Virgil Abloh taking a bow after his debut for Louis Vuitton Men’s in Paris on June 21, 2018.

In January 2018, Louis Vuitton announced that Kim Jones was leaving his post as its menswear designer. During his seven-year tenure, Louis Vuitton blossomed as an emblem of luxury, art, and streetwear. Jones gave owner Bernard Arnault and his company LVMH even more to boast about. The wild success of a 2017 Supreme collaboration received special notice in that year’s annual report. That venture reportedly reaped €100 million in revenue. But it hadn’t just been a commercial success. It connected Louis Vuitton to something more elusive than money: the mood of the moment. In 2011, LVMH revenue was just under €9 billion. When Jones departed, it was well over €18 billion. As one might expect, Arnault didn’t let Jones go far. The designer moved over to Dior Homme, and shortly thereafter the fashion industry began to speculate on who might fill his shoes at Louis Vuitton.

Virgil Abloh was then five years into running his own fashion label, Off-White. Born September 30, 1980, in Rockford, Illinois, to Ghanaian parents, Eunice and Nee, he broke into the popular consciousness in a way that other Black designers before him did not. He engaged in an endless list of creative pursuits. He designed stage sets and album covers for his friend and collaborator Kanye West (now known as Ye), water bottles for Evian, furniture for Ikea, cars for Mercedes-Benz, and, most important, sneakers for Nike. He had recast the industry’s idea of a designer, shifting it from the image of a tortured creative soul striving to perfect his craft, or a lifestyle guru telling customers how to dress, eat, and shelter, into a kind of cultural impresario — someone who spotted rising trends, who excited a community, who sold a feeling of belonging with a simple logo, and who made the purchase of a varsity jacket feel like a sociopolitical gesture on par with integrating a lunch counter. His Off-White was a repository for a new way of thinking about how luxury and Blackness converged. Abloh would sometimes say that Off-White wasn’t his brand — although it very much was— but rather our brand. Such positioning was his self-written permission slip to absorb whatever might have been in the air and inject it into a collection. We’re all in this together.

Abloh had demonstrated his talent on terms set by the white Establishment; he also helped to transform the terms by which future talent may well be judged. He came to fashion as an outsider, but he checked many — although not all — the boxes deemed necessary for success in the industry. He did this as he loudly professed his disdain for boxes. To further his ambition, Abloh had hired a public-relations team to help him launch Off-White in 2013: Karla Otto. Established in 1982, Karla Otto, named for its German-born founder, was part of fashion’s old guard. The international firm worked with designers Jean Paul Gaultier and Jil Sander and had even worked with West on his first runway show in Paris. Karla Otto personally did her part to set West up for success. She assembled key fashion editors in an environment in which they could focus solely on the clothing and not West’s fame. She stood by his side backstage as he fielded questions from editors. When he began to flail, she didn’t halt the interviews or otherwise intervene. That was how fashion worked — even for a celebrity.

In selecting Otto’s agency, Abloh also took a note from Sean “Diddy” Combs, who launched his Sean John collection in 1998 with the assistance of Paul Wilmot Communications, another of the industry’s legacy agencies. Even before the unveiling on the main floor of the Bloomingdale’s flagship in New York, the PR firm had advised Combs on how to engage with the fashion industry, on what he needed to do to be invited inside instead of having to break down the door. And following that advice, Combs dutifully attended other designers’ shows. He wooed editors. He took their questions. So Abloh did, too. “Who are the people I need to know?” he asked his publicist, Kevin McIntosh. “Let me meet them so I can see how the game is played.” Abloh was especially eager for an introduction to Vogue’s longtime editor-in-chief Anna Wintour (today Condé Nast’s global chief content officer).

Social media was Abloh’s way of circumventing traditional fashion media. But he loved Vogue and wanted the magazine to take note of his accomplishments. “I used to obsess, when I was young, looking at those magazines and being like, ‘This is design. I want that fancy photo in front of, like, a dog, with maps and all that.’”

Wintour declined, on multiple occasions, to attend an Off-White show. Her reticence was not particularly unusual. Wintour didn’t make a habit of going to runway shows of upstart designers — not unless they were being nurtured by Vogue. And becoming one of Vogue’s babies was, well, a matter of talent, lineage, commercial clout, likability, and the favor of the gods.

