The Oscar-, Emmy-, and Tony-winning costume designer Paul Tazewell has mastered the practice of developing memorable sartorial articulations of freedom and the pursuit thereof. It’s a feat most recently recognized in his work on Jon M. Chu’s Wicked (and its sequel, Wicked: For Good), but the 61-year-old designer has been thoughtfully transforming characters through clothing for more than half his life.

With his Broadway debut in 1996, Tazewell designed costumes for Bring in ’da Noise, Bring in ’da Funk, which united its tap-dancing characters across class with kinetic vibrancy. There were contemporary hip-hop silhouettes — baggy jeans and shorts, rendered in the yellow, green, black, and red palette of ’90s brand Cross Colours — alongside military garb and the preferred uniform of the upwardly mobile, the suit. But all were selected, cut, and tailored to emphasize stomping, statement-making, free movement.

Tazewell has prolific theater credits, including Hamilton (2016), Memphis (2010), The Color Purple (2006), Ain’t Too Proud (2019), and Suffs (2024). The fact that Tazewell, at age 16, began his costuming career designing for his Akron, Ohio, high school’s production of The Wiz is part of his professional legend at this point. Now 61, Tazewell has spent much of his life in the headspace of the greater Wizard of Oz universe. He won an Oscar earlier this year for his costume-design work on Wicked, making him the first Black man in the history of the award to win and the second Black person overall (Ruth E. Carter, who won for Black Panther, was the first). With turns as costume designer for The Wiz Live!, Harriet, Jesus Christ Superstar, and West Side Story, Tazewell has demonstrated a facility for thinking across eras and worlds with liberation being the leitmotif of his work.

Tazewell holds a philosophical, unshakeable, familial occupation with freedom. Though he grew up in Akron, he had deep connections to Bennett College, a renowned women’s HBCU in Greensboro, North Carolina, where his great-aunt Willa Beatrice Player served as president from 1955 to ’66 and where his mother and sisters were educated. Player stood in firm support of the Greensboro Four, a group of students from neighboring North Carolina A&T who orchestrated and participated in sit-ins to desegregate public spaces, particularly the Woolworth’s lunch counter. His grandfather was also a member of Akron’s Urban League chapter.

“I carry with me all of the support and knowledge and insight into the mark that Black Americans have made on this country,” Tazewell tells The Cut from his home in Brooklyn. “I’m very privileged to be in a position to take up space in this way. My search is always to figure out: How am I making my mark? How am I being additive to the Black story? How can I stand as an inspiration for other people that look like me and beyond? This is my way of carrying the torch, having come from the people that raised my parents, and then my parents raising me and my brothers. All of it is connected and it informs how I prioritize the projects that I work on, and then what that point of view is when I’m telling that story.”

Liberation is a theme in your work, from Hamilton to Harriet to The Wiz and Wicked. Is there an aesthetic of freedom, and if so, what is it?

It is viscerally felt for me, and it has different faces. The vision of freedom for Harriet is different than it is for Wicked, although those primary characters are played by the same person. Cynthia Erivo and I developed a relationship through Harriet, and then we were able to maximize that into Wicked, partially because it was breaking reality. Some of that early work on Harriet was the intimacy of getting to know each other, establishing our trust in each other, establishing a language of how we see clothing and how we can communicate with depth.

Cynthia honors what I do in the same way and with as much reverence as I acknowledge what she does as a performer. It works together when I’m trying to figure out: What does it mean to be a liberated woman in the 19th century? What was that for a Black woman to be able to do everything that Harriet Tubman did? How remarkable is that? She was also a shape-shifter and a very smart woman. She grew up as a little girl trapping animals, which made her understand the waterways she had to traverse so that she could then guide her Underground Railroad passengers to safety. That’s the beautiful thing about being in the position of telling that story as a costume designer, because I have to then research that to understand who the character is.

With that in mind, tell me about Elphaba’s coat in Wicked: For Good. It’s got these wide lapels, it’s extremely textured, nipping in at the waist and then this voluminous bottom.

The beginning thought of that costume was to establish her silhouette as nostalgic of the 1939 Wicked Witch of the West. It’s an 1890s silhouette that has been used for that character we know and love from The Wizard of Oz, played by Margaret Hamilton. You’ve got the pointed hat with a wide brim, the dress, a cinched waist, a full skirt, and then a cape. But that’s been upcycled by Elphaba. We’ve seen it originally in the first film when Fiyero and Elphaba take the cub to the forest, and we see that it’s a raincoat hanging over the bicycle. I wanted to establish that she already has this as part of her wardrobe, so that we understand that she’s collected all of her things and moved into exile into the treehouse, her home. And in that treehouse, she has the ability to re-create her life. She has a loom and she has ways of knitting and sewing. She’s creating furniture for herself, and she’s creating a life and a space of wellness and safety for herself.

