Michael B. Jordan glided into the wine library at his hotel seemingly unaware that, for a man who plays a vampire in his latest movie, the ambience he’d chosen was a little on the nose. It was a Monday afternoon in May, and outside, midtown Manhattan was a sunny 73 degrees, but our windowless meeting room shielded us from the light. As I scanned the bottles of red liquid lining the walls, a server shuffled in to ask Jordan if he would like something to drink. “You guys got a lemon-ginger tea?” he asked.

Jordan had just arrived from London, where he was in preproduction for a reboot of the romance caper The Thomas Crown Affair, a project he’s been developing — first as a star and producer and now as the director at Amazon MGM Studios — for more than a decade. He’d also just wrapped up the promotional tour for Sinners, the hit $341 million–grossing vampire thriller that sparked countless think pieces about race, appropriation, and cunnilingus; the kind of culturally dominant movie discourse that hasn’t been seen swirling around an original film since Jordan Peele’s Get Out introduced “the Sunken Place” into the lexicon eight years ago.

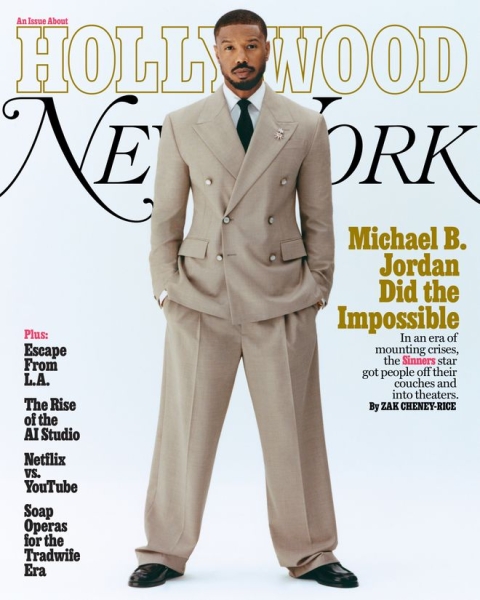

The Hollywood Issue

The Great Realignment

- It Feels Like 2009 on Dropout

- Even Netflix Is Jealous of YouTube

See All

When we met, Jordan looked and moved like an athlete at a postgame press conference, wearing a boxy T-shirt and roomy pants, neither of which could hide the bulk of his shoulders, the swell of his biceps, or the self-possession of his posture. The press tour for Sinners has taken him around the world; when I asked him which places he most likes to visit, he rattled off a comically nonspecific list: “Going to Mexico City, first, is always a great experience. They love movies. Atlanta is always a lot of fun as well. Brazil is another place.” He was courteous but reserved — he told me that sharing as little of himself as possible “creates a demand.”

Even though his partnership with Sinners director Ryan Coogler has been wildly profitable for both of them — a smash indie debut (Fruitvale Station), followed by a blistering run of critically acclaimed blockbusters, from Creed to Black Panther and its sequel, Wakanda Forever — the initial Hollywood reaction to Sinners’s success was chilly. Industry reporters and studio executives seemed oddly keen to undermine the movie’s box-office performance. The New York Times downplayed its $46 million in opening-weekend North American ticket sales as having “a big asterisk.” Variety stressed in a viral X post that “profitability is still a ways away,” citing the movie’s high production and marketing costs. One executive warned Vulture that the unusual production agreement between Warner Bros. and Coogler, in which Coogler obtains ownership rights after 25 years, “could be the end of the studio system.”

Across the industry, risk aversion and austerity rule the day. Theatrical attendance still hasn’t recovered from its pandemic-era collapse, and domestic film production appears to be in a death spiral, which makes the fact that Sinners performed so well all the more remarkable. To Ben Fritz, who covers the industry for The Wall Street Journal, “there is this almost resentment and frustration in a lot of Hollywood … Like, ‘How did these guys get to make an original movie for $100 million?’”