Like so many young designers before him, Abloh ferried his collection to the Vogue offices to allow its editors to assess his line. As much as folks complained about Wintour’s more than 30-year tenure as editor of Vogue, as much as they dismissed the magazine as past its prime, a meeting with Wintour remained one of fashion’s stations of the cross, a valuable one.

Vogue took real notice of Abloh in 2015, and he was introduced to its readers in the September issue with an article that had him interviewed by phone from various airports as he circled the globe working. The report focused mostly on his multitasking, on his hopping around the world to DJ, assist West, and, yes, work on Off-White. “The first show of his that I seem to recall attending was fall 2017, which featured so many leaves on the runway it looked like Central Park in November,” Wintour said.

About one thing Abloh remained clear: He wanted a big job at one of fashion’s big houses. He believed they needed what he could offer: a luxury language understood by young consumers. He’d mused about his chances of being hired at Givenchy when Riccardo Tisci departed in 2017. That was just wishful thinking and dreaming. The role went to Clare Waight Keller, who became the first woman to lead the house. But Abloh was making an impression among fashion executives.

In March of that same year, Abloh had a clandestine meeting with Donatella Versace to discuss his possibly designing Versus, the brand’s youthful diffusion line. Versace looked approvingly and longingly at Abloh’s relationships within the music industry, his devoted cadre of fans, and his ability to connect with people across borders — both racial and geographic. Versace wanted to be cool. Or at least cooler.

“Virgil was a true gentleman. He was incredibly kind and courteous when we met, and I loved his energy,” Versace said. Like so many others, she was charmed by him and marveled at his capacity to do so much. Abloh was intrigued by her overtures and presented a brief on his vision for Versus but ultimately decided Versus wasn’t the right fit for him. He backed away before an offer was on the table. Another suitor was more attractive.

In short order after Kim Jones’s departure from Louis Vuitton, fashion’s rumor mill began to speculate about Abloh succeeding him. Abloh seemed like a long shot for such a massive job, but Jones lobbied for his friend to be his replacement. On his Instagram, the departing designer posted a photograph of a pair of Off-White x Nike Air Jordan 1 sneakers that Abloh personalized for him. “Thanks Virgil,” Jones wrote. “Big love.” In addition to Jones, Abloh had other supporters within the luxury conglomerate. When Arnault’s son Alexandre became co-chief executive of Rimowa in 2016, he cast about in search of collaborations that could thrust the 120-year-old German luggage-maker into the public consciousness. Specifically, he wanted to grab the attention of millennials, who were driving 85 percent of luxury growth. The younger Arnault had brokered relationships with the Los Angeles–based streetwear brands AntiSocialSocialClub and Supreme. He turned his attention to Off-White and in 2017 promoted a Rimowa collaboration with Abloh’s label on social media.

Abloh also had in his corner Vuitton CEO Michael Burke, who had facilitated Abloh’s unorthodox internship at Fendi in 2009 and remained a fan. Burke had Abloh in mind to succeed Jones. “We spent time thinking about that and talking about what that would mean and where he would take Vuitton,” Burke said. “Where would he want to go with it? And what were my needs and what were my constraints?”

Louis Vuitton was the right European brand for Abloh. Maybe it was the only one that could have accommodated him. It was one of fashion’s oldest brands and had held the imagination of the hip-hop community for decades. It signified a particular kind of success: financial. It was equated with cash that was so freshly earned it was still wet from the printing. The LV logo announced one’s ability to buy extremely expensive products that even the most fashion obtuse would recognize. Louis Vuitton didn’t measure one’s level of sophistication; it highlighted one’s bank account.

As the world’s largest luxury brand, Louis Vuitton was a force of influence. It was sturdy. It already was a rip-roaring success; it wasn’t a brand trying to right itself. Menswear accounted for only 5 to 15 percent of its sales; it was a relatively low-risk division but one with plenty of room to grow. The company could bear up under the stress of an unconventional talent. It didn’t have a history as a couture house. Sure, it had company DNA, but it wasn’t mythical. It didn’t have the quiet social currency of Hermès, the glamorous hedonistic history of Gucci, the romance of Givenchy, or the idealized haute couture legacies of Dior and Chanel. Louis Vuitton products weren’t enshrined in a fashion system with the kind of reverence reserved for Dior’s New Look, Chanel’s bouclé jackets, or Yves Saint Laurent’s Le Smoking. Louis Vuitton made suitcases and handbags, the most familiar of which was probably the Speedy, which did not have the name recognition or aspirational patina of an Hermès Birkin or a Kelly bag. Its designers were talented men, but they were not larger than life. Each one brought a different sensibility to the house. Each had tugged the brand a little bit farther from its French roots, which were never that deeply planted.