The coat is part of a badass look for a heroic character. I also wanted for the coat to still retain those elements of texture — that it’s like tree bark, that it aligns her with the organic, which is similar to the mushrooms that are the texture of her dress. She actually still wears that dress underneath as part of her uniform or her superhero look; it’s just in tatters. If she were to take off the coat, you would see that there’s a tunic that’s pretty much shredded away except for at thigh level. And then she has trousers, knee-high badass boots, and a broader brimmed hat, which is very similar to the original Wicked Witch of the West.

Did you split the design work for each individual film?

I designed Elphaba’s whole rack of clothing for both films. We didn’t know that we were going to be shooting two different films. We didn’t know that it was going to be broken up until we were well into production. I needed to figure out what the whole costume story was going to be. I needed to know, Where is Elphaba going to go and how am I going to represent her as she evolves in this character?

The way you work with black made me think of Kerry James Marshall and how this one color can be rendered so differently across paint formulations, brands, and pigments. You do something similar with black fabric, creating various textures. Even with all that black, Elphaba never disappears into a shadow.

I love the medium of fabric and what that brings to a design, the difference that it makes, and then also fabrication techniques, whether it’s pleating or creating interesting applications for a specific fabric. Silk chiffon versus a silk organza versus a silk satin … they each have sculptural specificities that allow them to operate in certain ways. In our preproduction period, we did screen tests. This was an opportunity to really investigate with Alice Brooks, our cinematographer, and with Jon M. Chu, our director, what shows up well onscreen. How can Alice best light the costumes that I’m designing, if it’s going to be the different colors of pink and how we see the different colors of pink that I’m choosing, or if it’s Elphaba, how to capture the depth and detail of her costumes?

Click here to preview your posts with PRO themes ››

From left: From top:

It was a priority for me that they both are balanced in interest and in beauty. I didn’t want Galinda the fairy princess to overshadow Elphaba, who’s wearing all black all the time and is not sparkly. In some cases, I’m putting a color and a texture underneath a solid black so that it will just provide more depth. That coat is like an oil skin, so it’s a waxed linen, and that has a sheen that stands out against the silk chiffon, which is her tunic. And then the leather of her boots and all those different elements are all black, but they’re all a different texture. Then she’s got the black velvet cape, and that’s been mottled and distressed.

Let’s talk about Galinda’s bubble dress and the transformation that she undergoes. It hints at a mermaid color motif.

It was trying to capture the idea of the iridescence of a bubble when it’s moving through space, and just how the color shifts and changes that kind of rainbow effect that a soap bubble has. This is the first time that we see her in this lavender-pink. There’s a pink quality in there as well as a soft blue. It was acknowledging the original Wicked Galinda dress, the bubble dress from the musical. It was also, silhouette wise, acknowledging the Billie Burke Glinda dress from The Wizard of Oz, the 1939 film. So all of those elements together are creating this vision, which is, it’s her first bubble dress when she’s gifted the bubble machine from the Wizard.

From left: From top:

You see her march across her terrace, she wields her wand as a baton and steps up and is fully empowered. The pink bubble dress is the one that we are presented with at the very beginning of the first film and then through the interior of For Good. She’s in a blue-and-lavender dress. But if you look at the imagery that we have on the skirt, especially, it’s that same kind of swirl pattern. It starts as a two-dimensional application, and then it’s carried into the bodice. That same kind of swirling energy is what you see when we graduate to the pink bubble dress, which is the Fibonacci spiral cones that create this kind of abstract sculptural skirt shape. It’s the Galinda of the 21st century.

Like everyone in this universe, the Wizard’s clothes are beautifully tailored. He makes this life that he’s selling, this life of ease and feeling good, so alluring. It’s incredible and very powerful that he’s not rendered in a way that’s more literal, like with a Brioni suit and a big red necktie. It allows you to see why people would be drawn to him and what he’s selling, even if it’s ultimately snake oil.