All of which contributed to a broader sense that Jordan’s marquee status has been underestimated. In recent years, Glen Powell, the Tom Cruise–mentored star of Hit Man and Twisters, has been characterized as having been born “25 years” too late, so seamlessly could he have fit alongside movie stars of yore like Harrison Ford and Arnold Schwarzenegger. Timothée Chalamet has parlayed his Oscar nominations and his blockbuster performance in the Dune franchise into perennial Gen-Z “It”boy status. And Paul Mescal has managed to become a target of heartthrob-hunting paparazzi while being taken seriously as a thespian — even as the middling Gladiator II left his movie-star bona fides in question. Jordan is rarely mentioned in the same “future of the industry” conversations. “We should ask why Powell is the actor who’s going to save movie theaters instead of Michael B. Jordan, who has starred in numerous blockbusters but doesn’t seem to get any good opportunities outside of franchise films,” wrote film critic Noah Gittell in 2024. Matt Belloni, a Hollywood columnist for Puck, told me “Sinners does a lot” for Jordan being taken seriously as a “real” movie star because, previously, “he’s never been in anything [successful] that is not IP-related.”

Coogler described Jordan’s value-add bluntly. “I’ve been blessed to make movies for a massive global audience, you know what I’m saying?” he told me. “Mike qualifies as my friend now. But don’t get it twisted. What I need is something that’s very rare. I need movie stars.” Deadline reported that an exit poll conducted on the opening weekend of Sinners set out to break down why people went to see the film on the big screen. The pollsters came back with Jordan’s name as the No. 1 reason, according to almost 47 percent of respondents.

He certainly looks the part. At 38 years old, Jordan is young, Black, charismatic, vaguely political but not divisively militant — an ideal assuager for the terminally image-conscious film industry’s post–George Floyd anxieties. When we talked, he was only marginally aware of any Sinners backlash: “I didn’t read the articles or know who wrote them.” Between promoting Sinners and prepping for Thomas Crown, Jordan confessed, “I haven’t really been out in the world.” But he knew the movie had ardent defenders, like Ben Stiller, who’d blasted Variety’s coverage on social media. Soon, Tom Cruise would declare himself “a huge fan” and name Jordan his heir apparent.

Now, the question is whether Jordan can continue to deliver on the hype on his own, without Coogler, at a time when Hollywood’s yearslong on-again, off-again love affair with Black A-listers is very much in flux. His directorial debut, Creed III, did well at the box office — a franchise best of $276 million globally — with critics commending it as a promising first Rocky movie without Rocky. He’s got several upcoming projects: I Am Legend 2 and an adaptation of Tom Clancy’s special-ops thriller Rainbow Six, along with speculative plans to make a fourth Creed movie. Like the older leading men whose careers he wishes to emulate — “Denzel, Tom Cruise, Will Smith, Leo” — he doesn’t just want to be a star but a mogul with a diversified portfolio. As Vulture critic Alison Willmore wrote last year, that requires seizing the means of production. “Having a production company used to be a means of flexing your star power,” she wrote, “but increasingly it looks key to cementing that power in the first place.” Jordan has a production company, Outlier Society, which doubles as a laboratory for developing his own projects, plus thriving side careers as a brand ambassador, philanthropist, and sea-moss-beverage entrepreneur, among other pursuits. “I like playing chess,” he told me in a way that made playing chess sound less recreational than mandatory. “Long game.”