“Vuitton had a kind of maturity to it so that it could really embrace disruption in a big way. The foundation was strong enough — as a leather-goods company — that they could bring amazing people on and let them loose,” said James Greenfield, the former director of Givenchy’s men’s division.

Soon enough, Abloh was sketching his vision for Louis Vuitton menswear. He quietly sent off sample garments from his collection so executives at Louis Vuitton could see real-world examples of his point of view and the quality of his Italian manufacturing. Finally, it was time for Abloh to meet with Bernard Arnault. It seems that every designer has an apocryphal story about the way they were vetted for an LVMH job. Ozwald Boateng recalled being taken onto the balcony outside longtime LVMH executive Yves Carcelle’s immense office to discuss Givenchy. John Galliano told the story of a James Bond–like armored limousine picking him up and ferrying him to LVMH headquarters. But a single tradition stands. A possible new hire of any magnitude met with Arnault over a lunch prepared by his chef and served in his private dining room in his Paris office at 30 Avenue Montaigne.

Arnault was a tall, slender man with gray hair, a high forehead, and a slow, considered manner of speech whether in English or French. He has been described as patrician, but he was not especially charismatic. Any hint of outsize charm may have been due to the fact that he was one of the richest men in the world, and depending on the state of the stock market, he had sometimes been the richest. When he moved through a fashion crowd gathered for one of his brand’s shows, he was surrounded by security as he headed to his seat of honor in the front row. He looked a bit like a human shark patrolling the waters, so there was a tendency for people to both stare and recoil.

As a young man, Arnault studied civil engineering at one of France’s most prestigious universities, École Polytechnique, and graduated in 1971. He went on to work as an engineer at Ferret-Savinel, his family’s construction company. He entered the fashion industry in 1984 by purchasing the bankrupt Boussac textile business. He was drawn to it because of a single jewel tucked amid the debris: Dior. The brand would later hold a distinct position within the LVMH fashion and leather-goods group — and in the heart of Arnault. “Dior is the most magic name in fashion in the world,” Arnault once said. But Louis Vuitton was always — and continued to be — the most lucrative one.

On the surface, Arnault and Abloh could not have been more different. Separated by more than a generation, Arnault played classical piano while Abloh was an aficionado of hip-hop and electronic dance music. Arnault, a white billionaire with vigilant security, had the ear of presidents both at home and abroad. Abloh, a Black entrepreneur with a penchant for connecting with anyone who popped up in his social-media feed, had rappers, streetwear designers, and neighborhood do-gooders among his contacts.

Yet they shared a background in engineering, which required both precise and creative thinking. They each understood fashion as a commercial pursuit while also presenting themselves as deeply connected to art. The two men sat down for lunch, along with Burke and Arnault’s daughter Delphine, a statuesque woman with her father’s high forehead and a face framed by shoulder-length blond hair. Delphine worked alongside Burke at Louis Vuitton; she also sat on the board of LVMH and shepherded the LVMH Prize for which Abloh had been a finalist.

The luncheon with Bernard Arnault was something between a test and a formality. By the time a job applicant was invited to break bread with the billionaire, a relationship of some sort was practically assured. “It’s very rare by that time that something would not go forward, but it can happen,” Burke said. Lunch began with Abloh explaining his vision for Louis Vuitton. In true form, once he began to talk, his opening sentence led into another sentence, which turned into a paragraph, which built into a monologue.

Click here to preview your posts with PRO themes ››

“At that time, everybody had the word street on their minds. It’s all about street, street, street, street, street, street. And so he basically explained what street meant to him,” Burke said. As Abloh talked, he scribbled on a sheet of paper. He started in the upper-left corner and kept writing and drawing as he spoke. Arnault mostly listened. Occasionally, the titan posed a question about the role of accessories in relation to ready-to-wear. He asked how shoes fit into Abloh’s vision of Louis Vuitton.