He’s the greatest showman. He’s Barnum and Bailey. He has coerced a whole land to follow him. There’s a black dressing gown. It has an emerald-green lapel. There’s a border that’s been embroidered, it’s poppies, running down the front and then around the hem. That’s an Easter egg of the culture of the Wizard of Oz, because remember the poppy field? Dorothy falls asleep and they’re trying to wake her up. If you remember, Elphaba’s mother was dressed in red. I’ve dressed Mrs. Thropp in a red velvet dress. It had a silk organza and gauze skirt that is in the shape of a poppy that’s turned upside down. It’s to give you this idea of this woman who has been affected by using a drug, which is how Elphaba ended up turning green. It’s connecting all the dots so that we’re making a story, an unspoken story, out of the clothing.

The Wizard of Oz has become iconic within queer culture. Dorothy’s blue gingham dress hangs in the window of the Stonewall Inn. If you could pick a costume to hang there, in conversation with that dress, what would it be?

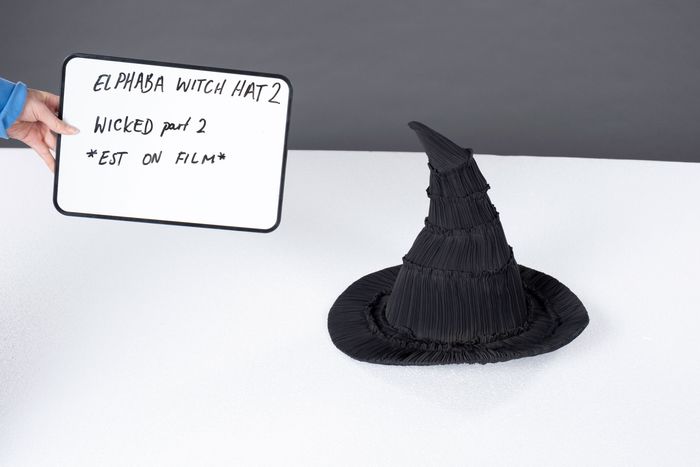

My choice would be the Wicked Witch look for Elphaba in the For Good film. And if I had to choose a single element, it would be the hat, because I think that that is indicative of everything that I was hoping that the character would embody. It relates to nature. It is reflective and nostalgic of a silhouette that we recognize, but it is made into its own thing with how it spirals. Cynthia was able to wear it with great swagger, and I think that that is part of it as well.

Do you feel you’ve done everything you can do in the Ozian universe?

No. Oh my God, I don’t know. I mean, offer me a story. I think that my work is a reaction to the text that describes a place. I bring visual life to what is written or what’s spoken. If someone else wanted to tell the story in a different way, then I would find another entryway.

Tell me about working with Thom Browne and Janelle Monáe to create that delightful look for the “Superfine” Met Gala this year. It was so energetic and playful.

Thom Browne and I were in the room with Janelle figuring out how to best support how she wants to present herself. It was maximizing his sensibility as a tailor. For me, it was the push toward a vision that could expand into costumes but not bridge too far away from fashion. That event is tricky because it’s always on the fence of extreme. There’s never enough time. I was really quite pleased with how everything turned out.

The first time that I dressed Janelle was for Harriet. So, another full-circle moment. She’s an amazing woman. She is a powerhouse, and her sensibility is always on point. She always wants to make a mark. She wants to be seen. She is the queen of Halloween as well. With that kind of sensibility, she is one of the only people that I could imagine wearing that look in the way that she did.

How has winning an Oscar changed your relationship to your work?

I talk about my work so much more, which is beautiful. I love being able to engage in a broader way, whether it is about costumes or it’s about other kinds of design, which I see as the next chapter. It’s opening a door to more opportunity, more points of view on design beyond costume design. I mean, I’ve been designing costumes for 35 years. It’s been a significant amount of time that the world of costumes has been in my life, and it’s been the language that I speak. I want to make use of this opportunity to consider design, whether it is luxury items or specialty fashion or interiors. It’s all intentional. It’s all informed by how we want to feel when we’re in a space, and what elements will help us to feel a specific way. How can I make a mark that says something about my personality?

Every day when I’m working with different characters, it’s not a costume that’s going to hang on a hanger. It has to come to life on a person’s body, and it is informed by how they’re playing the role. I’m in that kind of creative space. I just want to focus it in a different direction that will be inclusive of lifestyle.

Would 16-year-old Paul have any notion that you would be in this creative playground today?

I was always creating, always making a mess. Writers have to write, painters have to paint. There’s a part of me that has to create in this way, engage in this way. It’s a part of me, and I accept that, and that is a beautiful thing, and I want to do justice to that. If space continues to be provided, opportunity continues to be provided, then I will use my gift to continue to tell stories through costumes.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.