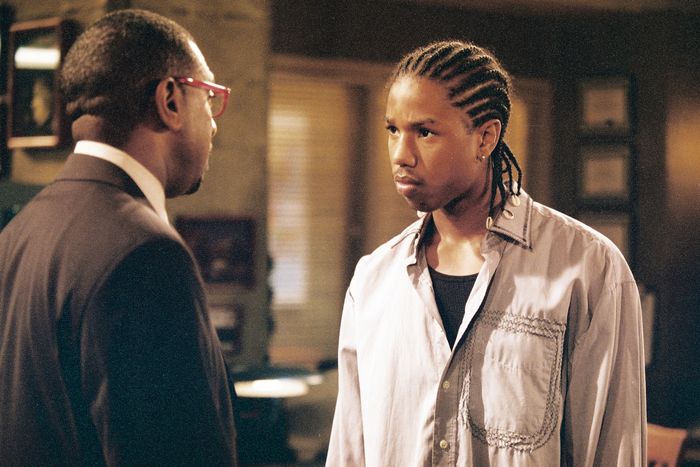

ROLE CALL | 2001: Jamal in Hardball. 2002: Wallace in The Wire. 2004: Reggie Montgomery in All My Children. 2009: Vince Howard in Friday Night Lights.… more ROLE CALL | 2001: Jamal in Hardball. 2002: Wallace in The Wire. 2004: Reggie Montgomery in All My Children. 2009: Vince Howard in Friday Night Lights. Photo: United Archives GmbH (Hardball); Alamy Stock Photo (The Wire); Virginia Sherwood/Disney General Entertainment Content (All My Children); Bill Records/NBC (Friday Night Lights).

The plot of Sinners hinges on a Faustian bargain. Jordan’s characters, twin brothers Smoke and Stack, return home to the Mississippi Delta in 1932 to open a juke joint with money they made working for Al Capone in Chicago. On opening night, as the mostly Black patrons enjoy a hallucinatory, blues-fueled revelry, a group of white vampires arrives at their door asking to be let inside. They offer as payment not only money but “fellowship” — a psychological escape from Jim Crow. But the hidden terms of the offer soon come into focus: The leader of the vampires, a white ghoul named Remmick (Jack O’Connell), wants to use the power of the blues to commune with his ancestors, which he can accomplish only by subsuming the Black musicians and entrepreneurs into his undead horde, stripping them of their humanity and severing them from their culture. A bloody siege ensues; Stack gets turned into a vampire, forcing Smoke to choose between his life and eternal communion with his brother.

Jordan gives a commanding dual performance. He leans into his smoldering physical presence as Smoke, the older and more taciturn of the two, a character on whom the world, and the trauma he’s experienced in it, weighs heavily. Jordan described Smoke to me as the “still” one who “doesn’t move around too much … whose pain was right here. He had a hole in his chest. He was the old man. He was tired of keeping up with Stack,” his loquacious younger brother. Stack showcases Jordan’s charm and restless energy. “I wore tight shoes” to encourage him to keep Stack in motion, Jordan said. “I wanted them to walk different; I wanted their body language to be different.”

Destin Daniel Cretton, who directed Jordan in 2019’s Just Mercy, likened Jordan’s work ethic to that of a competitive athlete. “It was like somebody taking shots, and every take would get him more energized to do the next, and do it better and better and better.” You can see that discipline in his best roles. In Creed, he plays Donnie, the orphaned son of a famous prizefighter who grew up cycling through juvenile detention and feeds his resentment on the underground boxing circuit. While training with Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky Balboa to fight the reigning light-heavyweight champion, Donnie begins a romance with a singer who’s losing her hearing — each subplot emphasizing how this fundamentally tender and kindhearted person is fighting only to compensate for his childhood deprivation. A similar dynamic drives Jordan’s Black Panther villain, Erik Killmonger, who wants to rule the African utopia of Wakanda so he can arm oppressed Black people with its state-of-the-art weaponry. Killmonger’s deeper motivation is sadder and less grandiose: His father, the brother of the late king, was murdered by Wakandan agents, forcing Killmonger to grow up alone and exiled from his ancestral homeland.

Jordan’s overall physicality is especially well suited to playing these sympathetic characters who get knocked down, get up, and hit back. There’s a softness to his features that, for fans of his early TV work, calls to mind his huggable tough-kid roles on The Wire and Friday Night Lights — while also inspiring, for example, readers of People magazine’s 2020 “Sexiest Man Alive” issue to whisper to themselves, “I can fix him.” I asked a friend before I met Jordan if she was a fan. “You mean, ‘Do I want to have sex with him?’” she helpfully corrected me.

