There’s a scene early on in John Woo’s Bullet in the Head (1990) that remains one of the most extraordinary things I’ve ever seen in a movie. Tony Leung and Fennie Yuen are having a teary-eyed breakup; he’s tangled with some gangsters and must flee Hong Kong for Vietnam, and even though they’re engaged she doesn’t think she can wait for him. As they talk, a massive riot rages behind them; Molotov cocktails fly all over the place as police and protesters attack each other. (It’s the late 1960s in Hong Kong, a politically turbulent time.) The two lovers’ farewell is intercut with a policeman in heavy protective gear attempting to defuse a bomb. They share one last passionate kiss, then say their final good-byes as the bomb goes off some distance behind them. And as Leung and Yuen walk away in different directions, Woo cuts to pieces of the now-dead bomb-defusing expert falling to the ground, all in elegant slow motion. It’s absurd. It’s grotesque. It’s sublime. It never fails to make me cry and laugh at the same time. Bullet in the Head is a film so deranged it makes The Deer Hunter look like Diary of a Country Priest, and I love the whole thing, but this particular moment is one I still think about on a regular basis.

Newly restored, Bullet in the Head is one of 21 Hong Kong classics that are in the midst of a momentous Stateside rerelease from Shout! Studios. (Six of them are currently screening at IFC Center, and another five will start this Friday, August 22. Digital and physical-media releases are also in progress; a five-film Jet Li collection debuted on 4K and Blu-ray last month, with more to follow.) These are all part of the Golden Princess film library, a 156-title catalogue of movies made from 1979 to 1995 that represent some of the most important works of the golden age of Hong Kong action cinema. The best known of these are probably Woo’s The Killer (1989) and Hard Boiled (1992), the two action masterpieces that established the director’s reputation in the U.S. and led him to Hollywood, where he made hits like Face/Off (1997) and Mission: Impossible 2 (2000). Also screening at IFC are Ringo Lam’s boozily delirious 1987 undercover-cop thriller City on Fire, whose climax Quentin Tarantino famously lifted for the infamous Mexican-standoff finale of Reservoir Dogs (1992), and the Better Tomorrow series, the first of which, produced by Tsui Hark and directed by Woo in 1986, marked Woo’s first collaboration with iconic star Chow Yun-fat.

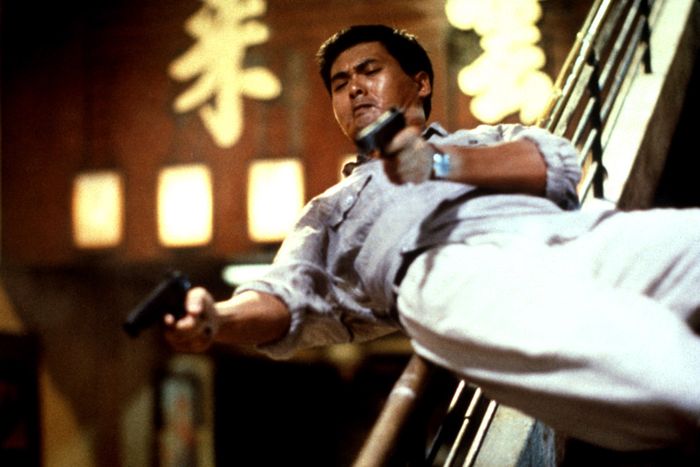

A scene from John Woo’s Bullet in the Head (1990). Photo: Tai Seng/Everett Collection

These films demonstrated an almost experimental approach to action, with creative camerawork, unorthodox editing, and unabashedly over-the-top emotions. Woo’s work was shot through with a deep romanticism; Tsui’s pictures had sinewy, dancerly rhythms; Ching Siu-tung, who made the immensely popular A Chinese Ghost Story and the Swordsman series (Swordsman II, released in 1992, probably remains the pinnacle of the wuxia genre), delivered acrobatic explosions of phantasmagoria. The levels of craft and technique in these movies were high, and so too was the violence. Combined with the sincerity onscreen, this style of filmmaking was the opposite of anything coming from Hollywood, with its stoic action stars and ironic approach to both narrative and emotion. Chow Yun-fat was the epitome of cool (as were Jet Li and Tony Leung and Anita Mui, not to mention Michelle Yeoh), but his characters were not withholding or unreadable; they were open-hearted. What makes Hard Boiled and The Killer so incredibly powerful aren’t just the actors’ badass poses and Woo’s slow-motion delivery of balletic gunplay and pyrotechnic mayhem, it’s the fact that the protagonists are so unabashedly heartfelt in all their tortured longings and loyalties.