They talked about architecture too because fashion was retail and luxury retail remained very much a robust brick-and-mortar business. They discussed the things crucial to the success of a business that often go unmentioned — the human factors. Was he ready to take on something so enormous? And as Abloh answered Arnault’s questions, he continued to scribble. By the end of the luncheon, Abloh had written his entire game plan for Louis Vuitton on a single sheet of paper, not simply ideas about collaborations or products but the essence of what the collection would be: Who is the Vuitton man as done by Virgil? The piece of paper was a road map, a preview of what was to come. Abloh slid the paper across the table and over to Arnault, and the two men shook hands.

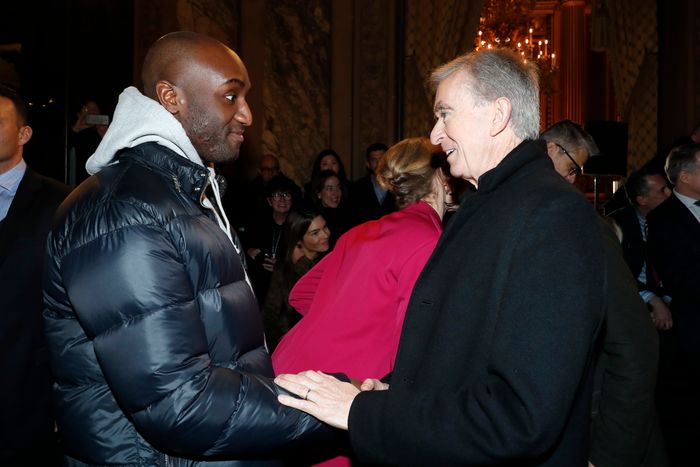

Abloh and Bernard Arnault

On March 26, 2018, Louis Vuitton announced Abloh’s appointment as artistic director for the menswear division. In his remarks, Burke noted that Abloh’s creativity and unorthodox background made him not only part of the fashion conversation but part of the pop-cultural dialogue as well.

The industry had drastically changed from the days when Paris was the center of creativity and style was defined by strict codes of attire such as cocktail dresses, house dresses, dinner dresses, luncheon suits, and business suits. Business casual upended established corporate dress codes. Urban centers such as Tokyo, Beijing, New York, and Los Angeles captured the imagination of designers, leading them to turn away from Europe for inspiration and to look more globally. Celebrities replaced the models. Influencers were the new social swans. Everyone was a jet-setter, even if they were flying economy. And fashion was slowly knocking down the walls separating streetwear from everything else. All those changes made room for Abloh.

He was elated with his new position; he was also overwhelmed and humbled. “The interview process was like eight months. And you could imagine my close friends having to hear me crying, screaming, moaning, being like, ‘What if they don’t hire me because of this? What if? What if they had an interview with somebody else and they were like, Man, you can’t do that?’ ” he recalled. “That’s what I was having to fight through — that it might not happen. That magic epiphany of what you thought was impossible, is possible, is better than any fashion collection or any shoe that I’ve released, period.”

It was what he’d worked toward in his professional life. The 17-year-old kid who’d saved up to buy a $75 Louis Vuitton key pouch, one of the least expensive items the company produced in the early 1990s, was now in a position to dictate the next obsession of a teenager living in the stillness of the American Midwest or the cacophony of Beijing. His first presentation was in four months. And because it was Louis Vuitton, it would be an event the entire fashion industry would be watching. Abloh had to work quickly, but he had the resources of a billion-dollar brand to create an extravaganza that would leave struggling independent designers in awe. It was also a test.

Not everyone was convinced Abloh was the man for the job. His design experience was essentially limited to a label that was persistently described as streetwear no matter how ill-fitting the term had increasingly become. “They want to call me a streetwear guy,” he said, referring to fashion editors and retailers. “I’m cutting a pattern and they’re still looking at the graphic on it or they don’t want to buy it if it doesn’t have words on it or something like that.”

Abloh moved into the Louis Vuitton headquarters on Rue du Pont Neuf, into a building with a classically elegant stone exterior and an interior that evoked the glass-and-chrome sterility of the modern business tower. His office retained the signatures of his predecessors, none of which he rushed to change. A Marc Jacobs–era bag from his collaboration with Richard Prince hung from a hook. The floor was ablaze in red carpeting celebrating the Louis Vuitton partnership with Supreme that Jones had orchestrated. Miles Davis played in the background.