2012: Maurice Wilson in Red Tails. 2012: Steve Montgomery in Chronicle. 2013: Oscar in Fruitvale Station. 2014: Mikey in That Awkward Moment. Photo: L… more 2012: Maurice Wilson in Red Tails. 2012: Steve Montgomery in Chronicle. 2013: Oscar in Fruitvale Station. 2014: Mikey in That Awkward Moment. Photo: Lucasfilm Ltd (Red Tails); Collection Christophel (Chronicle); Alamy Stock (Fruitvale Station, That Awkward Moment).

The worst-kept secret about Jordan’s success is that it’s as much about his strategy and discipline as about his natural gifts. His mind-set at the time of his star-making turn in Creed was not yet so strict — the film was a strategic coup, but he still seemed to lack a measure of poise, at least offscreen and outside the gym. Two months before the movie came out, in September 2015, Jordan was profiled by GQ. The first few sections of the article describe a dinner at an upscale Lower East Side restaurant, during which Jordan, then 28, sticks a wad of chewing gum under the table as revenge for being made to wait too long at the host station. He proceeds to drink too many tequila-and-cucumber cocktails — “I’m drunk, for sure,” he admits — then, during a visit to his childhood neighborhood in Newark, New Jersey, describes his youth in such deprived terms that his mother was later compelled to clarify them. He shares fond recollections of his days as a Fast and the Furious–style street-racing hobbyist — behavior that, were he a young white actor of an earlier era, might’ve been romanticized as mere “wild child” exploits.

But while it was all pretty tame, as displays of celebrity immaturity went, Jordan seemed to feel he’d been caught slipping. “I think there’s a hard lesson to learn,” he told me. “And I learned it.”

The lesson was also about whom to trust and being more careful in conversation. While arranging a Vanity Fair profile in 2018, he expressed concern about being profiled by a white reporter. “There is an unspoken language between people of color,” he told the magazine. “When you deal with journalists and writers who are trying to observe from the outside, and what they think you’re trying to say, it doesn’t always connect.”

Yet there’s a calculated guardedness when Jordan does press that defies any reporter’s racial background. The same goes for what he shares on social media. “Why would they pay to see you on a weekend if they see you all week for free?” Denzel Washington once advised him about the perils of overexposure. Dating rumors have become like ambient noise for Jordan — any woman photographed in his vicinity is liable to prompt speculation — but the only partner he’s confirmed is the model and socialite Lori Harvey, whom he dated from 2020 to 2022. “There was no real thought behind” that decision, he told me. “At that moment, I was like, Ah, fuck it, whatever.” But that sense of abandon is unusual — Jordan considers himself to be a “thoughtful person and a well-intended person,” which means both knowing when to talk and, perhaps more important, when not to.

If a sensitive topic arose in our conversation, the change in Jordan’s demeanor was noticeable — longer pauses and murkier answers. He declined to answer my question about Sean “Diddy” Combs, who is currently facing sex-trafficking, racketeering, and prostitution charges. Casandra “Cassie” Ventura, Combs’s ex-girlfriend and a key witness in his trial, claimed to have had a “flirtation relationship” with Jordan in 2015 that allegedly led to Combs threatening the actor over the phone. As a result, Jordan’s name was brought up during jury selection not long before we met, along with at least 189 other people’s. (Jordan has not publicly addressed his relationship with Ventura.)

He’s been open about his willingness to work again with Jonathan Majors, who was convicted of misdemeanor assault and harassment for an altercation with his then-girlfriend that occurred after he filmed Creed III. More stories have since come out about Majors being cruel and belligerent on other sets, which Majors has denied. I asked Jordan how he might convince a skeptical crew member that Majors was safe to work with. “To be brutally honest, I haven’t even thought about it yet, man,” he said, mainly because they don’t yet have a project in production. “The energy to thoughtfully break that down — yeah, I can’t give that right now.”