“I’m a romantic guy,” Woo says today, speaking to me from Los Angeles. “It’s in everything I do, no matter what.” He says that a lot of his work during this period was driven by a quest for beauty and emotion. That sounds painfully simple, but it led him in visionary directions. A deft editor, he always sought new ways to convey his characters’ outsize emotions. He recalls that this is how the bomb-defusing scene from Bullet in the Head came about: “They’re in love and they’re separating, but when I’m cutting, I want to send the message that they will be destroyed by this war.”

Woo also credits his artistic success to the freedom he was given by the producers and financiers he worked with. “When we chose an idea, sometimes we sent the studio a script, sometimes an outline, sometimes just a few words. They’d ask, ‘Who’s in it?’ I’d say, ‘Chow Yun-fat.’ ‘Okay, how much?’ ‘About $30 million.’ ‘When do we have a script?’ ‘I don’t know. Maybe a couple of months.’ ‘Okay, here’s the money, go make the movie.’” This allowed him to be both creative and impulsive. For example, the spectacular (and immortal) opening tea-house shootout in Hard Boiled was filmed before there was any kind of script or story, because Woo had found out the building was about to be torn down and wanted to preserve its memory on celluloid.

Indeed, with Golden Princess, directors and producers often enjoyed an unprecedented degree of latitude, especially by Hong Kong standards. “One of the reasons so many people worked with them was because they always said, ‘We don’t need to make all the money,’” says Grady Hendrix, co-author of These Fists Break Bricks: How Kung Fu Movies Swept America and Changed the World, and one of the founders of Subway Cinema, which launched the New York Asian Film Festival in 2002. “It used to be that if you wanted your movie exhibited in a Hong Kong theater chain, they would charge you for the electricity they spent to light the marquee with your title on it. They would charge you every time they played your trailer. And the Golden Princess guys were like, ‘We don’t have to do that. We’re going to take a straight 5 percent of the box office, full stop. We don’t have to screw you.’ And when John Woo almost wrecked Golden Princess financially with Bullet in the Head, because it was so expensive and no one showed up to see it, they said, ‘John, this is your best movie. Who cares? It’s just money. We’ll make more later.’”

Chow Yun-fat in John Woo’s Hard Boiled (1992). Photo: Rim/Everett Collection

After Golden Princess ceased filmmaking operations in the mid-1990s, however, the rights for these movies wound up with the Kowloon Development Company, a real-estate corporation in Hong Kong, which is also one reason why they’ve been so hard to see for so long. (Golden Princess itself had started life as a real-estate venture, owning and operating cinemas, and had begun making films in the early 1980s as a way of generating product to put on their screens in the highly competitive Hong Kong marketplace.) “Their business was real estate, and they simply didn’t have the bandwidth to make licensing a full-time job,” says Jordan Fields, who heads acquisition efforts for Shout! and who negotiated the deal for the rights to the film library for an undisclosed sum.

That all changed a couple of years ago when producer Weldon Fung decided it was time to find a home for the entire collection. Weldon had grown up in the Hong Kong film industry and witnessed this period of resurgence in the 1980s and early 1990s; his late father, Gordon, was one of the founders of Golden Princess. When Gordon fell ill a couple of years ago, Weldon approached the owners of the library and offered to find a company to take over the entire collection. “People would keep asking for individual movies, like A Better Tomorrow or The Killer,” Fung says. “So I just started to tell them, ‘If you want that classic movie, you have to buy the whole library.’”

Click here to preview your posts with PRO themes ››

The negatives, Fields says, will still remain at the Hong Kong Film Archive. “They’ve lived there forever, and they won’t leave there,” he says. “What we do is check out two negatives at a time, take them to a post house in Hong Kong, scan them, and return them to the archive. Then we take those files and do all the restoration and color grading and other work here in the U.S.” This also accounts for why the movies will be gradually rereleased in batches, with more to come in subsequent months and years as they’re restored.

Rewatching these films today, in all their restored glory, I can’t help but get nostalgic twinges about this period. It was an intoxicating time to be a young cinephile. While kung-fu films and other genre movies from Hong Kong had for decades fed the grind-house circuit and the growing network of Chinatown cinemas in North America catering to the diaspora community, the work of directors like Woo, Tsui, Ringo Lam, Sammo Hung, Siu-tung, and others broke through among audiences, especially young film buffs, in dramatic fashion during the late ’80s and early ’90s.