Abloh’s most immediate decorating touch was to install turntables and several speakers the size of washing machines in front of windows overlooking the busy street below, from which he broadcast a show on Apple Music called Televised Radio. He maintained a steady stream of social-media posts, updating his fans on the status of his debut.

The 25-member design team that awaited him concentrated on realizing Abloh’s vision, which had begun, even at Louis Vuitton, with a T-shirt. But in this case, Abloh was focused on the details of it, not just a logo or graphic. “What’s the perfect weight? Why are fashion T-shirts usually so tiny?” he said. “I just want to find the size medium that a lot of people could wear and to not be oversized.”

Ultimately, the most distinctive item from that first collection was one that began with an early question to the design team: Why did the leather-goods house make clothes at all since that was not part of its history? One might well ask a similar question of brands such as Gucci, Prada, or Hermès, whose histories are in shoes and bags and saddles. But it’s hard to dress a model from only the feet down or to tell a cohesive story about style without the help of a few frocks. Abloh decided to focus on fusing accessories and garments into hybrid apparel, something he dubbed “accessomorphosis.” It was an Abloh-esque way of describing tactical gear, fisherman vests, and utility belts. Jackets came with built-in bags; coats had cutouts to accommodate fanny packs — or, in fashion’s new parlance, belt bags.

Accessomorphosis birthed the harness. The aesthetic flourish slipped over the top half of the torso. It merged suspenders with a shoulder holster. The newly minted creative director teased the design on Instagram and then wore a bedazzled custom version to the May 2018 Met Gala — the celebrity traffic jam that functions as a fundraiser for the museum’s Costume Institute. Abloh’s harness had been hand-beaded by the Louis Vuitton men’s atelier in shades of bronze and ivory to resemble an ecclesiastical raiment in celebration of the spring exhibition “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination.”

As the June runway show drew closer, a stream of messengers delivered what seemed like an entire greenhouse of floral arrangements, fashion’s preferred method of communicating good wishes. Assorted influencers — representing millions of fashion followers — wandered through the studios. Model Naomi Campbell bounded through wearing sneakers and leggings and was trailed by an entourage.

Every fashion show setting is a balance between logistics and personal aesthetics. For Abloh’s debut on June 21, 2018, he chose a location in the center of Paris. His runway wound through the courtyard of the Palais-Royal in the city’s First Arrondissement. The 17th-century complex took its name from its history as a former palace, but now its gardens were open to the public and its arcade was filled with posh boutiques. He selected a rainbow-colored runway and loosely based the show on The Wizard of Oz.

In the moments of anticipation before the show, when the rainbow runway was still immaculate and one could appreciate its borders of lush green trees, when there was a promising glow over the idyllic gardens, Abloh walked the runway alongside his mother, Eunice. He was looking down at his phone. She was looking off into the distance. The lower level of Eunice and Nee’s home in Rockford had become an ode to their son’s accomplishments. It was filled with photographs from his shows, one of the area rugs he designed in collaboration with Ikea, pictures of ebullient neighborhood kids after receiving Off-White sneakers from the designer himself.

Now, some thousand seated guests were invited to see his first show for Louis Vuitton, along with his family, including his wife, Shannon. The audience was filled with famous faces, those who had helped Abloh along the way as well as those for whom fashion was a lucrative source of self-promotion and for whom Abloh’s world was the latest advertising platform. The lineup included Kanye West and his then-wife Kim Kardashian West, as well as Rihanna and A$AP Rocky and assorted pop stars and influencers who represented millions of curious fans on social media. But the most important members of the audience might well have been the hundreds of Parisian fashion-school students who were there. Standing behind the rows of seated guests, the students wore T-shirts to match the colorful runway and formed a human rainbow. The words “Not Home” were emblazoned across their shirts in a reference to Dorothy Gale.