The subtext to any discussion of Majors’s legal troubles is that he was formerly enjoying one of the most meteoric trajectories in all of Hollywood. A gifted actor seen as having franchise-headlining potential, his celebrated indie role in 2019’s The Last Black Man in San Francisco led to an HBO series, Lovecraft Country, before Marvel handed him the proverbial keys to the car by casting him in Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania as Kang, the villain around whom the studio’s next phase of productions was supposed to revolve. Majors soon joined the ranks of promising Black male A-listers whose careers have either stalled or imploded. The death of Chadwick Boseman belongs in a separate category — a seismic tragedy for both Jordan, who worked closely with him on Black Panther, and the industry, which lost a formidable talent with cultural cachet and a proven box-office track record. But Anthony Mackie, John Boyega, and John David Washington have all experienced either straight-up commercial failure or career stagnation, while LaKeith Stanfield has starred in two of the best American movies of the past decade — Sorry to Bother You and Judas and the Black Messiah — neither of which set the box office on fire. Daniel Kaluuya is perhaps the only Black leading man who rivals Jordan’s mix of critical acclaim and box-office success. But as one of the few reliably bankable Black A-list actors, Jordan has a responsibility that he’s gone to costly lengths not to squander.

Seven years ago, Jordan hired a videographer to document his life. “The intent was me feeling like I don’t take in the moments,” he explained. “Because I’m always on the go, always working and grinding. One day I wanted to have something to reflect on outside of the memories in my head.” The filming is less frequent nowadays — Jordan promoted the original videographer to director’s assistant on Creed III, then to associate producer on Thomas Crown — nor was it ever meant to be narrated or contextualized using reality-TV-style confessionals. The documentarian’s job was to hit RECORD and watch with the goal of creating a “family archive” that might, for instance, explain to Jordan’s nieces and nephews “why Uncle Mike is always gone” or show to his “great-grandkids when I’m dead” to “understand a bit of where they come from.” And while Jordan says the public will likely never see the footage, it’s evident that it captures a man who dedicated his life to becoming a star by forsaking much of the time and perspective required to enjoy it.

This conundrum is part of what motivated Jordan’s since-abandoned plan to work as hard as possible before turning 30, then quit Hollywood altogether. “I’ve missed out on a lot of life,” he told me. “I’m not complaining — but that balance is something I’ve always struggled with, of the personal and professional stuff.”

2015: Human Torch in Fantastic Four. 2015: Adonis Creed in Creed. 2018: Erik Killmonger in Black Panther. 2019: Bryan Stevenson in Just Mercy. Photo: … more 2015: Human Torch in Fantastic Four. 2015: Adonis Creed in Creed. 2018: Erik Killmonger in Black Panther. 2019: Bryan Stevenson in Just Mercy. Photo: Alamy Stock Photo (Fantastic Four, Creed); Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures (Black Panther); Warner Bros (Just Mercy).

Warner Bros. was in an especially shaky position when it got ahold of Coogler’s script for Sinners back in 2024. At the height of the pandemic, the studio had dumped Christopher Nolan’s movie, Tenet, on HBO Max on the same day as its theatrical release, against his heated objections. Nolan was furious; he took his next project to Universal, effectively bidding “good riddance” to the studio that had released all of his movies since 2002’s Insomnia. That next project turned out to be Oppenheimer, his Oscar-winning opus. The debacle went down as an era-defining humiliation for Warner Bros., once considered the most artist-friendly outfit in town.

After the box-office disappointments of last year’s Joker: Folie à Deux and March’s Mickey 17, Bloomberg reported in March Warner Bros. Discovery CEO David Zaslav was interviewing for co-CEOs and chairs Pamela Abdy’s and Michael De Luca’s replacements. (A Warner Bros. Discovery spokesperson denied this: “The rumor of an imminent leadership change at the studio is not accurate.”) Abdy and De Luca desperately needed a win with Sinners’s Easter-weekend release approaching. But they were confident in their investment in Coogler, whom they considered a once-in-a-generation talent — and who, at just 39 years old, is now the most critically and commercially successful director across his first five features since Steven Spielberg.