“It was so hard to find things that were different and to see something with that level of craft and artistry,” says filmmaker and teacher Paul Francis, who was one of my Hong Kong moviegoing pals back in the day. “They were using Hollywood language and Hollywood techniques, but it was such a different sensibility. The extremity of what you’re seeing onscreen matches the emotional journey of the characters. So even if it’s fantastical and unbelievable, it makes emotional sense because that’s how the characters are feeling.”

Peking Opera Blues (1986). Photo: Gordon’s Films

I myself first discovered Hong Kong cinema thanks to a couple of NYU film students, Graham Winick and S. Craig Zahler. One night they sat me down and made me watch a Japanese laser disc of Tsui’s Peking Opera Blues (1986), a delirious period adventure-comedy-romance that’s alternately yearning, goofy, and reflective. I was enraptured by the vivid colors, by Tsui’s visual wit and rapid-fire editing. The janky subtitles flew by so fast that I only caught about 30 percent of the plot, but no matter; I was hooked. Winick and Zahler informed me that the same director had also made a movie called Once Upon a Time in China that I just had so see; they made me promise I’d go watch it the first chance I got.

In New York, you could go see something like Hard Boiled at Cinema Village, then make your way to see Once Upon a Time in China at Film Forum on Houston Street, then stroll further down to the cinemas in Chinatown — the Sun Sing on East Broadway, directly under the Manhattan Bridge; the Rosemary on Canal Street, which is now a Buddhist temple; and the Music Palace, on Bowery — to discover the really new stuff. (Many of the pictures that made it up to Cinema Village and Film Forum would screen in Chinatown months earlier.) Those latter theaters didn’t list their showtimes in the mainstream press, so usually you had to walk in and see if you liked what they were showing. “It was an amazing experience,” Winick recalls. “They’d show these double features, and we’d go every weekend, without necessarily knowing what was playing. We’d smuggle in steamed pork buns. There would never be heating, so in the winter you had to bring two coats. Occasionally cats would climb the screen.”

If you wanted videos, you could peruse the colorful shelves of Chinatown media stores, which stocked Japanese laser discs (and later VCDs) of Hong Kong movies, or head over to Kim’s Video, which offered a generous selection of questionably sourced videotapes for sale. For the truly adventurous, there was the 43rd Chamber near Times Square, a small, converted newsstand that sold cheap VHS dubs of the latest Hong Kong films that had hit laser disc in Asia; they even had a small VCR/TV combo by the counter where you could double-check the quality of the copy and whether the subtitles were readable. (I later found out that folks like Tarantino, RZA, Wesley Snipes, and Samuel L. Jackson also frequented this store.)

Zahler eventually became a filmmaker himself, making intense, acclaimed genre movies like Bone Tomahawk (2015) and Dragged Across Concrete (2019). Though his efforts are quite violent in their own right, Zahler admits that they are nothing like the Hong Kong masters he adores to this day. “When I was in film school, I liked to see the mechanics of the filmmaking up on the screen,” he says. “There are a lot of wide-angle shots in Tsui Hark and John Woo’s films, so you’re feeling the lens, whether you’re cognizant of it or not. And then with Woo, with the slow-motion and the beautiful approach to the choreography, he’s really calling attention to the aesthetics of the filmmaking, but the movies are also really emotional.” That perhaps gets at the heart of why these works found such purchase in the hearts of young cinephiles. The pictures’ earnestness is matched by the clear joy evident in the filmmaking. The movies draw attention to themselves but without any irony.

The Chinatown theaters, of course, died out a long time ago, as did Kim’s Video and the 43rd Chamber and the bootleg-VHS shops and the dubious mail-order catalogues that helped nourish many a developing film nerd. Criterion did release The Killer and Hard Boiled on laser disc back in the 1990s, but the market for a lot of these pictures dried out aside from occasional one-off theatrical screenings for the most popular titles. (Criterion also put out a beautiful box set of Tsui’s Once Upon a Time in China series a few years ago, as well as recent 4Ks of Johnnie To’s The Heroic Trio and Executioners, so the company continues to do solid work keeping Hong Kong classics alive.) The news that Shout! was acquiring the entire Golden Princess library feels like a watershed moment, both for those who will discover these movies for the first time and for those of us who discovered them decades ago.

Woo himself seems to be the happiest of all. These recent revival screenings began with a premiere of the new restoration of Hard Boiled in Los Angeles earlier this month, with the filmmaker himself in attendance. Though he’s a living legend now, he’s also still clearly touched whenever his work finds its audience. “They all stood up and applauded!” he says. “After so many years, they are still so excited about this movie. I wanted to cry when I walked onstage.”