to have Paul Newman say he doesn’t like me because I’m a fascist — I mean, my God, you know, I’m a bleeding-heart liberal, not a fascist! Paul Newman and I met only once. So that’s the kind of business we’re in. We’re in a vicious business.” Even so, says Frank, he has made “a concerted effort to find out what it was I was doing wrong.” “Certain things,” he admits, “I was doing wrong. Certain calls should have been made … Maybe picking up the phone and calling somebody and saying, ‘Gee, I understand that you heard such-and-such and I just want you to know that’s not the way I feel. And it’s appreciated, you know. That kind of thing. But you can’t spend time doing it. You really can’t.”

Some of the ego-bruising he’s done, he says, “was really due to my own peculiar sense of humor, which is quite acerbic at times, you know.” For example, he says, he was asked to visit a columnist’s home. “And the person was very proud of her new home,” he recalls, “and she said to me, ‘Well, how do you like it?’ And I said, ‘Well, you know, to me it looks like early-Mediterranean Queens.’ Which I thought was very witty. And everybody laughed, and she laughed — but she was angry as hell! So I had to call up, and I said, ‘C’mon … how can you be upset at that?’”

One famous Paramount director describes Frank as, “incredibly ambitious, a total egomaniac, publicity crazy — he wants to be very powerful and very wealthy, and in the course of it steps on people if he has to. I suppose he’s okay if you know all that. But I don’t respond to that kind of man.”

But Peter Bogdanovich thinks Frank is “a terrific guy.” “I have no complaints about Frank,” he says. “I’ll tell you something that somebody said about him, an actor friend of mine. He said, “When you look into Frank’s eyes, there’s life there. And most of those business people tend to have rather stony, cold, dead eyes. Frank is full of impish fun and warmth.’”

Well, half-full, anyway.

P.S. Dino got his three full pages in The Times, as Charles Bronson — BLAM, BLAM, BLAM, BLAM — murdered three more junkies.

FLASHBACK

Frank was born on August 27, 1935, which made him 39 last month. (I had been told he lies about his age, but Boys High School confirms that he entered the ninth grade in 1949.) For this birthday this year, the New York office hired band and printed up “Yablans for President” buttons as the theme of the party. Presumably the party-givers were referring not to power struggles with Paramount, but to Frank’s oft-quoted desire to become president of the United States. (Frank agrees he hasn’t a hoot of a chance, but thinks it’s healthy to aspire to big things.)

“We led a very quiet, typical, old-fashioned neighborhood life,” says Frank, “a kind that really doesn’t exist anymore. It was a nice way to grow up. We didn’t have money, but money wasn’t all that important. We had chicken soup on Friday night, and lots of love and affection. We were also instilled with the belief that you could do whatever you wanted to do, you know. Not an age of cynicism.”

The family wasn’t religious at all, though Frank and his brother Irwin were bar mitzvahed and “had to go through the tortures of the rabbi with the bad breath and the steel ruler.” And in school — was he bookish? athletic? “No,” he says, “I was a lover. I was a lover. I was an actor [first role: a white-gloved killer] … I was a damned good actor. A damned good actor. But mostly I went steady. I think I started going steady when I was about 6. I’ve always liked to be with one girl at a time [he has been married to Ruth Edelstein of Milwaukee for 17 years now] — I needed that kind of relationship, I suppose.”

He was active in sports, he says, but not very good. “I was a rather frail, rather small child, and I still don’t really give a damn about sports. I play tennis and golf now, and I do rather well, because I cheat,” he grins.

Frank didn’t like being a teenager, “because when you’re a teenager you’re a punk — nobody listens to what you have to say.” And no, he “never gave a damn about film.” He’s not a film buff now, he says, even though he will screen six or seven pictures on a typical weekend. His favorite film? “I think that almost all the movies are my favorite movies,” he says, though when pressed, the first film that comes to mind is Cabaret. —A.T.