“Sinners was probably the least risky thing we’re going to do this year,” De Luca told me. And Jordan was critical to its success. Five years ago, it would’ve been impossible to avoid the squishy language of “diversity” when talking about Warner Bros. Discovery’s investment in him — how it was a “win” for Black representation that showed the studio’s commitment to “amplifying Black voices” or some such. The change in emphasis reflects a broader shift in popular culture. Today, Abdy emphasizes the broadness of Jordan’s appeal: “Men like him; women like him.” The post–Oscars So White energy that propelled Moonlight to a Best Picture Academy Award, Jordan Peele to bankable auteur status, and Zendaya to being, reportedly, one of the highest-paid Black actresses in TV history has ebbed in concert with the drifting enthusiasm of “affluent white liberals,” the social milieu “from which the people who run studios come,” explained Fritz, the Wall Street Journal reporter. And with the Trump administration taking a blunderbuss to anything that remotely resembles DEI, the mood across the entertainment industries is generally apprehensive.

“Sometimes things are the most loud in the beginning of anything, as far as media coverage, conversations,” Jordan told me when I asked if he felt the momentum behind Black-led projects from roughly 2016 to 2020 had stalled. “A wave has come, and we should ride that one. And when that one passes, then the next wave … I’m optimistic. I have to be. You know?”

2025: Stack and Smoke in Sinners. Photo: Warner Bros.

There’s little disagreement among those who cover Hollywood that Jordan is due for an Oscar nomination. “Wasn’t he nominated for Fruitvale?” asked an incredulous Belloni, the Puck columnist. (He was not.) In its granular breakdown of which elements of Sinners most merited Oscar attention, Vanity Fair singled out Jordan’s performance as “arguably his finest work.” Variety, just one week after weathering the blowback from its coverage of Sinners’s box-office performance, wrote that “Jordan, overlooked shamefully for Fruitvale Station and Black Panther, now demands Oscar attention.”

It’s hard not to measure this buzz against how ambivalently Jordan thought about his acting prospects 12 years ago — before he met Coogler. “I was really, really, really unsure of what my career was going to be,” he told me. “Am I a TV actor? Where am I going? And I was like, Man, I just want an independent film. I can show what I can do, and I just need to know if I could carry a film or not, if I could be a lead.” Not long after that, his agent sent him the script for Fruitvale Station, which he read in tears during a flight from South Africa back to Los Angeles, where he met Coogler a few days later. “He told me he thought I was a movie star,” Jordan said. “He thought I was a great actor, and he wanted to show the rest of the world that, and he wanted to make the movie with me.”

Now his team treats that status as a given. “Mike deserves to be a leading man, period,” said Phillip Sun, Jordan’s agent turned manager. “He happens to be a Black leading man. But we weren’t chasing roles just based on color. We chased everything.”

His becoming a director has only helped, in part by placing him several steps ahead of whatever pitfalls might lurk on a given set. “I think the bigger thing with me on the set this time around was I was able to give Ryan another set of eyes,” he said of acting in Sinners, his first movie as an actor since his directorial debut. “I know he’s coming into a close-up for certain things, so let me go over to makeup real quick and make sure I get the blood already touched up on my hands so by the time he comes in, I’m already ready to go. I ain’t got to wait for something to tell me that’s what we doing next.”

It’s apt that he would choose this moment in his career to play Thomas Crown. The Machiavellian billionaire art thief, previously portrayed by Steve McQueen and Pierce Brosnan, is as detached and inscrutable a character as they come — a businessman with a million crises spiraling around him who nevertheless keeps his cool. The meticulous equanimity with which Jordan weathers his own personal conflicts, including the mounting obligations of being No. 1 on most call sheets, comes from years of experience. “I wasn’t old enough to play that dude” when the opportunity first arose some 13 years ago, he said. Now, “I’m at the right time.”

Production Credits

- Photograph by Philip-Daniel Ducasse

- Styling by Jason Bolden

- Grooming by Tasha Reiko Brown

- Hair by Jove Edmond

- Suit by Louis Vuitton Men’s

- Brooch by David Yurman

Thank you for subscribing and supporting our journalism. If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the June 2, 2025, issue of New York Magazine.

Want more stories like this one? Subscribe now to support our journalism and get unlimited access to our coverage. If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the June 2, 2025, issue of New York Magazine.

Click here to preview your posts with PRO themes ››