For fashion insiders, Abloh’s debut was the show of the season. It didn’t matter if it was a rousing success or an abject disaster; either way, guests had witnessed fashion history. Still, there was an awful lot of goodwill in the audience, which was not always the case. There had been more Schadenfreude than anything else in the air that night in Paris when West showed his first collection. But here, Abloh’s awe-shucks midwestern charm served him well. “In 32 years of modeling,” said Naomi Campbell, “I’d never felt that feeling of unified love from every single person there.”

West and Kanye West embrace after the designer’s Vuitton debut in 2018.

The 56-look collection was called Color Theory. The models were an impressively diverse group that included musicians Kid Cudi, Playboi Carti, Dev Hynes, and Theophilus London. They wore clothes that showcased Abloh’s desire for a size medium that really reflected a median body type rather than a lithe Hedi Slimane schoolboy. The show opened simply, with a dark-skinned Black man in loose-fitting, but not oversize, white trousers, a white shirt, and a matching double-breasted blazer. His sneakers were white, and so was the bag he carried, from which a white chain dangled. The contrast between the model’s dark skin and the white attire was beautiful and served as an aesthetic reminder of the glory of differences. The collection began where menswear once was rooted, in tailored silhouettes, but it moved quickly to where menswear now thrived with pullovers, T-shirts, and nicely cut hoodies. On Abloh’s runway, the traditions of menswear hadn’t been abolished. They coexisted with the more informal present. It wasn’t an either/or proposition.

In many respects, the clothes were simple and familiar. They did not upend the fashion orthodoxy. But Abloh’s distinctive voice was present in the poppy graphics, the abstract prints, the generously sized T-shirts, and the many vests and harnesses and utility bags. Many of the garments had an ephemeral quality because they were so light and translucent. That added to the optimistic mood of the show. The bold colors spoke of joy and youthfulness.

For those who found his work derivative, Abloh defended it as postmodern. If some found it lacked design finesse, that was okay because Abloh avoided calling himself a designer. When it seemed unsophisticated, well, that was because it was meant to speak to the 17-year-old mind-set. Overpriced? Value is about desire, not labor and material. To support him was to celebrate disruption and open-mindedness. To criticize him was to defend the status quo, to be a snob. Abloh declined to call himself a designer, so what exactly was he? Wildly creative? Or an incredibly creative bullshitter?

For many observers, it seemed as though Abloh had made an unimaginable leap akin to a street-corner busker’s suddenly performing at Carnegie Hall — or, as Burke put it, that Abloh, a basketball fan, had awakened one morning to find that he’d become Michael Jordan. In hindsight, the spring 2019 menswear show was a fait accompli. It hadn’t gone off without a hitch. But it happened, and that was a marvel. “The tempo was slow. The guys didn’t know how to walk,” Burke said, as he offered his assessment of the day. “There were some things that were ill-fitting. I mean, there were all sorts of things. It was not a perfect show, but it was a perfect first show.”

The finale featured the usual promenade of models down the runway so that the audience could get one last look at the collection. As the last model passed, Abloh emerged from backstage to take his bows. Dressed in loose-fitting purple cargo pants and a black Louis Vuitton T-shirt, he walked down the runway with his hands clasped in front of him in a gesture of gratitude. When he spotted his friend West, Abloh pointed to him with affection. West stood, and the two men wrapped each other in a tearful embrace. It was more than a quick gesture of friendship; it was more emotional than the masculine ritual of affection that had two guys clasping hands and drawing each other in for a chest bump. Abloh and West held on to each other — two men who had been intertwined for a decade, each of them standing at the doorway to the fashion industry, West pounding on it with bravado and demanding entry, Abloh quietly knocking, unwilling to be shooed away.

“Kanye was the guy, when it was completely unpopular, that said, ‘I am not going to be typecast into a box.’ He willed it for us. That dream is just as much his as mine — in my dream, it was him down the runway,” Abloh said. “It actually wasn’t me on the runway; it was the community. That show was us.”

A thousand cameras clicked as the Louis Vuitton Don ceded his title. Abloh had achieved what West could not. As West later said, “Nobody owes me anything, but I’m still going to feel the way I feel.” Abloh’s accomplishment brought feelings of pride, envy, joy. He’d scored a win for everyone. That hug, not the clothes on the runway, was the image of the day. It circulated around the world.

Excerpted from Make It Ours: Crashing the Gates of Culture With Virgil Abloh, by Robin Givhan. Copyright 2025 by Robin Givhan. Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.